STORY #2

Invitation to Fieldwork

Nina Takashino, Ph.D.

Associate Professor, College of Policy Science

Face-to-face interview surveys

for improving lives

of people in poverty

As the saying goes, seeing is believing. If you want to know what life is like in a different country or culture, going there yourself is and always has been a good way to find it out.

Nina Takashino studies social capital generation and gender empowerment of people in poverty and has conducted fieldwork in several countries, including Indonesia and Bangladesh, to learn about people’s lives and the challenges they face. As Associate Professor of Community and Regional Policy Studies (CRPS) major at the College of Policy Science at Ritsumeikan University, Takashino is currently seeking students to participate in her research projects. CRPS major is an undergraduate degree program where students can study policy science in English. Many of the students are from Asia, but Japanese students are, of course, welcome. The department is characterized by its emphasis on fieldwork and on-site experience rather than classroom learning.

If you have no previous fieldwork experience, it may be difficult to imagine what kind of a study process it is. With Takashino, let us take a look at an example of how fieldwork proceeds from its preparation to completion.

Preparation is the key to successful research. Once you decide which country you want to visit and what theme you want to focus on, the first step is finding a counterpart for the field research. “Counterparts are the people who act as liaisons between us and the people in actual study sites,” explains Takashino. “We ask them to adopt the survey tools we send from Japan and translate the survey questionnaires prepared in Japanese into local languages. What is particularly difficult for the Japanese alone are to recruit people in slums (or villages in poverty) to cooperate with the survey and to hire survey assistants to help us on-site. Since the counterparts play such important roles in the field, conducting surveys without them would be very difficult, if not impossible.”

For their counterpart, Takashino and her team search for a university professor they know in the area; even if the professor cannot participate, they may ask them to introduce them to other researchers or local NGOs. “There are organizations with contracts with donors such as international aid agencies and governments to reduce poverty or to solve local problems, and we can ask them whether they are interested in our topic,” Takashino explains. There is a case that a government employee came to Ritsumeikan University as a working international student to learn research methods, and his organization played his study counterpart. On the other hand, research assistants are often recruited from students at counterpart universities and work as interviewers with the subjects.

Takashino and her team emphasize face-to-face interviews with local residents, for example, those living in slums. The counterpart negotiates with the leader of the slum prior to the arrival of the Japanese team to enlist the residents who can cooperate in the interviews. In parallel with the on-site preparation by the counterpart, the Japanese team need to prepare a questionnaire for the interviews. Of course it depends on the survey theme; however, questionnaires are usually about eight A4 pages for an hour-long interview. Some of the questions are on demographics of the interviewee such as age group, education, and marital status.

Survey in India; the seated student is a survey assistant.

