Research Relating to Copyrights and

Intellectual Property Rights

of Digital Games

In 1982, the plaintiffs prevailed in a court case in which the makers of a game, commonly known as Invader Game, had sued the manufacturers of pirated copies. Back then, Invader Game was all the rage across Japan. The so-called Space Invaders Part II Case is said to have been the first judgment in Japan to recognize computer programs as copyrighted work.

“Digital games are a much-debated topic in the field of copyright and intellectual property rights as they involve tremendous profits and affect many people,” says Masaharu Miyawaki, a researcher of copyright and intellectual property laws. While we are still in the early days of digital gaming history, various legal interpretations surrounding digital games have been issued over the past few decades. The case that found Pac-Man a “cinematographic work” under Japanese copyright laws is a well-known precedent among researchers.

As exemplified by Invader Game, it was common at the time to play at game tables in game cafés, and Pac-Man was one such game. The Pac-Man case emerged after the game maker sued a game café that illegally copied and reproduced the Pac-Man game tables. “Actually, the court’s findings in the Space Invaders Part II Case concerned the infringement of reproduction rights under the copyright law. However, even if a duplicated game table was placed in a café, that store could not be sued for such an infringement. That is because it was not the café that duplicated those tables. In this court case, by defining such video games to be “cinematographic works” under the copyright law, the act of letting others play at a game table that had an illegal copy of Pac-Man built into its motherboard was considered an infringement of the Screening Rights,” Miyawaki explains. Although the term cinematographic work under copyright law was originally defined with theatrical motion pictures in mind, this court case allowed it to be applied to games. “From this point on,” Miyawaki continues, “the understanding that ‘cinematographic work’ means all video output on a screen took hold.”

What about copyrights related to second-hand game software? There was a lawsuit in which a game maker filed a lawsuit against a second-hand game distributor. “In the case of theatrical movies, the ‘distribution right’ is granted as a film-specific right to control the transfer and lending of copies. This is because the traditional film distribution system was based on having a small number of copies of the film circulated from one theater to another for screening. If games were copyrighted as cinematographic work, this also means that distribution rights would be granted to the filmmakers (i.e. game makers), and only they would be allowed to reproduce them. However, the Supreme Court ruled that second-hand sales did not infringe on distribution rights because it did not follow the same form of traditional movies’ distribution model for reproductions, as copies of games were distributed in mass quantities on the premise that individuals or a few individuals would be enjoying them. The intent here was to say that the items that adopted the distribution model of second-hand CDs and books were not infringing on distribution rights.”

Although it was quite common to see cases in which game makers were suing pirate manufacturers when digital games were still new in the market until recently, it has become noticeably more common to see cases in which game makers are suing each other. Particularly common are the cases where the original game creator files a lawsuit against another, claiming the defendant’s game has imitated the idea of the plaintiffs’ popular game amongst their catalog of games.

“In this case, if the common aspects of the plaintiff’s game and the defendant’s game are ordinary and commonplace among the same types of games, this would not qualify as copyright infringement,” says Miyawaki. In general, the plaintiff claiming infringement must prove that the part the defendant imitated is unique to the plaintiff’s game. However, since it is difficult to show evidence that there is nothing else like this out there, in many such trials, the defendants must prove that such features are commonplace based on past games. Whatever the case, it is quite difficult to look through the vast number of past games, and even when they are found, it is even more difficult to obtain evidentiary material if they are old games.

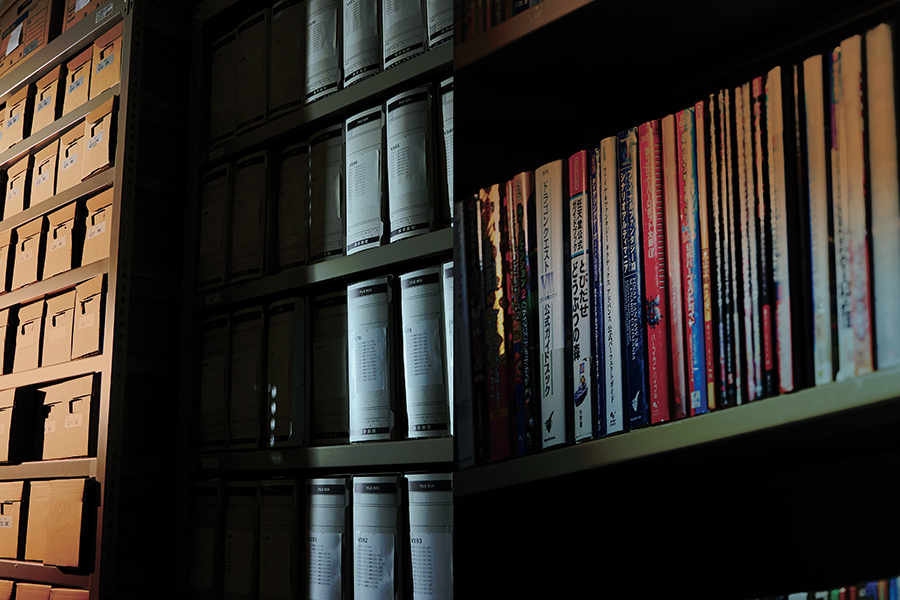

Such issues arise with patents as well, according to Miyawaki. “In the case of inventions related to the game systems and features, you must be sure that they have not been used in previous games, which is also no easy task. Even if the patent examiner is well informed about games in general and thinks, ‘surely, there must have been a game like that in the past,’ in many cases, they will not be able to find any evidence to prove it.” Not only is it challenging to locate the games, but the manuals do not provide thorough information about the game’s content, so one must even search through game magazines and strategy books to find it. It would be almost impossible to do so with limited time and resources.

As a result, undesirable patents, which may unnecessarily impede the production and distribution of subsequent games, may be granted. “As a legal scholar, I believe we must offer an interpretation of the law that prevents this from happening,” Miyawaki says.

Miyawaki is also a member of the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies (RCGS), the sole academic institution in Japan specializing in the field of games. RCGS is working on archiving all kinds of materials related to games, including gaming consoles, game software, instruction manuals, and game magazines. “From the standpoint of copyright protection, there is still a lack of consensus as to what extent we can make public such materials as a video game clip or the image of its package. As a pioneer in this field, RCGS hopes to establish a model that answers this question.” No doubt, Miyawaki’s research expertise will also be put to use in this endeavor.

- Masaharu Miyawaki

- Professor, College of Law

- Research Themes: Trademark Act; Unfair Competition Prevention Act; Copyright Act; Patent Act; Design Act; Tort Law

- Specialties: Intellectual Property Law; Unfair Competition Law