STORY #9

Post-disaster Mental Care that promotes Cultural Understanding

Yuanhong Ji

Professor, Graduate School of Human Science

The psychological care provided after the Sichuan Earthquake demonstrated vividly Japan’s extensive research on mental care.

Cultural differences can be found in how we conduct our interpersonal relationships, or in the manifesting symptoms of a disease. For example, the symptoms of neurosis appear in significantly different manners in Japan, China, and the U.S. Seclusive neurosis and scopophobia seem to be considered prominent in Japan, whereas severe psychosomatic diseases that manifest themselves as symptoms appearing directly on the body are more frequent in China. In the case of the U.S., a high incidence of drug dependence and violence is observed. In other words, neurosis symptoms differ by culture. “As such, when providing psychological support or treatment, understanding a person’s cultural background is essential,” explained Yuanhong Ji. Ji has conducted research on the relation between culture and multicultural counseling in clinical psychology. She is involved in activities, such as supporting foreigners and foreign students in Japan to adapt to their new cultural environment. In particular, since the 2008 Sichuan earthquake which occurred in her birth country, she has focused on exploring ways to provide culturally considerate mental care in post-disaster situations.

The Sichuan earthquake left 70,000 dead, 370, 000 wounded, and 18,000 missing (approximate figures); it was an unprecedented disaster in the history of China. After the earthquake, the Chinese Psychological Society asked Ji to serve as a mediator between the Association of Japanese Clinical Psychology and the victims of the earthquake in providing psychological support. As Japan is prone to natural disasters, there are numerous studies in Japan on providing post-disaster mental care and psychological support.

More recently, whenever a large-scale disaster strikes, teams of volunteers and rescue workers gather from around the world to provide aid. In situations like this, where diverse people are involved and psychological experts play a significant role, Ji warned that not all are aware of, for example, the risks of debriefing, based on her experience. She explained: “The term debriefing describes one of the support methods by which victims of disasters are encouraged to speak about their traumatic experience and let their emotions relating to such events out. Initially, this method was considered to be among the more effective methods of providing psychological support for victims of disasters. However, this technique is now believed to cause more anxiety in victims if administered immediately after the event and thus considered as something that should not be done.” At the Sichuan earthquake-affected area, however, a volunteer team from another country, which was not aware of this, encouraged the children to draw pictures about their experience in the disaster to express their feelings. Ji and her colleagues advised the Chinese Psychological Society to inform the volunteers that administering such expression therapies immediately after a disaster is not appropriate.

In Japan, the importance of respecting culture and religion in providing post-disaster mental care is emphasized, based on the findings of numerous studies on the Great Hanshin Earthquake. “In Sichuan Province, mahjong is played frequently by the locals and deeply rooted in their lives. A famous story has it that after the earthquake, while the volunteers were providing support activities, the victims sat around a table and started playing mahjong. Although the locals’ action did not sit well with the volunteers, it was proof that people were starting to feel a little more at ease and were able to regain their daily routines; psychologically speaking, it was a good sign,” explained Ji. It is with such understanding of culture and customs that mental care can take root.

