STORY #1

Why do most automated voice

guidance systems use a

female voice?

Kenji Sakata, Ph.D.

Professor, College of Social Sciences

The intriguing

relationship between

the social history of voice,

voice media, and gender

We are surrounded by voice prompts and guidance. The automatic checkout lines in supermarkets and convenience stores instruct us, saying, “Please select your payment method” and “Please take your change and receipt.” In Japan, roadways undergoing repair warn the drivers, “Please be careful as the roads are narrow.” When the bath is heated to the preset temperature, an automatic voice prompt is heard from a machine telling us that our bath is ready. Error messages in automatic ticket gates in train stations, announcements in trains and facilities, voice prompts in car navigation systems, voice assistance functions on smartphones—the list is inexhaustible.

“Why are most of these machines using female voices?” asks Professor Kenji Sakata, the College of Social Sciences. Sakata focuses on this strong and deeply rooted relationship between voice and gender, a subject that has received little attention. “The ‘voice’ is clearly taking on a gender-like role, and it is embedded in our society as if that was something normal all along. Therefore, there must be some hitherto unknown gender bias behind this choice,” he speculates. Why, when, and in what way did it become embedded into society and turned self-evident? Sakata is trying to unravel the links between voice and gender that exist in society and highlight the gender issues lurking in the background.

Sakata has made “the social history of voice” his main theme throughout his academic career. He focuses on cabled broadcasting, wired broadcasting, telephone, street advertisements, and various other “audio media” formats, exploring their meaning and significance from a historical and sociological perspective.

As a premise for his research, by going over accumulated research, newspaper articles, historical materials, and other literature, Sakata has identified when the female voice became the primary actor in the voice media.

For example, he explains the early days of the telephone, a prime example of voice media, as its use became widespread in the society. “Back then, calls could be connected only via telephone operators, and in the United States, working-class boys in their teens predominantly performed this role.” However, they lacked the finesse in communicating with bourgeois entrepreneurs and clients. That is why young middle-class women replaced these boys, who were more polished and trained to take on a supportive role, such as that of a secretary or a household servant. When the telephone service was launched in Japan in 1890 (Meiji 23), the operators were also primarily men. However, that role was gradually replaced by women. “The reason behind this change had to do with the unique Japanese values that saw women as holding an ancillary role to men,” says Sakata. Continuing with this convention, to this day, even though the role of a telephone operator no longer exists, voice media such as the telephone has a strong gender preference for women, speculates Sakata.

Sakata also mentions another aspect of social history relating to the telephone as a medium. When the telephone first became popular, it had another function besides its use for conversations— as a wired broadcasting system, it was used to disseminate information. According to Sakata, once commercial radio appeared in the market in the United States in 1920, the telephone as a broadcasting medium was gradually replaced by the radio. Subsequently, households became the target of a new sales channel. “It was during this time that the telephone companies started associating a new value to the telephone, which is to use the telephone as a means to ‘freely enjoy conversations.’ When we analyze the telephone companies’ advertisements in the 1920s in the United States, we find completely different messages than the previous corporation-focused ads. They were advocating people to ‘call your relatives and friends who live far away.’ Appearing in those ads were housewives, the women who were stereotyped as people ‘who like to talk’,” observes Sakata. He believes this may have formed the backdrop for linking telephones with females and with a particular gender.