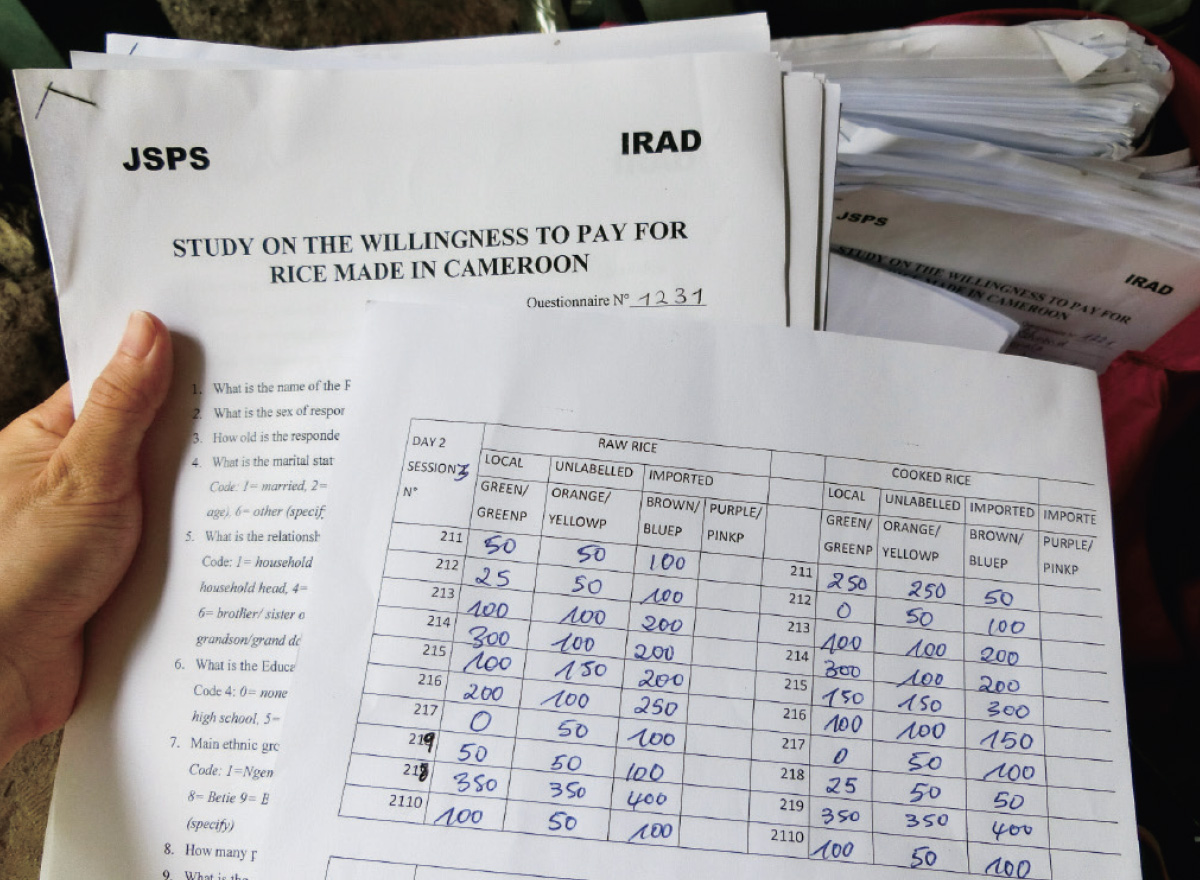

The questionnaire used in Cameroon.The research assistant conducts the interview in the local language and fills in the form in English.

The study in Cameroon used an experimental method of purchasing rice.

