Memory and attention

This material covers week 6 of the course.

Note that this material is subject to ongoing refinements and updates!

Overview

This theme covers human memory and attention.

Human memory

Traditionally, short-term and long-term memory were seen as distinct storage systems in the brain. However, recent research suggests a more interconnected view.

Short-term memory

Short-term memory, often referred to as working memory, is not a separate storage area but a dynamic process of attention. It involves the brain focusing on a small subset of currently active neural patterns. These patterns can stem from ongoing perceptions or retrieved long-term memories. Basically, short-term memory is what we are consciously aware of at a given moment.

Brain damage studies support this model. Impairments can affect either the ability to focus attention (using our short-term memory) or the storage and retrieval of long-term memories, depending on the damaged area.

Our short-term memory has a rather low capacity:

"The low capacity of short-term memory is fairly well known. Many college-educated people have read about 'the magical number seven, plus or minus two', proposed by cognitive psychologist George Miller in 1956 as the limit on the number of simultaneous unrelated items in human short-term memory" (Johnson, 2021, p. 82).

Short-term memory is volatile–we’ve all had experiences where an interruption means we forgot what we were talking about, or forgetting why we went into another room.

Common questions about short-term memory:

- "What are the items in short-term memory? They are current perceptions and retrieved memories. They are goals, numbers, words, names, sounds, images, odours—anything one can be aware of.

- Why must items be unrelated? Because if two items are related, they correspond to one big neural activity pattern—one set of features—and hence one item, not two.

- Why the fudge-factor of plus or minus two? Because researchers cannot measure with perfect accuracy how much people can recall, and because of differences between individuals in how much they can remember" (Johnson, 2021, p. 83).

Designing for short-term memory

Short-term memory implications for user interface design

- Use modes - For example, a digital camera in video mode will start recording video when the "take photo" button is pressed, whereas in photo modes like auto, shutter priority or aperture priority, the same button will take a photo. Similarly, dragging on the canvas of a graphics app will have a different result depending on whether you have, say, the text mode or the draw shape mode selected. The problem with this type of interaction is that users can forget which mode they're in.

- Search results. One of the problems with search is that by the time users have reviewed the results from their search, they've already forgotten what the search terms they entered were. A tangible solution to this is to keep the search terms viewable while users review the results (Google now does this).

- Instructions. If someone gave you a long list of verbal instructions of how to get to a particular location, or how to make a particular dish, it's unlikely you'd remember them. Such complicated procedures are best communicated in writing, stored somewhere where they're easily retrieved. Therefore, any complicated procedures in software need to be clearly available to the user.

Long-term memory

Long-term memory is formed through changes in neural connections, strengthened by repeated activation. It's not localised but distributed across our brain networks:

"Memory formation consists of long-lasting and even permanent changes in the neurons involved in a neural activity pattern, which make the pattern easier to reactivate in the future... Activating a memory consists of reactivating the same pattern of neural activity that occurred when the memory was formed" (Johnson, 2021, pp. 80-81)

Long-term memory, which, unlike short-term memory, is an actual memory store, has several limitations:

- It is error prone

- It's weighted by emotions

- Retroactively alterable (Our recollection of events can change over time).

More focus on goals, less on tools to achieve them

However, as the reading notes, humans have long had tools to augment long-term memory, such as notebooks, checklists, journals, calendars, and so on. At the very least though, apps should avoid being a burden on users’ long-term memory. Note that such tools are secondary to our goals. We simply see them as a means for achieving something.

We focus on information relevant to our goals

External aids help us manage our short-term memory in a number of ways

- Counting objects - using markers or containers when counting large numbers of objects

- Bookmarks to show where we’re up to in a book

- Doing arithmetic on paper or with a calculator

- Writing checklists

- Document management - separating edited and to-be-edited documents.

"Focusing our attention on our goals makes us interpret what we see on a display or hear in a telephone menu in a very literal way. People don’t think deeply about instructions, command names, option labels, icons, navigation bar items, or any other aspect of the user interface of computer-based tools. If the goal in their head is to make a flight reservation, their attention will be attracted by anything displaying the words 'buy', 'flight', 'ticket', or 'reservation'" (Johnson, 2021, p. 99).

We prefer the familiar, and this has implications for the design of systems:

- Sometimes "mindlessness trumps keystrokes" (in other words, we don't think when using simple software such as an ATM)

- Guide your users to the most efficient paths

- Help more experienced users speed up processes

Goal, execute, evaluate

We have a thought cycle of goal, execute, and evaluate, relevant to a range of activities. In a design context, we need to consider these steps in the following way:

- "Goal: Provide clear paths—including initial steps—for the user goals that the software is intended to support.

- Execute: Software concepts (objects and actions) should be based on the task rather than the implementation. Don’t force users to figure out how the software’s objects and actions map to those of the task. Provide clear information scent at choice points to guide users to their goals. Don’t make them choose actions that seem to take them away from their goal in order to achieve it.

- Evaluate: Provide feedback and status information to show users their progress toward the goal. Allow users to back out of tasks that didn’t take them toward their goal" (Johnson, 2021, p. 105).