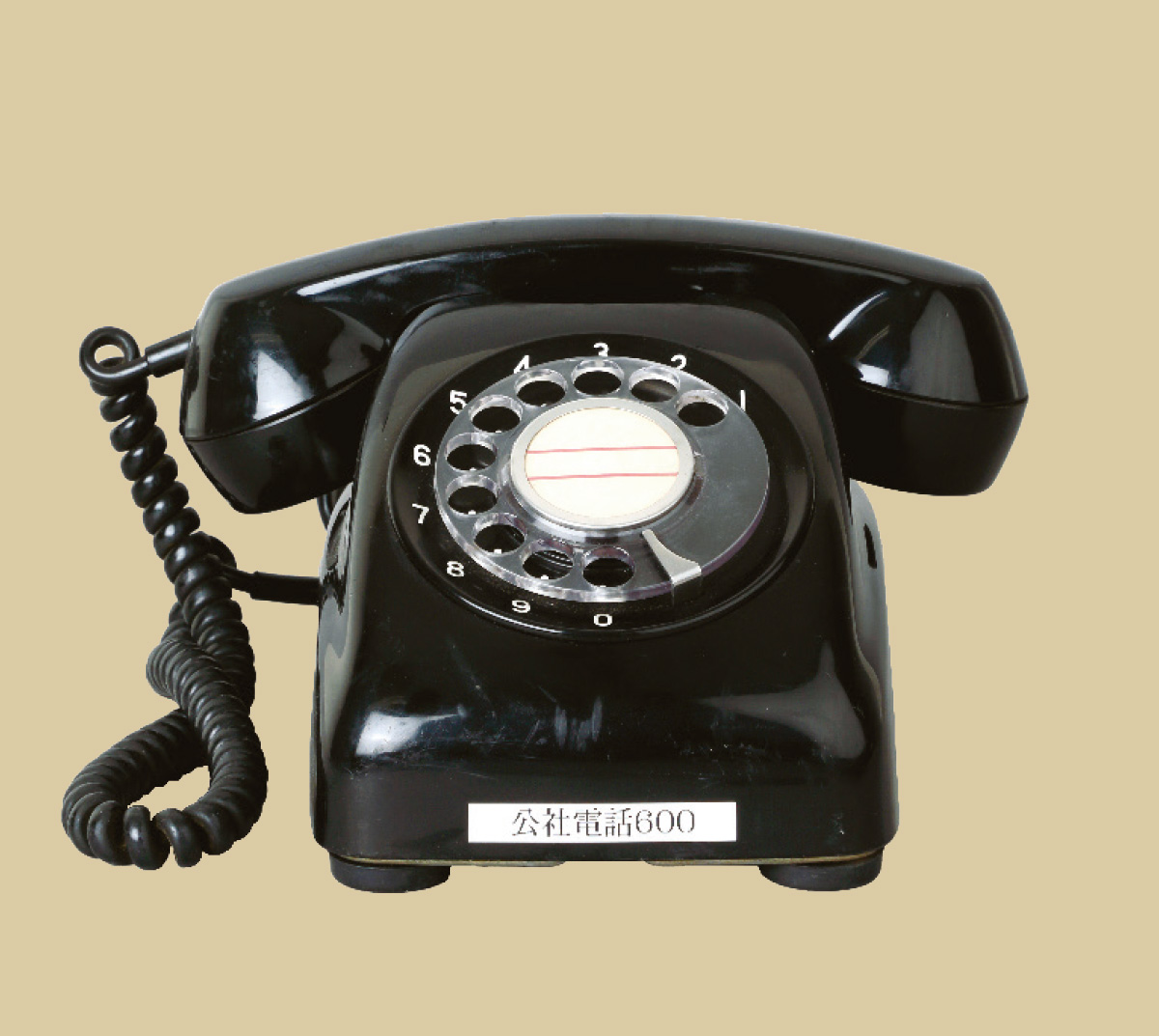

Sakata’s telephone collection. These wired broadcasting telephones were gifts and donations from those involved in his research in various capacities. Many public-corporation black telephone devices were protected by covers and treated with care as valuable objects since they were borrowed from the public corporation (i.e. the state). These covers alone signify the relationship between the telephone and the people in society.

Fast forward to the present day. AI assistants, as voice media, are becoming rapidly popular. The default setting in these media is to use female voices, as evidenced by Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa. “Of course, it is possible to switch them to male voices. Nonetheless, most users do not bother to switch and keep the feminine voice,” says Sakata. Such female voices in these “ancillary roles” continue to increase unconsciously and steadily with the advancement of technology. Sakata warns of the danger of continuing with this trend without concern for associating ‘female voices’ with these fixed gender roles, as they could lead to stereotyping and consolidating such gender perceptions.

“A report released by the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) in 2019 notes that ‘AI voice assistants are promoting sexism’,” says Sakata. He is attempting to discover the relationship between the “voice” as an entity with no physical presence and gender bias that is ubiquitous in our daily lives by clarifying this historical flow and elucidating why and when this happened through the lens of social history.

There are countless gender studies, but none focus on the connection between the “voice” and “gender” from a historical perspective. Sakata expresses with conviction that this is exactly how his research offers a novel perspective and why it holds social significance.

- Kenji Sakata, Ph.D.

- Professor, College of Social Sciences

- Specialty: Sociology

- Research Themes: Social History of Audio Media; Digging up History of Region’s Unique Voice Media; Utilization of Local Radio in Intergenerational Communication; Points of Contact Between Local Community and Radio; Points of Contact of Memory Sharing and Local Radio