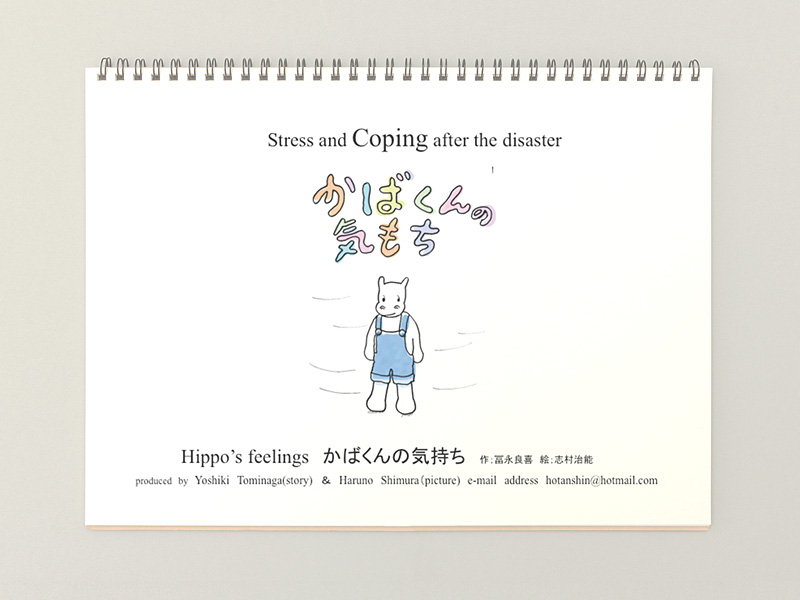

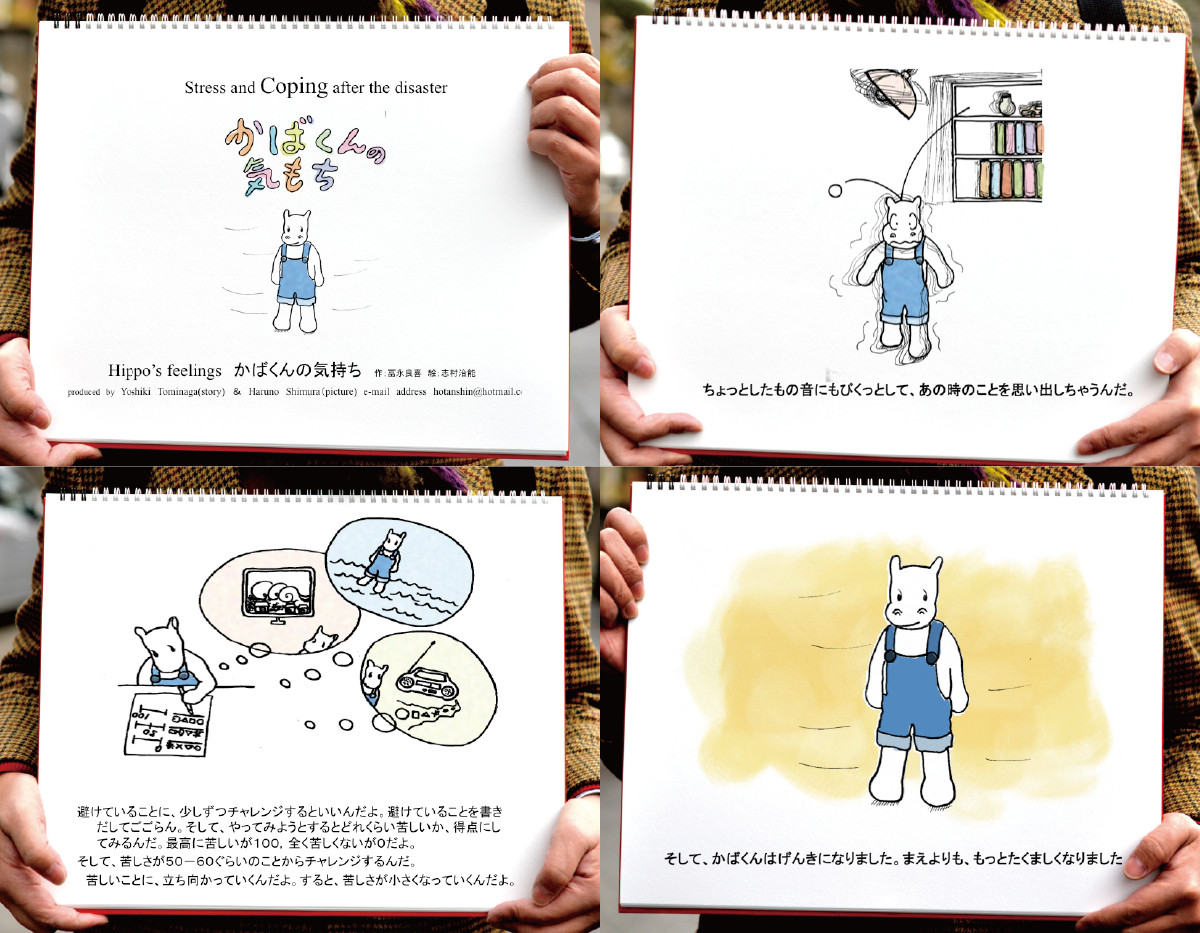

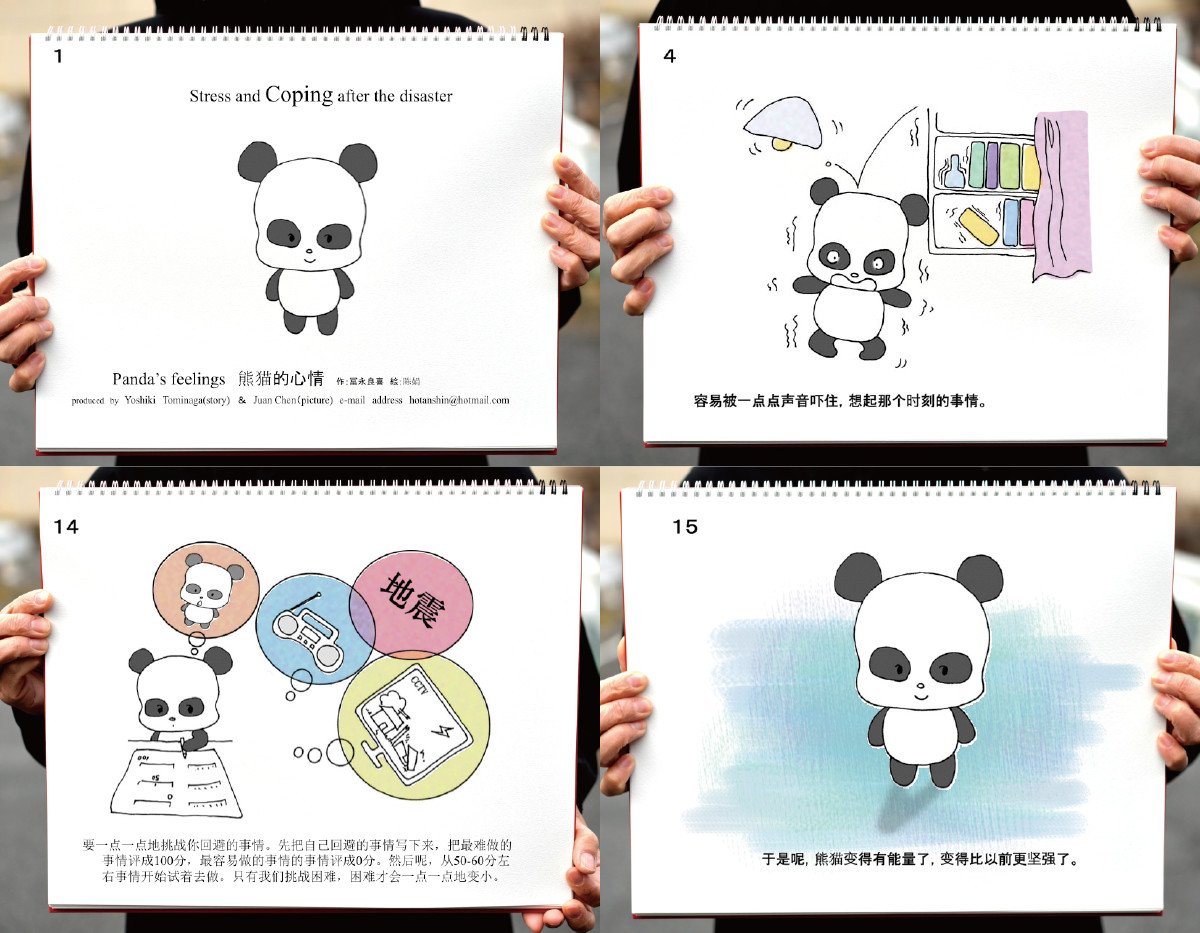

Ji and her colleagues also used a picture book, created by Japanese clinical psychologists on the subject of mental care, to teach children about stress management. At the time, she took special care to change the main character, from a hippopotamus to a panda bear, to make the book more appealing to the local children.

The picture book Kabakun no Kimochi (The Feelings of the Young Hippo) for learning about post-disaster mental care was created by Japanese clinical psychology specialists.

In addition, Ji and her colleagues offered “support for support groups” that also provided mental care. They conducted a mental health care training for Chinese specialists in the field of psychology at the Southwest University in Chongqing (photo below, right). They also provided consultation to the Southwest University volunteer teams at Chongqing’s hospitals at the disaster-stricken Deyang City (photo bottom of page, left). Moreover, Ji interviewed junior high school teachers in the affected areas to conduct a qualitative study on what considerations were given to the students who experienced loss. In this study, she found that, on the one hand, the teachers communicated actively with the students to help them recover their self-esteem, but on the other hand, they tried to assume the roles of social workers and psychological support specialists. By trying to satisfy dual roles, the teachers’ established role as an educator became ambiguous. This finding provided insights on ways to help other support groups.

