STORY #4

The Story of a Professional Archivist Who Collaborates with Worldwide Museum Curators

The digital images used in the title belong to Art Research Center Collection, Ritsumeikan University: arcHS03-0008-4, arcUP3437, arcUP1605, eik3-1-04, arcSP01-0123, arcKG00565, arcKG00227, arcMD01-0714, sakBK02-0013, sakBK02-0015, eik2-1-80, eik2-1-80, arcFS00-0001A, arcBK03-0134-02, hayBK02-0050-03-05

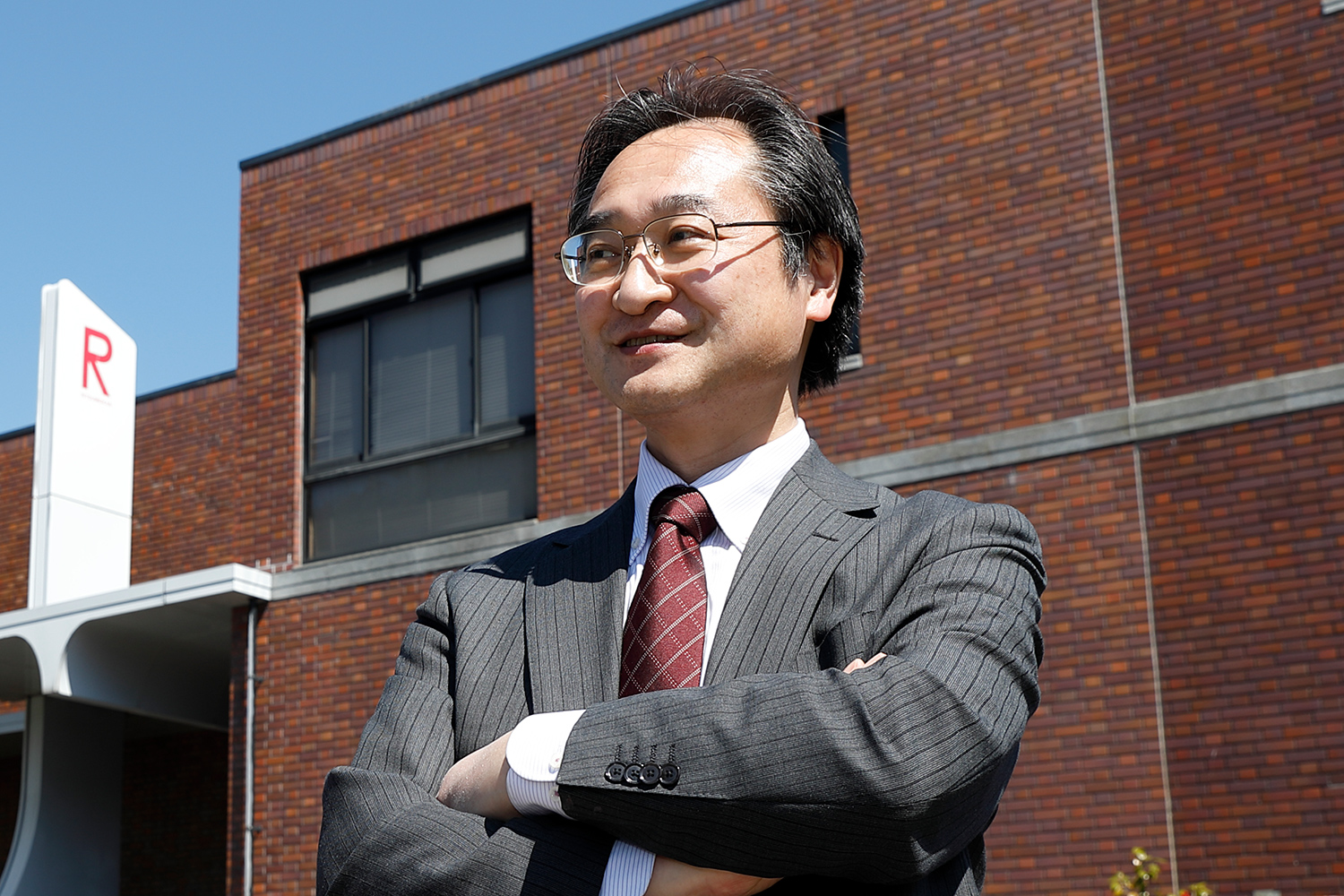

Ryo Akama

Professor, College of Letters

Have you ever visited online art museums? These are unique facilities where you can access on your smartphones or laptop computers, thousands of artworks from museums, some of which are too fragile or too expensive to be opened to public. This allows not just the museums’ curators or visitors, but indeed, a global audience, to benefit from high-resolution photo archives of the museum’s collection. “Online web museums are a good example of how digitalized data archives can be used, but it is not the only one,” remarks Ryo Akama, Director of the Art Research Center at the Ritsumeikan University.

