STORY #4

Deciphering the Words of a Heretic Group of Christianity to Understand its Unknown Doctrine

Yutaka Arita

Associate Professor, College of Policy Science

Mapping the History of the Waldenses: Charting the Path of this Rare Group of Christianity from the Medieval Times to the Present Day

There is a group of Christianity called the Waldenses, which originated in medieval Europe. The group exists to this day, despite being denounced as “heretics” by the Catholic church not long after they were formed. The Waldenses are hardly known in Japan; however, Yutaka Arita is globally renowned as a leading Japanese researcher on the Waldenses.

According to Arita, the Waldenses were formed in the late 12th century in Lyon, France, as a group of Christianity whose teachings originated with and were propagated among the common people. They were denounced as “heretics” in 1184 but continued their activities underground for a long time. In 1532, during the era of Reformation, they doctrinally merged with the Reformed Church (the Calvinists). But, despite all this activity, they maintained their name and organization as the “Waldenses” for over 800 years. So how, while most other such Heretic groups have disappeared from history, have the Waldenses survived to this day, even though they were, at points, deemed heretics and either ostracized or merged with other denominations? Arita thought that “perhaps the identity of the Waldenses was based on something other than their doctrine”. Beginning with this thought, he attempted to answer the big question, “Who are the Waldenses?”

Arita’s approach is unique: he attempts to elucidate the reality of the Waldenses from the perspective of believers. “What makes heresiology hard,” he says, “is the difficulty of locating historical documents written by those who were declared heretics, because of persecution and book-burning. Therefore, in such studies, there is little choice but to reference documents written from the perspective of the Catholic church. However, in the case of the Waldenses, there is quite a bit of literature from the believers’ points of view, ranging from writings from the Middle Ages to those from modern times. I am trying to understand the Waldenses from their own perspective by unraveling the contents of their literature.”

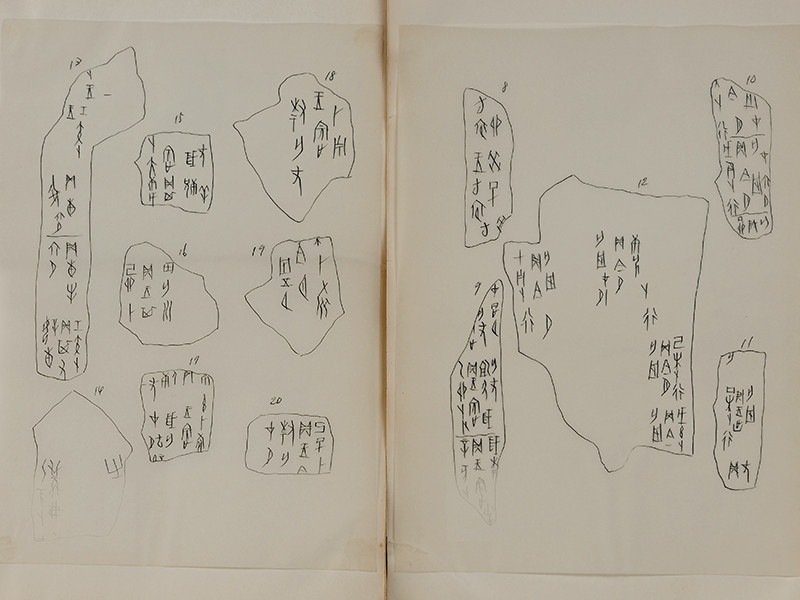

This process of deciphering the contents is not easy. Many medieval documents are written in archaic languages that are no longer in use, and the Waldenses changed the common language of use in their community several times throughout history. Nevertheless, Arita diachronically chronicled the languages that the Waldenses used through the centuries.

The burning of a female Waldensian (From Jean Leger’s Histoire generale des églises évangeliques de Piémont ou Vaudoises, 1669)

The symbol of the Waldensian Church, LUX LUCET IN TENEBRIS.

The symbol is derived from a sentence in the Gospel according to John 1:5 “The light shines in the darkness”, which means Waldenses is like a candlestick that can bring “the light of the gospel”.

“The Waldenses have used approximately six languages over time. First, they used the Old Provençal language during the 12th and 13th Centuries. Valdo, the founder of the group, is said to have translated the Bible from Latin into this language; it was commonly used in Lyon, where he lived at that time. From the 13th to 16th centuries, the Waldenses focused on expanding their congregation, and a number of translated Bibles, doctrines and historical books were compiled for religious education and missionary work across Europe. These are written in Old Occitan, and Latin is only found in letters to external religious reformers.”

