STORY #7

Japanese Migrants Fishing in Pre-war Canada

Norifumi Kawahara

Professor, College of Letters

Elucidating the realities of the work and lifestyles of Japanese people lived in Canada from a “Large-scale map”

For Japan, surrounded as it is by ocean, fish have always been one of the most important sources of food. Looking back at the history of the fisheries that have long supported the dietary needs of the Japanese population, it is known that before the Second World War, a large number of people traveled across the seas in search of work and a place to call home. While studies and reports are abundant in terms of agricultural immigrants who moved to Hawaii and North and South America, details on fishing-immigrants are rather scarce, as are the actual number of studies. But Norifumi Kawahara is shedding a light upon such fishing-immigrants—who have remained to a great extent unknown. What is especially noteworthy is the fact that Kawahara defined the realities of life and work of Japanese fishermen through an approach to historical geography based on—for example—fire insurance plans.

Collection and delivery ship carrying salmon to a cannery. A weighing machine can be seen at the stern (left side of the picture).

Photographs: Takasaki Family Collection (Ibusuki, Kagoshima Prefecture)

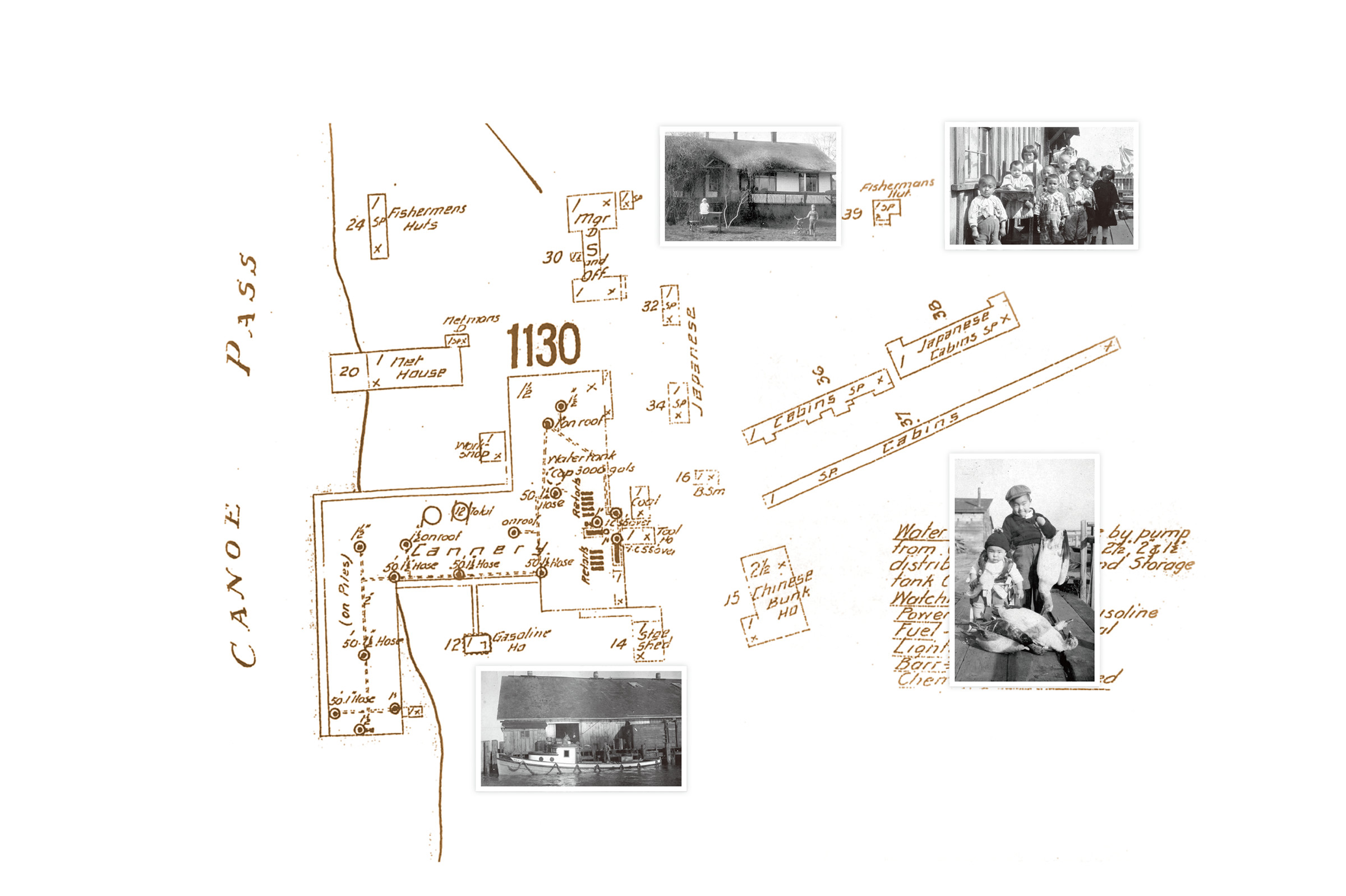

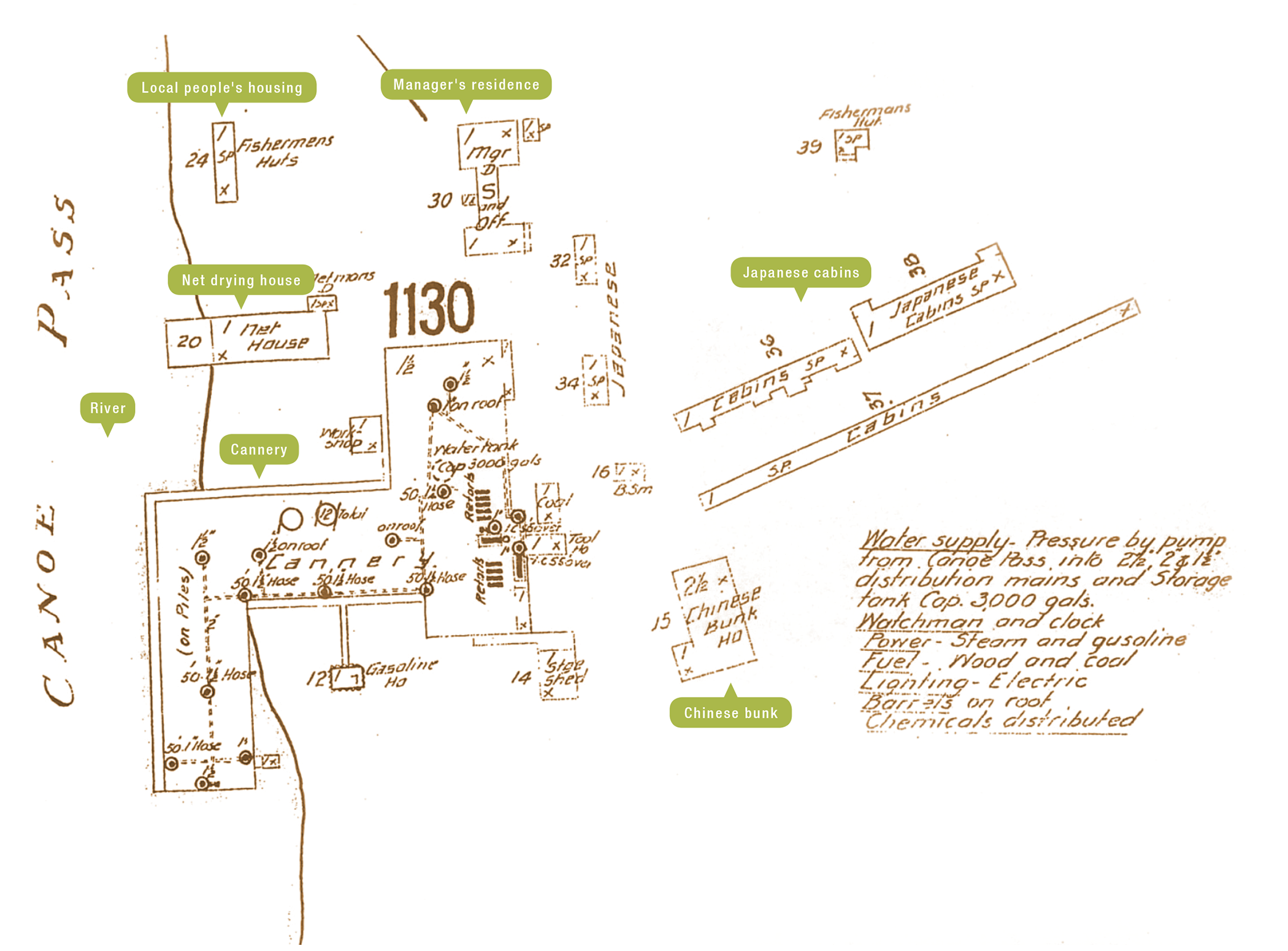

According to Kawahara, fire insurance plans are in fact large-scale maps that insurance companies use to assess the risk of fires associated with factories and facilities in neighborhoods to manage insurance claims following a fire. These maps have been issued since the late 19th century in England, America, Canada, and other countries. Kawahara carefully analyzed the maps and identified very interesting facts about the Japanese migrants to Canada around 1920.

An interesting example is the presence of migrant fishermen who worked in the salmon canning industry in British Colombia (BC), in Canada. Looking at fire insurance plans in the 1920s, there were about one hundred salmon canning factories (canneries) located along the BC coast, close to Steveston at the mouth of the Fraser River. They were run by British Canadians, who employed many Europeans, Japanese, and Chinese, in addition to a number of locals. “An interesting thing is that the labor was divided such that Japanese caught the salmon, Chinese canned them, while the locals provided supplementary labor,” explains Kawahara.

