STORY #6

Suicide Prevention Education for Students that the “cherish Life” Message does not reach

Kenji Kawano

Professor, College of Comprehensive Psychology

Education on suicide prevention begins with the creation of a supportive classroom environment.

“Your life is important. Therefore, you should not die by suicide.” Such sound arguments may at times take the children who are near the edge of death to the furthest point for which suicide prevention and educational endeavors are expected to lead them.

Kenji Kawano discusses the difficulties of suicide prevention based on his work experience at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and his involvement in national suicide prevention policies. In particular, it is said that suicide prevention measures in Japan targeting young people in their 10s to 20s are far behind other age groups. “As suicide cases suddenly jumped to 30,000 in 1998, measures against suicide have become a major concern for the country. While middle-aged and elderly men were the focus at that time, since then, the suicide rate in each age group has been declining, except for the teenage group that showed no sign of decline to date,” he says.

In the meantime, the Basic Act on Suicide Prevention was enacted in 2006, while the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) issued a manual titled Sustainable Child Suicide Prevention that Teachers Should Know in 2009 and another titled Emergency Response Manual for when a Child Suicide Occurs the following year. It is clear that the national government has also taken measures against suicide of young people in recent years, as these publications indicate. Another similar effort is seen in their 2014 manual A Guide to Introducing Suicide Prevention Education at Schools—Suicide Prevention You Want to Convey to Children. Parallel to these efforts, Kawano’s research group has developed a suicide prevention education program called “GRIP” to be implemented in schools.

The most outstanding feature of GRIP is its focus on group support, such as the classroom and the school itself. In the manuals published by MEXT mentioned earlier, learning about suicide and techniques to prevent it are strongly emphasized. However, the reality in the educational setting is that teachers tend to avoid talking about suicide because they fear they are inadvertently introducing suicide to children as an option in bringing the issue up. “What becomes a problem even more is that educating children using phrases such as ‘suicide is not good’ or ‘let us cherish our lives’ has an implicit danger, as these phrases tend to come across children who are already at high risk for suicide as a bunch of pretty words being shoved down their throats by people who have no idea what is really going on, and thus be rejected in such a way that the intention and purpose of the education would not reach them,” says Kawano.

In contrast, GRIP’s aim and purpose is to “create an environment where students and teachers can support each other.” By applying psychological theories and techniques, Kawano and others designed the program in a way that the whole class could accept the lessons and learnings without impediments for the children who really need the support. Its emphasis is not only on creating a supportive environment where students themselves can discuss issues when faced with difficulties but also on establishing a relationship of trust between them and adults whom they can turn to when they need to discuss any difficult situations they may face. The program is designed to be far more implementable in real contexts as it focuses on the class as a form of group support. As a result, it can provide an effective suicide prevention education without making “education about suicide” its premise.

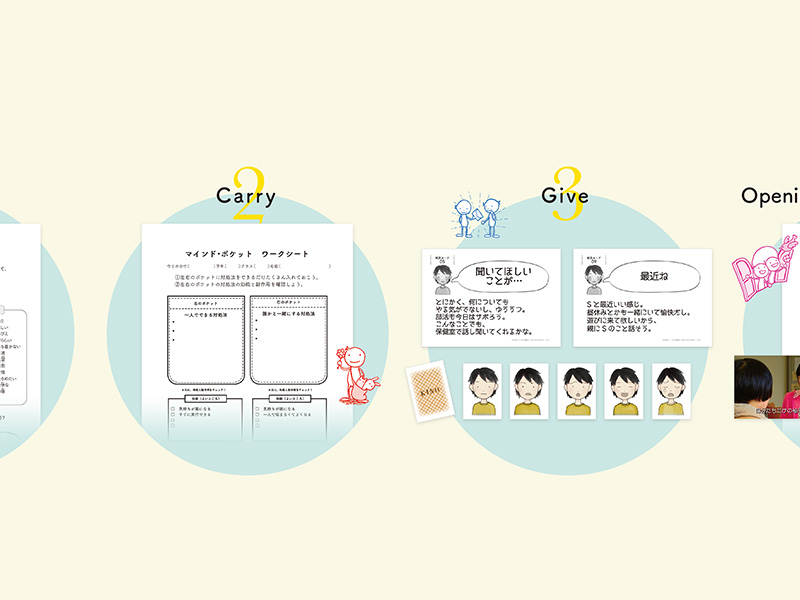

Another notable feature of GRIP is that it takes a gradual approach. The program starts with teacher training and then deepens learning over four deliberate stages: (1) to become an objective observer of one’s own inner state, (2) to cope with behavior, (3) how to discuss, and (4) to make decisions in conditions that are hard to handle. In each stage, students and teachers use games and group work so that the class and the school can become the focus of attention.