The greatest turning point in the historical journey of the Waldenses was the Reformation in the 16th century. The Waldenses joined the Reformation movement in French-speaking Switzerland. As they became more aligned with Protestantism, they began using French, and French became the official language of the Waldensian church. Today, French remains their primary official language. In the 19th century, Italian was chosen to be their secondary official language to enable easy evangelism in Italy. At the same time, a small group of believers moved to Spanish-speaking Uruguay in South America, and Spanish became the Waldensian church’s tertiary official language.

“What is interesting is that, in Europe, there is a Waldensian community that uses languages other than French,” continues Arita. Between the 13th and 14th centuries, some Waldenses, who were living in Piedmont valley, moved to the Calabrian region of southern Italy to establish new towns. One of these towns was called the Guardia Piemontese. This settlement is far from Piedmont, but their common language is still Occitan, which they call “Piemontese (Piedmont dialect).” It is fascinating how the geographical resettlement of the group several centuries ago continues to inform the language of the present community there.

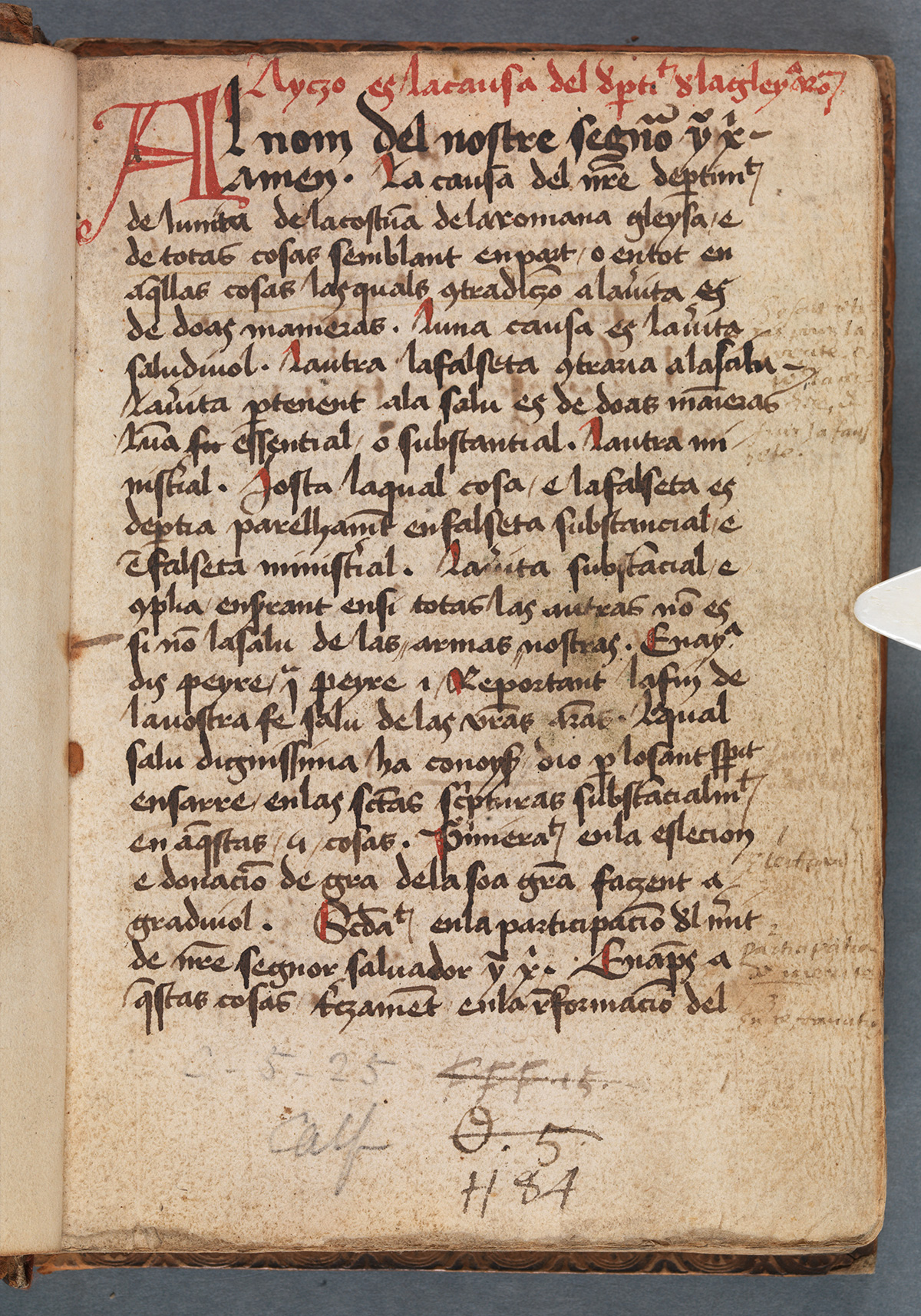

“This is the cause of our department of the Roman Church”

Ayczo es la causa del nostre departiment de la gleysa romana(Mss.C.5.25., Trinity College Library of Dublin)

One of the medieval Waldensian documents. Author unknown. Written in the Old Occitan (Lingua Valdese). There is only one surviving manuscript, and it is said to have been established around the beginning of the 16th century. The manuscript is composed of two parts; in the first half is written the Statement of Faith, and criticisms toward the Catholic Church is in the latter half. The manuscript has not been revised, so the specific content remains unknown to date.

