STORY #4

What the Edo Period teaches us About Sustainable Food

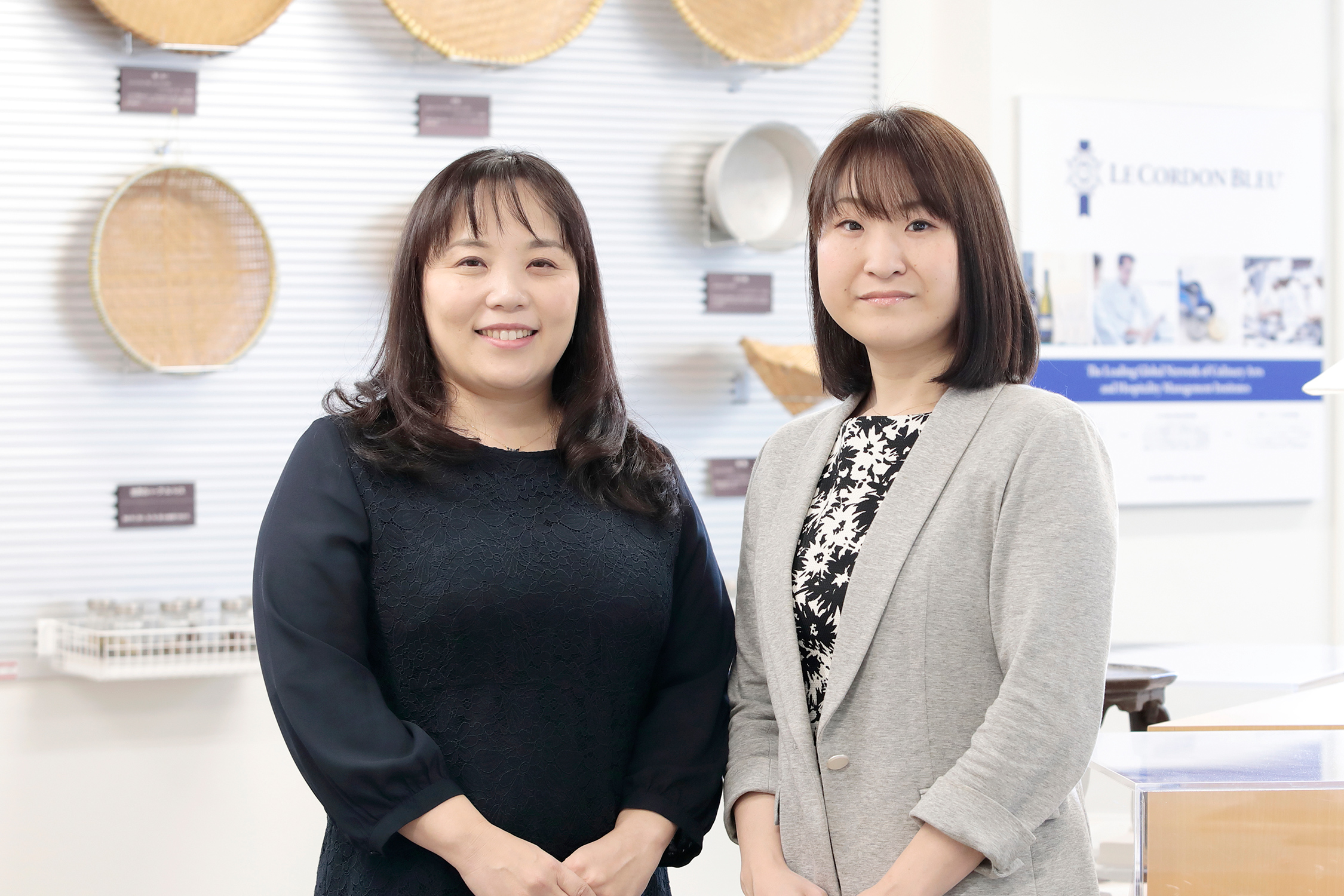

Kaoru Kamatani

Associate Professor, College of Gastronomy Management

Tomomi Nonaka

Associate Professor, College of Gastronomy Management

Photographs are provided by Group Photographer, Masahiro Takechi https://sshonpo.com/

Designing a sustainable future by unraveling history through historical studies and systems engineering.

One of the world’s largest festivals celebrating technology, music, and art, SXSW (South by Southwest), is to be held from March 13th to 22nd, 2020*, in Austin, Texas, United States. Ritsumeikan University’s Kaoru Kamatani and Tomomi Nonaka are planning to appear in a panel discussion at this big event where hundreds of thousands of people from approximately 100 nations are expected to gather.

The two plan to attend a user-generated session proposal platform called the Panelpicker. Themes are solicited from around the world, and theme-based speakers selected through online voting will join the discussion. From among several thousand entries, Kamatani and Nonaka’s Gastronomic Sciences Meet Edo Sustainability has garnered much attention.

“The reduction of waste, and the repurposing, recycling, and reuse of all kinds of items had taken root in the cities of the Edo period. All those centuries ago, a sustainable, recycling-oriented society had already been realized, not just environmentally, but also socially and economically. On the other hand, according to the United Nations, the total global population is soon expected to go beyond 9.7 billion, and this population cannot be sustained by the current rate of food production and supply. In considering the sustainability of food going forward, it was thought that there is much to learn, particularly from the urban society of the Edo period. As a researcher from Asia, I proposed this theme as I wished to discuss the future with researchers from the West, who are engaged in the fields of food technology and food innovation,” Nonaka explains.