Akama, a pioneer of digital archiving, defines digital archives as cultural resources prepared and structured according to the predicted future use. “It is not just a digital ‘grab bag’ into which digitalized photos or videos are randomly pushed,” Akama explains. He goes on to emphasize the importance of strategizing archiving, focusing on how and for what the data might be used later. “Once the strategy becomes clear, we can decide the methods of digitalization, such as digital photos, videos, and sound recording. Human imagination is limited, and we are clueless about the future of digital interface, sometimes making revision of strategies necessary, but a lack of clear strategy while recording your collections will result in a messy and short-lasting archive.”

Akama recalls the day he first got involved in archiving and building databases in late 1980s, when ‘digital archiving,’ a word that first came into use in 1994, was still unheard of. He was then working at Waseda University, at the Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum, which commemorates the novelist and drama researcher Shoyo Tsubouchi, famous for his Japanese translations of Shakespeare. The museum is devoted to drama history, and owns more than forty-five thousand ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblock prints collected mainly by Tsubouchi, who recognized the value of the then-neglected and dispersed ukiyo-e unique records of performing arts that cannot be seen in any other country. “I wanted to organize this collection,” says Akama, “and so I started by taking photos of the printings, developed the films in service size, and filed them in binders. I did not completely realize what I was doing, since archiving was not a popular concept then. I was just hoping that by filing photos, I could always study the ukiyo-e without entering the museum storage.”

With over 10,000 ukiyo-e prints in its possession, the Art Research Center (ARC) holds one of the most preeminent collections in Japan. While there are numerous prints from the end of the Edo Period to the Meiji Period such as those by Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, and many of the prints portray kabuki actors (yakusha-e), one of the themes for the collection is Kyoto itself, and ARC holds the world’s largest collection of prints of noted places (meisho-e) in Kyoto. Furthermore, the collection includes Kappazuri—stenciled ukiyo-e prints produced without the use of woodblocks, which was a particular printing method developed around Kyoto and Osaka area—and yakusha-e related to kabuki performances held in Kyoto.

Another subject area within the ukiyo-e collection of ARC is that relating to Chūshingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers), a fictionalized retelling of a historical event that has ceaselessly inspired Japanese art and drama. ARC holds one of the top three collections of prints relating to Chūshingura.

In addition, the rare and valuable picture scrolls, Katagami (paper stencils) for Kimono dyeing, and classic books and magazines relating to both art and theater, have grown to Japan’s leading collections.

Simply taking pictures of cultural resources such as those of historical literature and ukiyo-e prints using a digital camera is not sufficient when creating a digital archive as it involves multiple procedures. Photographing resources with severe degradation or insect damages is impossible without first going through a restoration process, and even if one were to digitalize such materials despite the damages, they would not prove to be satisfactory data. At ARC, such materials undergo careful restoration processes by its skilled restorers before they are digitized, and only after thorough quality reviews the rendered images are published and made available to the users.

After moving to Ritsumeikan University, Akama started his new digital-type project of scanning another private collection, that of stage photos. “There were around one hundred and thirty thousand unorganized photos, and I took on part-time student workers to help me complete scanning. I had them work in three shifts, and they scanned 24 hours a day with 6 scanners. I told them to scan everything in the collection to avoid wasting time selecting, which can be done after scanning is completed,” Akama remembers.

This scanning project was successfully completed, and this experience enabled Akama to scan all ukiyo-e printings he had once photographed. By the end of 1999, he built a searchable database consisting of image files with titles and short descriptions at the Art Research Center, which was established in 1998 at the Kinugasa campus as a research hub integrating liberal arts and science by utilizing digital tools to study Japanese art and culture and promote integrated research projects.