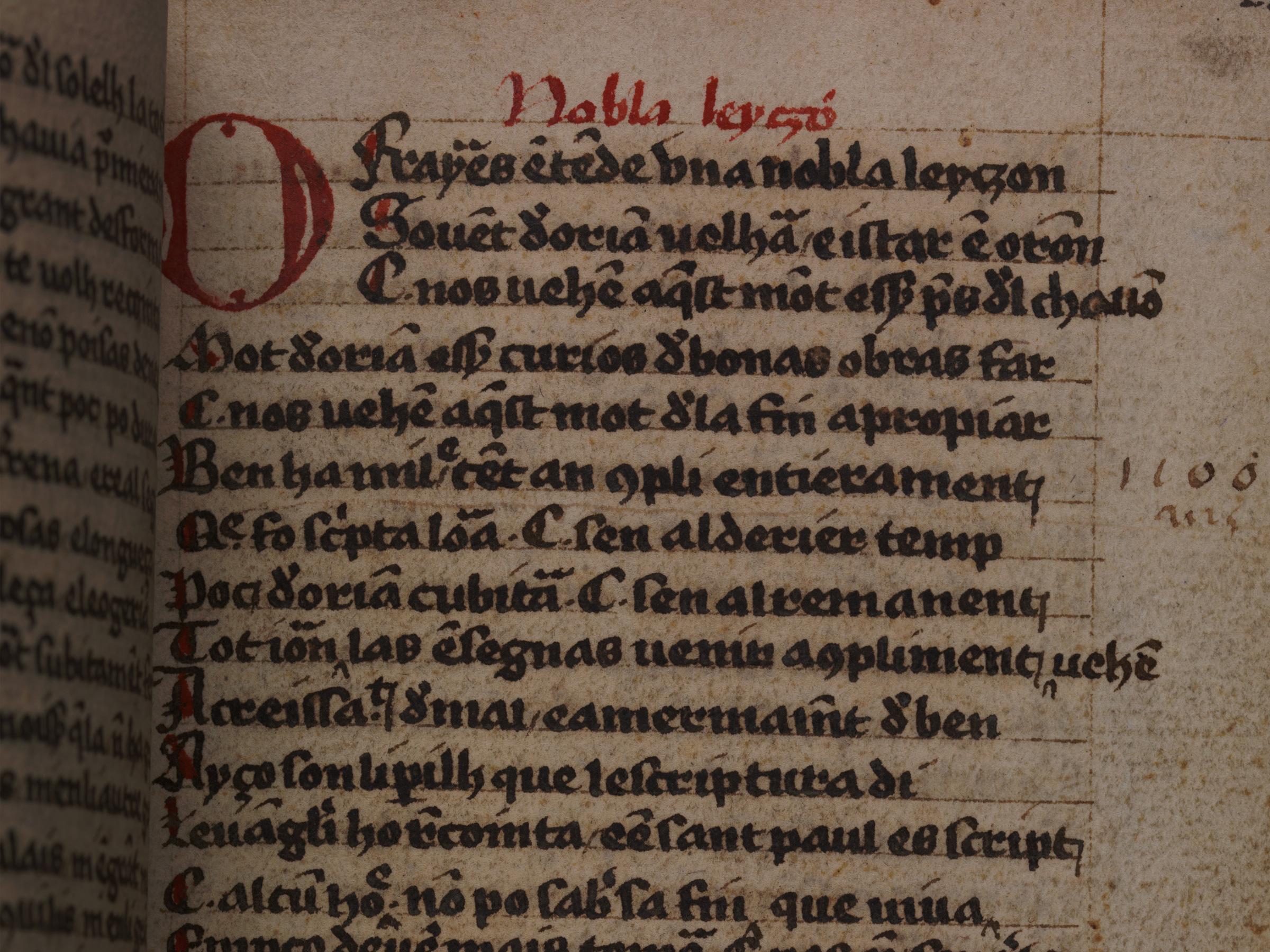

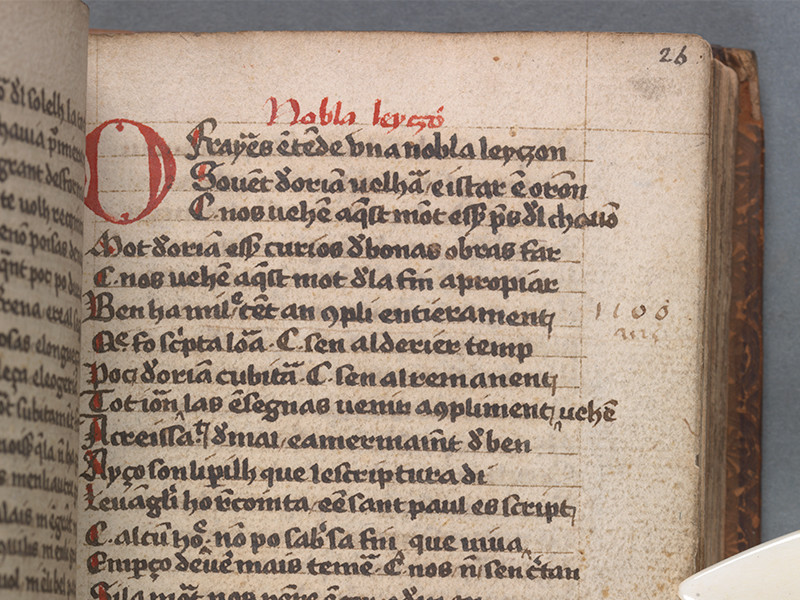

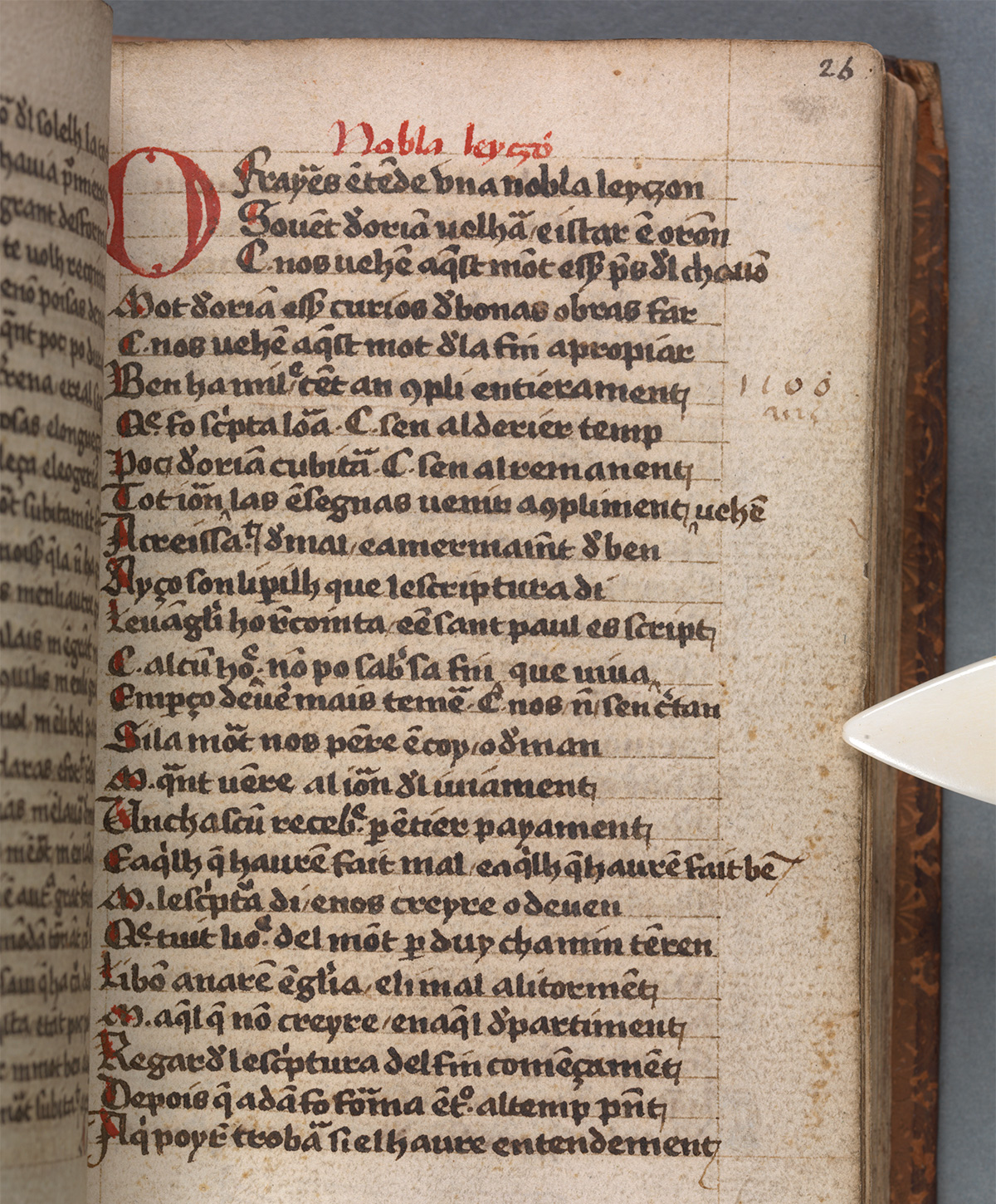

Arita, having perused and analyzed many Waldensian documents, which have been passed down over generations and are written in Old Occitan, Latin, French, and Italian, translated a Waldensian document, one of their most major and famous accomplishments, to Japanese. The document is called La Nobla Leyczon (The Noble Lesson). It comprises one of eight psalms written by the Waldenses themselves during the Middle Ages. This psalm is said to have been established around the 1420s and contains their doctrines. Arita’s translation of La Nobla Leyczon is the oldest of four extant copies of Waldensian manuscripts and is written in rhyme on parchment.

One of the difficulties of translating the document was that it was written in a language known as the Lingua Valdese (Waldensian language). “Lingua Valdese is a variant or dialect of the Old Occitan used