STORY #1-1

From hardware and software

to the pleasure of playing

Koichi Hosoi, Ph.D.

Professor, College of Image Arts and Sciences

Game Archive Project aiming

to preserve game culture

Since the early days of the discipline, when it was still unclear what and how to study, Koichi Hosoi has been searching for a way to research games. Ritsumeikan University Game Archive Project, to which Hosoi has devoted many years, is one answer to the question.

When Hosoi first came up with the idea of game research, there was almost no research material. “I personally owned some titles, but there were too few of them to do anything worthwhile. Then I tried to buy some more with research funds, but I was admonished and told to not buy toys with the university research budget,” Hosoi recalls. The situation changed for the better when he met Masayuki Uemura, the Head of the Nintendo Research and Development 2 (as it was previously called). With Uemura’s assistance, Nintendo decided to lend Hosoi’s team about 1,800 NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) software, which had been stored in-house, so that it could be organized and classified. The team checked basic information of each game such as title, release date, and manufacturer on the package, title screen, and even on the end roll after playing it in person and published the information on the project's website. Although they started from the only thing they could do at that time, it turned out to be an epoch-making initiative in that it regarded games as cultural assets and tools for future human resource development and established a system for public use.

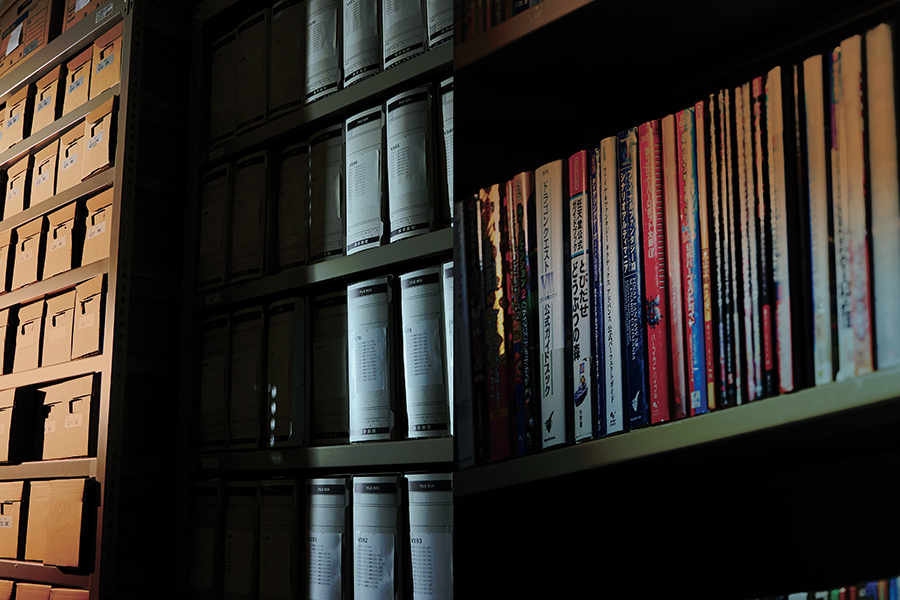

As of February 2022, 11,283 software titles, 115 types of hardware, 200 types of peripherals, and about 8,000 types of related materials such as magazines, flyers, newspaper advertisements, soundtracks, etc. (excluding duplicates) have been registered in the archive, and the actual materials are stored at the University at 24 degrees Celsius and 50% humidity in accordance with the standards of the Library of Congress in the United States. The current number of hardware and software in the University's collection is the largest among the public institutions in Japan, including the National Diet Library, and one of the largest in the world. This data is also officially provided to the Media Arts Database built by the Agency for Cultural Affairs.

However, no matter how much the storage environment is prepared, eventual deterioration of hardware and software is inevitable. It should ideally be maintained and managed in a state where it can be played at any time, but Hosoi is concerned about the lack of technology and funding that may affect maintenance and dynamic preservation. “When I visited our partners in Europe and the United States, I found they had plenty of private donations and public subsidies, and the funds raised were used to cover the cost of dynamic preservation and make conservation activities sustainable,” Hosoi recalls. The Japanese government has recently revised the Museum Act, allowing universities and other research institutions to register museums. “Universities have a variety of materials, but the ecosystem for maintaining and publishing them in a state where they can be used permanently is not well established. Games are difficult to handle because of their complex intellectual rights involved, but I believe we should build a new model for social use and establish a system to pass on the value and meaning of games.”

RCGS has planned several research exhibitions to introduce the materials in its collection and to consider how it should exhibit them in the future. The game music exhibition “Ludo-Musica II,” which was held online until February 2022, was the second project with the theme of game music and was well received partly due to the topicality of the use of game music at the opening ceremony of the Summer Olympics in 2021. “It was one of the projects we implemented with support from the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and although it was not sustainable, the knowhow of the exhibitions cannot be accumulated unless we actually plan and experience them. We learned a lot this time as well, such as what kind of negotiations are necessary with whom to clear the intellectual rights-related issues, how and for whom to write commentaries of the exhibition, etc. Our goal is to make these exhibitions possible on our own or through industry-academia collaboration rather than with subsidies, and to create a circular archive that balances the maintenance and management of collections and cultural resources with an environment where faculty members and students can research and learn.”

“Research Exhibition: The Life and Times of TV Game PART ONE-Showa Era”: Reflections on the era up to 1986, when video games were introduced to Japan and became popular. Reproduced the gameplay scene back in 1986.

If we think of games as interactive entertainment created by humans playing them, rather than just objects, we also need to preserve for future generations information on how people play and what they find interesting. Hosoi says that archives of traditional performing arts such as Kabuki and Jōruri (Japanese puppet show) from the Edo period can be used as a reference. “It is impossible to relive the show from the past through video records, of course, but we can glean a wealth of information about the situation at that time from ukiyo-e prints, scripts, dialogue extracts, song collections, and guidebooks called gekisho, which contain actors’ reviews or autobiographies. As for games, it is also necessary to organize not only hardware and software, but also printed media such as game magazines, strategy books, doujinshi (fanzines), and advertising materials for future reference.”

According to Hosoi, several other projects have already been launched, such as the automatic collection of basic information on non-console games such as online games and social games, and the collection of oral histories of game developers and businesspeople. While he admits that many of these activities will take time, it is hoped that the Game Archive Projects will continue to grow, aiming to preserve not only physical materials, but also the culture surrounding games.

- Koichi Hosoi, Ph.D.

- Professor, College of Image Arts and Sciences

- Research Themes: Making and Social Utilization of Game Archives as Cultural Resource; Market structure and its historical development in the Contents Industry (Creative Industries); Establishment of a Japanese culture research environment utilizing a metaverse (virtual space)

- Specialties: Cultural Resource Management Studies; Library and Information Science