Kawahara confirmed that at the same time, canneries to the north of BC very rarely had any Chinese workers. Instead, Europeans monopolized the most important roles, while Japanese and local people were responsible for both fishing and canning operations—illustrating significant regional differences in the system in terms of division of labor.

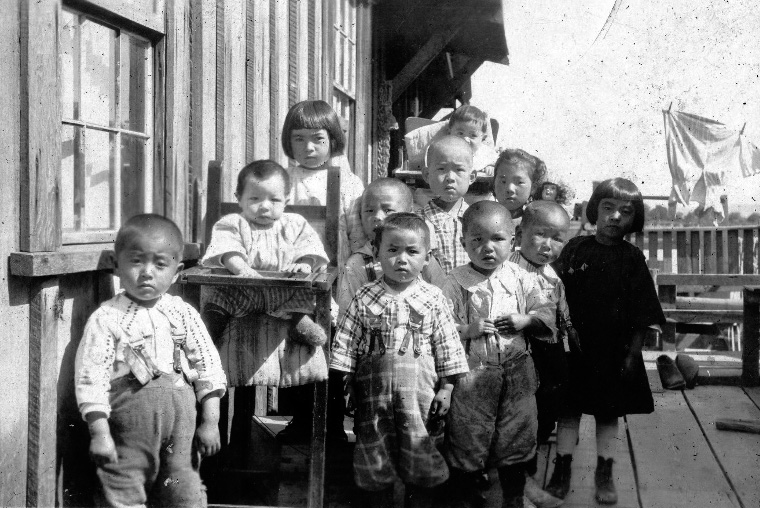

Following this, Kawahara worked out the family structures based on the housing conditions. “Referring to fire insurance plans and photographs from those times, it can be clearly seen that there were multiple forms of worker residences adjacent to the canneries. Chinese people lived in lodgings which were known as ‘Chinese bunks.’ At the canneries, Chinese men often worked away from their families, living in bunkhouses in which double bunks were arranged. The houses where the Japanese lived were known as ‘Japanese Cabins,’ and it is apparent that these dwellings comprised independent or row houses—albeit very simplistic ones. This was because many fishing migrants from Japan lived with their wives and children in family units. In addition, locals mostly lived in ‘huts.’”

Fire insurance plan of Brunswick cannery at Canoe Pass (1923)

Photographs: Takasaki Family Collection (Ibusuki, Kagoshima Prefecture)

Manager's residence

Children belonging to a cannery gather at a Japanese cabin

Salmon collection/delivery ship docking at a cannery

Kawahara also attracts attention by discussing the roles of workers from Kagoshima Prefecture, which until that point had been largely ignored. What really interests him is that the people from Kagoshima Prefecture—whose work had nothing to do with fishing—became involved in the salmon canning industry in northern BC.

“People from southern Kagoshima Prefecture initially went to Canada as contract immigrants to work in mining or railroad maintenance, but as this work was very hard and dangerous, many of them turned to the salmon canning industry at the termination of their three-year contracts,” Kawahara surmises. “However, southern BC already had immigrants from Wakayama Prefecture who were highly skilled in the fishery industry, so they were probably forced to work for small but relatively new canneries in places other than Steveston, such as the Brunswick Cannery or even in canneries in the north.”

Kawahara is also expanding the scope of his research to fisheries other than salmon. One of these is whaling, which involves the extraction of whale oil; and he has again shown that Japanese played an important role in the dismembering of whales.

Another topic Kawahara has looked into is the Japanese engaged in the herring processing business. Canadian fisheries didn't attach the same level of importance to herrings as they did salmon, and the herring industry was monopolized by Japanese fishermen for a period in the 1920s and 1930s. Perusing documents such as “Kaigai niokeru Honpoujin no Gyogyojokyo (The Situation of Japanese Fisheries Overseas)” and “Kanada-Taiheiyo-Gan Nishin Ohirame Gyogyochosahokoku (Fishery Survey Reports on Herrings and Halibuts on the Pacific Coast of Canada),” by the then-Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce during a fact-finding survey of second generation Japanese immigrants involved in herring fisheries, Kawahara uncovered many precious facts. “Japanese fishermen in Canada caught herrings coming into the Strait of Georgia and established a global distribution network that exported them to Japan and Japanese colonies such as Korea and Taiwan,” a smiling Kawahara explains. “It’s so interesting to follow such dynamic movements that were unique to fishing migrants in the Pacific region.”

Children of a salmon collector/deliverer, the Takasaki family

- Norifumi Kawahara

- Professor, College of Letters

- Subjects of Research: Geographical study concerning the migration and job changes of fishermen in the present day

- Research Keywords: Historical geography, study of Canadian-Japanese immigrants