Short-term memory, however, often leads to lapses in completing task-ending steps due to attentional shift and resource limitations. It's important that software remind users of any remaining steps required (such as logging out after completing a task).

Recognition and recall

What do recognition and recall mean? According to Johnson:

"Activating a memory consists of reactivating the same pattern of neural activity that occurred when the memory was formed. Somehow the brain distinguishes initial activations of neural patterns from reactivations—perhaps by measuring the relative ease with which the pattern was reactivated. New perceptions very similar to the original ones reactivate the same patterns of neurons, resulting in recognition if the reactivated perception reaches awareness.

In the absence of a similar perception, stimulation from activity in other parts of the brain can also reactivate a pattern of neural activity, which if it reaches awareness results in recall" (2021, p. 81)

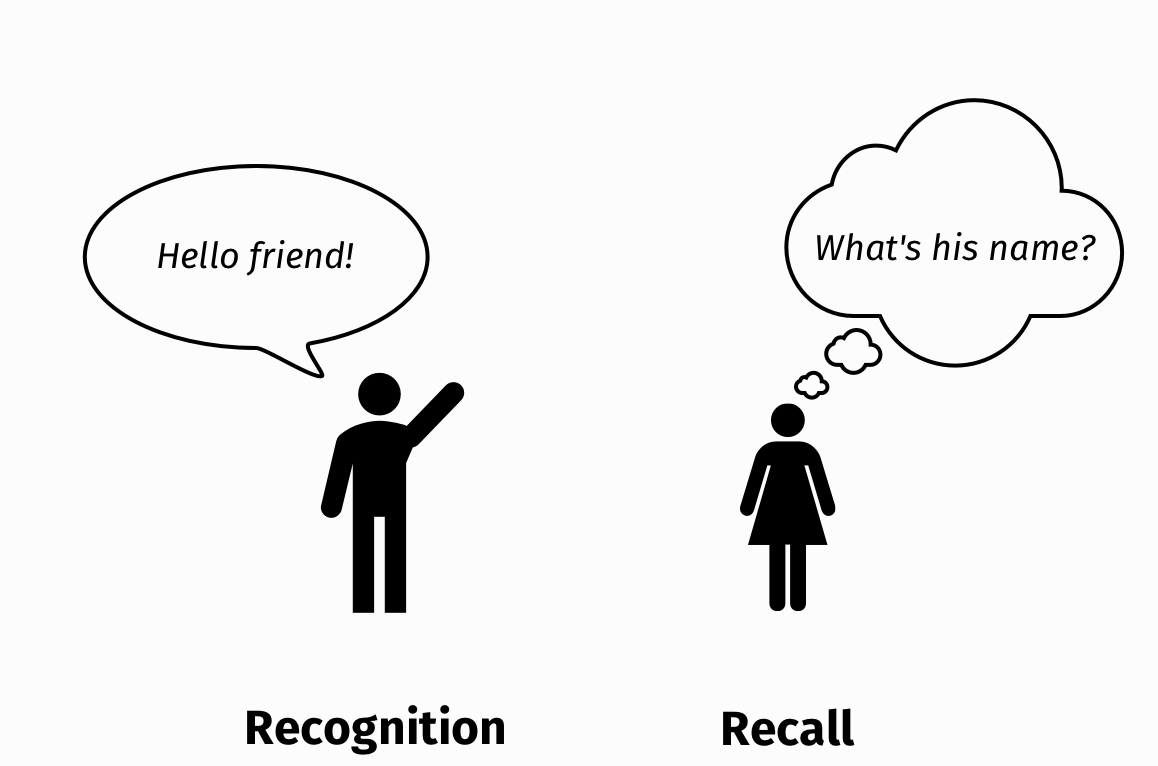

In more simplified terms, recognition is the ability to identify something as familiar - for example, recognising a sound, face, or word, that one has encountered before. Recall, on the other hand, is the ability to retrieve a piece of information without any external cues - for example, recalling a phone number or a particular fact.

This figure might help illustrate the difference between the two:

Figure: A familiar example of recoginition vs recall

Recognition

- Humans excel at recognition due to evolutionary pressures.

- Recognition is based on reactivating existing neural patterns triggered by similar perceptions.

- Facial recognition is exceptionally fast due to direct pattern matching.

Recall

- Recall is more challenging as it requires reactivating patterns without strong perceptual cues.

- The brain is not optimised for recalling isolated facts.

- Humans rely on external aids like writing and technology to enhance memory — we "outsource" a lot of our cognition.

- Ancient memory techniques involved mental visualisation.

- Modern methods primarily involve external storage and reminders.

- Electronic aids, especially those with reminders, are particularly effective.

Recognition versus recall

A few key differences between the two:

- Recogntion is based on cues, while recall has minimal cues.

- Recall requires more cognitive effort.

- Not only is recognition easier than recall, it is more accurate.

Implications for user interface design

- See and choose is easier than recall and type

- Use pictures where possible to convey function.

- Use thumbnail images to depict full-sized images compactly

- The larger the number of people who will use a function, the more visible the function should be

- Use visual cues to let users recognise where they are

- Make authentication information easy to recall

Back to top | © Paul Haimes at Ritsumeikan University | View template on Github