The database was released to public in 2001 on a server belonging to Waseda University. What frustrated Akama before the release was a copyright problem. “I believed at that time that the database would not have infringed anyone's copyright as long as Waseda University publicized their collection on their own server. However, there were certain stakeholders who feared that digital publication might have reduced the worth of original artworks, and thus the value of the University's property.” Since nobody was willing to decide whether or not to publicize the database, Akama released it himself, only to be praised by researchers from outside that the archive was remarkable. “It was a drastic measure, but it worked. Nobody blamed me as they soon understood that the database did not ruin the value of the artworks, but rather the opposite,” he smiles.

In 2002, Akama went on a sabbatical leave from Ritsumeikan University and visited England. There, he started a collaboration project at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “I worked with a curator who is in charge of archiving their ukiyo-e collection comprising about thirty eight thousand printings,” Akama recalls. “I digitized them all in 2 years using a digital camera, and added those visuals to the Art Research Center’s database. Encouraged by this collaboration, other museums and universities in England began to seek collaborations with us. One of them was the British Museum.”

The know-how of digital photography is also a skill that was cultivated over long years of experience and research, providing high-quality images at a high-speed while making sure they are digitized safely in a manner that does not cause damage to the materials. The shooting equipment is configured to be light-weight, so that they can be brought overseas easily. It is because they have mastered both the restoration and shooting techniques that they can draw out new information and appeal as cultural resources inherent in such materials.

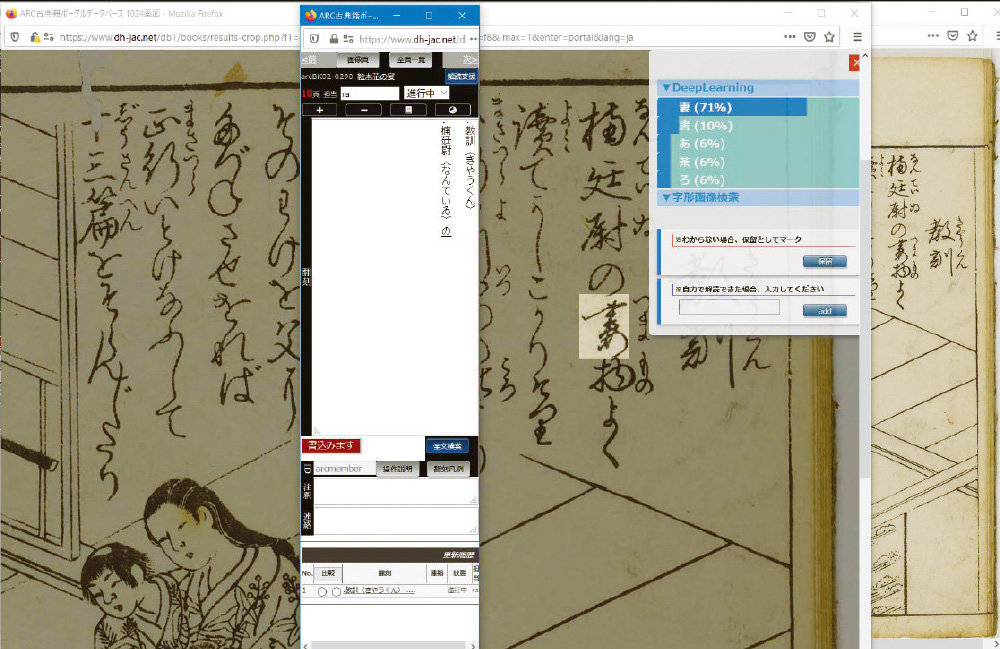

Since the digitalized materials are registered into the database and can be easily viewed online, the user can also work on deciphering the materials online. For this reason, various interconnected supportive systems are made available to the user. This figure shows how the ancient text from a classic book is converted into legible text by the Kuzushiji (cursive characters) Character Recognition support system using AI.

Akama and the curators of the British Museum worked with a professor from the SOAS University in London to digitalize their ukiyo-e collection. The personal relationships built through this collaboration later enabled them to organize exhibitions on ukiyo-e, and the photos taken were utilized to make exhibition catalogs and souvenirs. This experience helped Akama realize that digitalization of artworks will enable not only curators but also other stakeholders to contribute to related projects like exhibition or catalog designing.