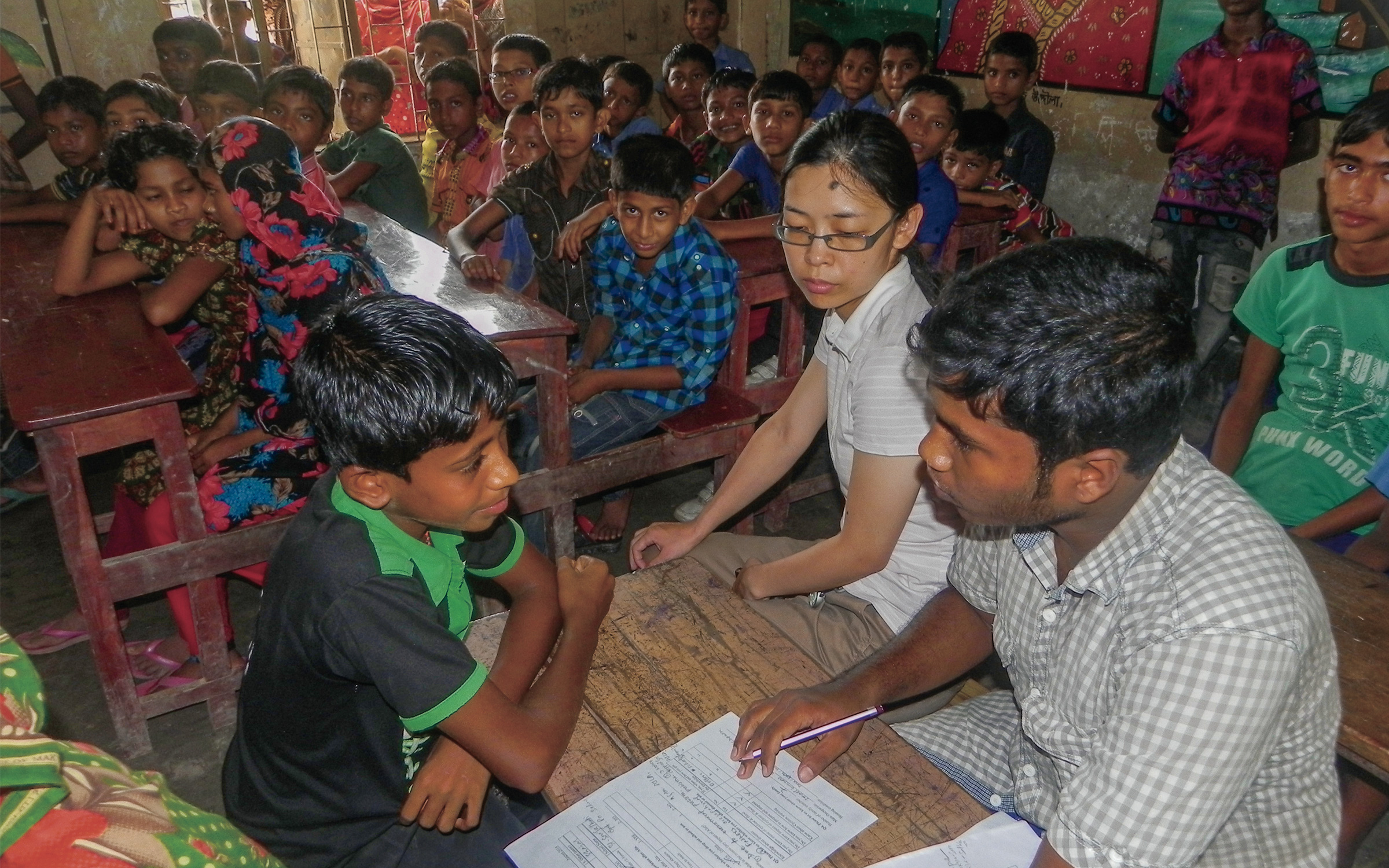

Study in a cyclone-affected area in coastal Bangladesh. Surveys are rare and attract a lot of onlookers.

Takashino provides some tips to make a questionnaire useful and reliable. “First, be careful not to use open-ended questions like ‘What are you struggling with?’ because it tends to be difficult to analyze the answers to such questions numerically. It is better to ask, ‘How troubling do you find this problem?’ and provide a scale, like 5 (very troubling) and 1 (not troubling at all).” The second tip is to not ask delicate questions too soon. “An interviewee may at first be wary of an interviewer who meets them for the first time and tries to ask about their personal life,” she explains. “There are some surveys that go to the same village yearly to take continuous data (panel data) for multiple years, which makes it easier to gain the villagers’ trust. However, in many cases, the survey is conducted only once. Taking data from hundreds of subjects makes it difficult to meet one person repeatedly to build a good relationship. Still, they can become accustomed to the interview process as it progresses, so it is a good idea to position questions that are difficult to ask later in the questionnaire.”

At a survey on disaster prevention education at an elementary school in Bangladesh. Many roads and bridges in Bangladesh were built with aid from Japan, and therefore the country is friendly to Japan. When Takashino entered the classroom, all the children stood up and welcomed her with "As-salamu alaikum! (Hello!)"

You may be asking yourself, “why do they need a questionnaire for a face-to-face interview survey?” Takashino explains that since many slum dwellers are illiterate, the research assistants need to read the questions to them while listening to their answers and writing them on the questionnaire sheets. One of the most important preparations is to train the research assistants in advance so that they can understand what the team wants to learn and communicate with the subjects in accordance with the research purposes.

Once the questionnaire is completed, the data are sent to the counterpart for translation and data entry. Takashino admits that the paper-based questionnaire can be heavy and bulky, and she even had a bitter experience of having the luggage containing the filled-out forms stolen. She is willing to use digital tools such as tablets to store data in the cloud, and she tried that once, but the communication and data synchronization was unreliable and it did not go well.

After a lengthy preparation process that may take several months, the survey begins. The actual contact with the local people is made by research assistants, but the Japanese team members also visit the slum to oversee the interviews. What the team observed was that no matter how good the questions they prepare and how hard their research assistants work, they can never have all people state their opinion candidly. For example, in a survey on domestic harassment, a woman who answered “nothing” to the question “Do you have any problems?” could not stop crying during the whole interview. She probably could not say anything because she was afraid of her situation might worsen if her husband or relatives found out about her discussing her situation. There is a reality that cannot be observed simply by waiting for the survey results.

A Bangladeshi child catching small fish.

A Cameroonian vegetable seller.

Bangladeshi girls offering their hands.

Takashino first became interested in poverty issues in developing countries when she was in junior-high school and was exposed to reports of child prostitution in Cambodia. Her father explained to his shocked daughter that there were people who were deprived of their human rights and dignity because of poverty, and about the United Nations as an institution responsible for solving global social, economic, and humanitarian problems. “I studied economics in college and international cooperation in graduate school, and it was not until I worked as a teaching assistant for international students that I began to see education as a career,” Takashino recalls. “I thought that a university would be a better fit for me, where I could learn about the region through research and nurture leaders who could work there, rather than becoming a UN official to help the region by myself.”