While the Japanese phrase mottainai, which represents a sustainable way of thinking, has become globally known, Kamatani and Nonaka wish to share with the world the concept of chodo-ii (it’s just right) during their session. “When we, who live in the modern times, look at how people in the Edo period conducted their lives, trying to conserve food and recycling their clothes and other everyday items around them, they may appear to have a modest way of living while putting up with inconveniences. But it wasn’t that people back then strained to conserve. Rather, just like they used oil as a source of light because they had no electricity, perhaps all they were doing was simply using what they had to live a life that was just right. They lived life knowing what was sufficient and felt comfortable not going beyond their means. What we who live in the modern times should learn from the Edo period is perhaps the way they carried themselves,” Kamatani explains.

Nonaka and Kamatani co-hosted the event, The Kitchen Hacker’s Guide to the Food Galaxy in SXSW, at SXSW 2019, as a way to disseminate to the world a potential manner in which future food culture could be based on sustainability practices learned from the Edo period, Edo Sustainability: From Mottainai to Chodo-ii (It’s Just Right).

Kamatani and Nonaka wished to unravel history using food as their starting point and apply their learnings to future societal system designs. It was this that led them to jointly establish the EdoMirai Food System Design Lab in January 2019. The idea for Kamatani, whose expertise is in historical studies, and Nonaka, who conducts research in systems engineering, was to discover the history and culture of food rooted in the local Edo community, to convert this into valuable data from each of their perspectives, and to utilize that information towards creating a system design for a future society. In this lab, one of the first research projects they engaged in was to decipher a cookbook from the Edo period and reproduce it for the present age.

Their focus was a recipe book on Tofu dishes called Tofu Hyakuchin (100 Delicious Tofu Dishes), published in 1782. According to Kamatani, during the mid-Edo period, many cookbooks were published around the urban areas, and the Hyakuchin (100 Delicious Dishes) series, each book in which introduced 100 different ways of preparing a single ingredient, became popular. The two decided to try and recreate Fuwa Fuwa Dofu (Fluffy Tofu) and Tamago Dofu (Egg Tofu). However, when they translated the old document and reprinted it in modern language, they learned that they could not easily recreate those dishes as the quantity and amount of the ingredients, as well as the cooking methods, were ambiguous.

“In the case of the Fluffy Tofu, it is stated that we should ‘use the same amount of eggs and tofu,’ but it does not give us an idea of how many grams that would be, nor could we get a clear picture of what is meant by the terms like, ‘gently mix,’ ‘rub well together,’ or ‘boil.’”

Nonaka decided to interpret the recipe as a ‘design problem’ from a system engineering perspective and set the ‘fluffy state’ as the objective function while setting the mixing methods, strength of fire, heating duration, cooking equipment, and the like as the design function. She then actually prepared the dishes under a combination of various condition settings. This resulted in a range of dishes, some became plump like a Japanese style pancake, while others came out like crepes and yet another version turned out like scrambled eggs. In other words, depending on the conditions, each version came out differently in terms of both appearance and nutrients.

What caught Nonaka and Kamatani’s attention is the fact that incomplete information gave rise to a variety of dishes. “The vagueness of the recipe is what invokes the creativity and ingenuity of the cook. For example, the backdrop which gave rise to local cuisines that are unique to the region or how home cooking differs from one household to another must have been born out of such vagueness,” Nonaka analyzes. Kamatani points out that from the perspective of historical studies, “there is a lot to learn about the regional and historical diversity in the food culture that existed during the Edo period.” This led Nonaka to expand her perspective. She explains how the vagueness of information concerning recipes may be utilized in the process design of modern automated cooking devices or in robotic food preparations.

“In order to think about sustainability, it is vital to have a diversified perspective and a perspective that allows you to see through the past and into the future in various time-space axes,” they emphasize. What kind of future could be imagined when diverse knowledge starts to emerge from a union of two completely different approaches, one from a standpoint of historical studies, and the other from a standpoint of systems engineering? We eagerly anticipate the arrival of that future.

Fuwa Fuwa Dofu (Fluffy Tofu) recreated based on a recipe book from the Edo period titled Tofu Hyakuchin (100 Delicious Tofu Recipes). Many dishes were created because of the ambiguities in the recipes.

- Kaoru Kamatani (Photo Left)

- Associate Professor, College of Gastronomy Management

- Research Themes: Historical studies (Japanese history). The business history of early modern Japan, focusing on fisheries. Her recent focus of research is on agricultural productivity in early modern Japan and its relation to climate change, as well as on rethinking Japanese history through the medium of food.

- Specialties: Japanese history

- Tomomi Nonaka (Photo Right)

- Associate Professor, College of Gastronomy Management

- Research Themes: Sustainable social and business system design, Development of multi-purpose jelly food

- Specialties: Systems engineering, service engineering

- [Related information]

- EdoMirai

*The interview for the article was conducted in December 2019. Due to the spread of the novel coronavirus, SXSW (South by Southwest) 2020 was canceled.