In recent years, Akama has started to take his students with him to collaborating museums to help them acquire skills related to archiving museum collections. “Strategy, as I mentioned earlier, is a key to learn for digitalization. What’s more, digitalizing means more than just taking photos. We must not damage materials while handling them. If the materials have been already damaged, we might even have to propose a method to repair them. The students in my lab are trained to be professionals who will be relied upon by museum curators for their skills and knowledge,” guarantees Akama.

Akama elaborates that digital archives have several advantages for both collection holders and database users. The holders can organize their collections well, and make them easily available for external researchers and art enthusiasts, some of whom may potentially initiate collaborations that add value to what they store. The site viewers can enjoy them in web museums away from crowded exhibition halls to selectively observe what they prefer, or review them after they visit the physical exhibitions, just as they read the catalogs they purchase.

“It is beneficial in fields of education as well,” Akama continues. “For example, we developed an AI-supported education system to teach how to read classic Japanese documents or books written in cursive handwriting. Cursive handwritings sometimes have different shapes from present letters, and until a while ago, lecturers had to reprint them in person to enable their students to read them. With our system developed in collaboration with Toppan Printing Co., Ltd., students can try reprinting by themselves with hints provided by AI based on archives of thousands of pages of classic printings.”

In another educational project, Akama had his students curate art materials online and design their own web museum. However, he has to admit that even he is sometimes surprised by others who are good at designing new schemes to utilize the database. “One such developer was a distinguished American programmer named John Risig,” says Akama, “who was a big fan of ukiyo-e and made a portal “Ukiyo-e Search,” on which visitors can search across multiple museum collections for similar printings. Using his portal, we can find different printings printed from the same printing block.”

Akama is now focusing on shedding light on art materials that has received little attention. “I would like have them rediscovered with new value or new meaning. We have archived not just the famous artworks but also hundreds of thousands of materials by obscure printmakers. One such work has even been chosen by a Taiwanese whisky distillery as a label design for their new merchandise. The work, which had been unfamiliar to Japanese, became famous in Taiwan. I believe other works have much potential as well.”

“The COVID-19 outbreak has led us

to a more online-based lifestyle,

and higher incoming demand for the use of digital archives than ever before.”

In 2019, Akama and the Art Research Center successfully purchased a series of paper scrolls that had barely survived in Belgium from plundering during World War II. The series, “Shuten-doji emaki”, which illustrates a heroic legend of a group of samurais who subjugated a mystical leader of Japanese demons, Shuten-doji, had been written and drawn around 1650s, and collected by an American art collector W. Bigelow, whose collection forms a prominent part of the Japan Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The series later moved to Belgium after Bigelow gave them to one of his friends to commemorate his daughter’s wedding to a Belgian politician.

Since the paper and painting have been severely damaged, Akama opened an online crowdfunding project aiming to repair the series and digitalize them to open them to public. Having raised more budget than he had been expected, he is now working on repairing them and creating an online digital exhibition as well as a real exhibition, using digital archives. He has in his mind a new dream to collaborate with researchers of not just Japanese literature and history but also informatics and business, who are interested in cultural resources.

He concludes that he is now welcoming ideas from young stakeholders on how to utilize archived materials including these resources.

All five volumes of “The Tale of Shuten Doji,” which have returned to its place of origin.

“Before and after images of the restoration of the fourth volume.” Created circa 1650.

The activities of ARC have also extended to calling valuable pieces that had left the country back to Japan. This picture scroll used to be part of the famous William Sturgis Bigelow Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It had left the U.S. to Europe, and now it has become part of the collection held at ARC. Since this picture scroll had been enjoyed by many overseas for a long time, degradation has progressed. Thus, led by Prof. Akama, a repair and restoration project has begun. Crowdfunding has been used to secure funding, and this effort has also led to wide publicization of the existence of this scroll. While the target for the completion of the picture scroll’s restoration is the year 2024, an early exhibition on Shuten Doji has also been planned for 2023 to put the completed volumes on display.

- Ryo Akama

- Professor, College of Letters

- Research Themes: Japanese theater, information culturology, Japanese art Specialties: Cultural assets study and museology, aesthetics and studies on art, Japanese literature

*The interview for the article was conducted in March 2020.