One advantage of a university is that it can provide human and monetary resources to work with small NGOs and other organizations that would have difficulty conducting large-scale research on their own. Takashino stresses that it is not always easy to make relationships with small-scale partners sustainable. “We ask those NGOs to send us quotes before starting preparations, but it is sometimes too high and we have to decline some of their purchasing requests.” The gratuities paid to slum leaders can also be problematic. Takashino tries to keep the amount that takes into account the general income level of the area, but some leaders are accustomed to cooperating with surveys and may negotiate a higher amount. She cannot pay the amount of gratuities paid in large-scale surveys conducted by the United Nations and other organizations out of her survey budget.

Despite these hardships, Takashino emphasized that the joy of watching students gain experience and learn things they did not know is irreplaceable. Japanese students often have a hard time when they visit developing countries for the first time, becoming ill or being surprised by the unhygienic toilets. However, one student, who had obtained a passport for the first time to attend the fieldwork class, chose to go to India on his own for an internship after returning from the field work, while another found employment with development consulting firms that support the local community. Although it is difficult to immediately link the research results to improvements in local societies, Takashino and her team have been developing human resources in the long run to improve the lives of the people in poverty in the region. “In my lab, I don’t tell the students the research themes they should work on. I am willing to help students pursue their themes. For example, I am planning to work with a government-sponsored student coming to Japan from Bangladesh, who is scheduled to come in the fall, on the role of women in improving agricultural productivity. If you are hesitant to get involved because you don’t have any experience or skills, don’t worry! The only requirement to join our team is whether you have a passion for making someone’s life better.”

Bangladeshi children carrying fruits.

A rice shop in Cameroon selling imported rice.

Lunch during the Cameroon survey.

Bangladeshi children showing off their red henna tattoos.

Indonesian farmer's cow.

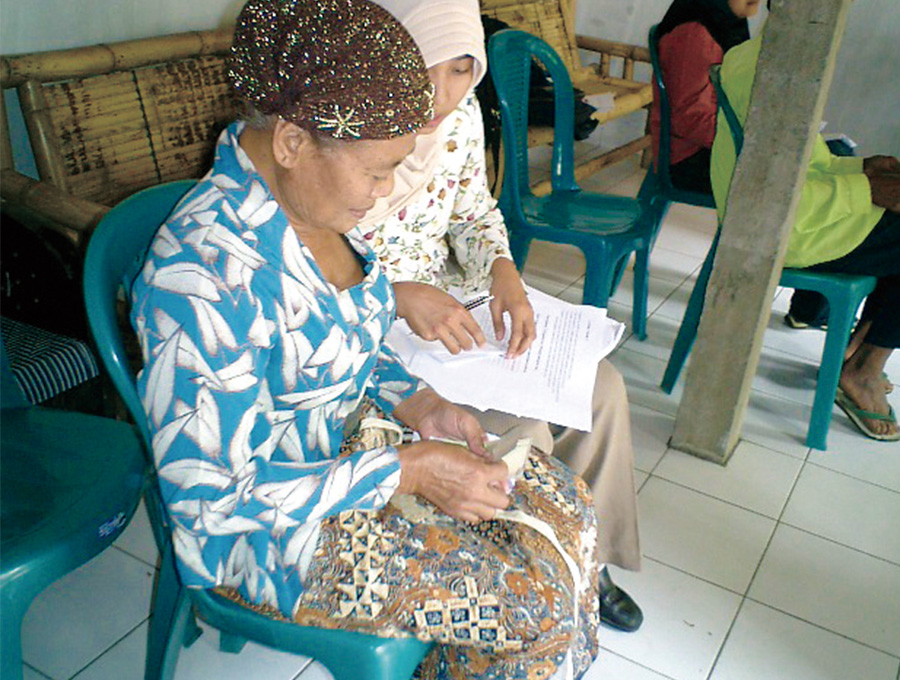

Interviews conducted in Indonesia.

A survey on consumer evaluation of domestic rice in Cameroon. An investigation to explore the feasibility of domestic rice production due to the transformation of dietary habits from traditional potatoes, bananas, etc. to rice, mainly in urban areas.

- Nina Takashino, Ph.D.

- Associate Professor, College of Policy Science

- Specialties: Development economics, agricultural economics, gender studies

- Research Themes: Development, gender empowerment and human security