in the Piedmont valley of the Alpine region where the Waldenses lived during the 15th century. Many medieval Waldensian documents are written in this language,” Arita explains. The language is no longer in use and there are no dictionaries in which the exact definitions of the words of the language can be found. Arita had no option but to use his knowledge and understanding of the various European languages to painstakingly translate the document word for word.

“Several things came to light upon my analysis of La Nobla Leyczon. One was its covert criticism of the “orthodox” Catholic church. It became clear that the medieval Waldenses saw themselves as persecuted saints and the proper and legitimate successors to the apostles.” Arita also noticed several errors in their interpretation of the Bible. “One of the characteristics of the Waldenses is the extreme importance they give to the Bible. So, what led them to misinterpret it? There is no end to my interest,” says Arita.

Arita’s research of the psalms that the Waldenses wrote several hundred years ago may bring to light the unknown doctrine of the medieval Waldenses.

La Nobla Leyczon (Mss.C.5.21., Trinity College Library of Dublin)

One of the eight medieval Waldensian psalms; author unknown. There are four extant copies of the manuscript, which was written around the 15th or 16th century. In its 492 lines are Waldensian views on the apocalypse described in the Book of Revelation, an overview of the portion of the Bible that deals with the history, records of teachings and actions of Jesus Christ, and criticism of the Catholic church. The manuscript seems to have been created to help Waldenses gain basic religious knowledge as preachers and has doctrinal features.

- Yutaka Arita

- Associate Professor, College of Policy Science

- Research Themes: The history of the Waldenses

- Specialties: European literature

- [Related information]

Japanese Association for Waldensian Studies