Ji’s efforts in providing post-disaster psychological support were useful after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. “In particular, the common experience of the Sichuan and the Great East Japan Earthquakes is that they both had ambiguous losses.” An ambiguous loss refers to the type of loss of loved ones who are missing due to natural disasters or other events; in this type of loss, although the loved ones are not physically present, they are registered psychologically as being alive somewhere. “Although Japan is known for encountering frequent disasters, it had never seen as high a number of people going missing. The notion of ambiguous losses was a newly introduced concept (at the time),” Ji said.

Considering local cultures and religion is important in helping with mental and physical recovery due to ambiguous loss. “The challenge is that treatment methods and mental care for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were initiated in the West, and in many cases, they may not fit with Asian cultures,” Ji mentioned. Based on this insight, Ji and her colleagues, in collaboration with researchers in Japan, China, and other Southeast Asian countries, have tried to establish a mental care method that is uniquely Asian, taking local culture into consideration.

“When I came to Japan to study as a graduate student, I wanted to become a mediator between Japan and China. Now that I am a researcher, I want to deepen the relationship between the two countries through mental care, and extend this relationship to the rest of the world,” Ji said, as she shared her aspirations.

In its Chinese version, the book was modified to The Feelings of the Young Panda. After the Sichuan Earthquake, the main character was changed from a hippopotamus to a panda bear to make the book more appealing to the local children.

- Yuanhong Ji

- Professor, Graduate School of Human Science

- Research Subjects: expression-based psychotherapy, multicultural counseling, post-disaster mental care and culture

- Research Keywords: clinical psychology