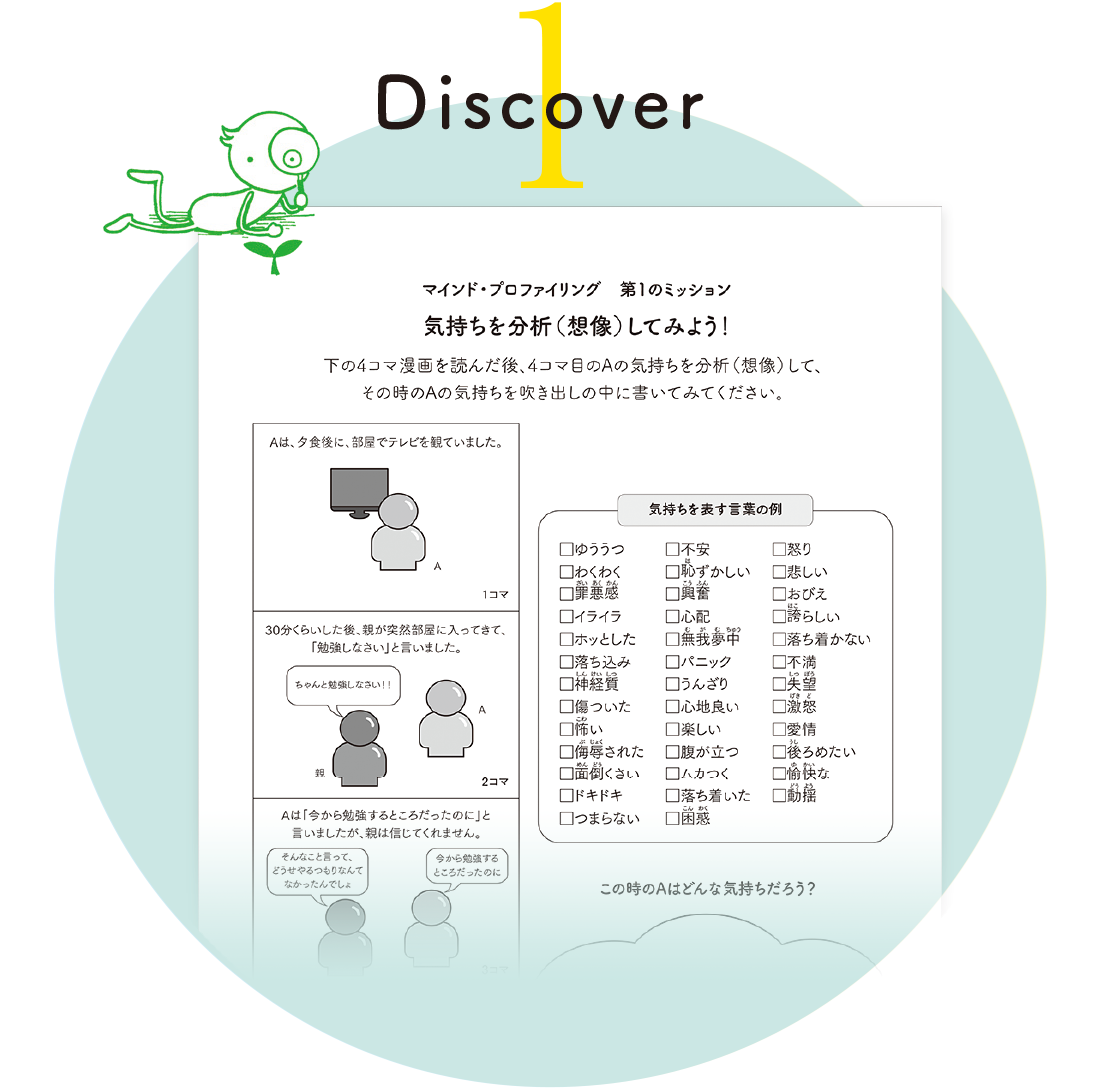

Mind Profiling

We want you to discover your feelings here. The aim here is to learn to perceive your own feelings so that you can effectively control them in difficult and unpleasant moments.

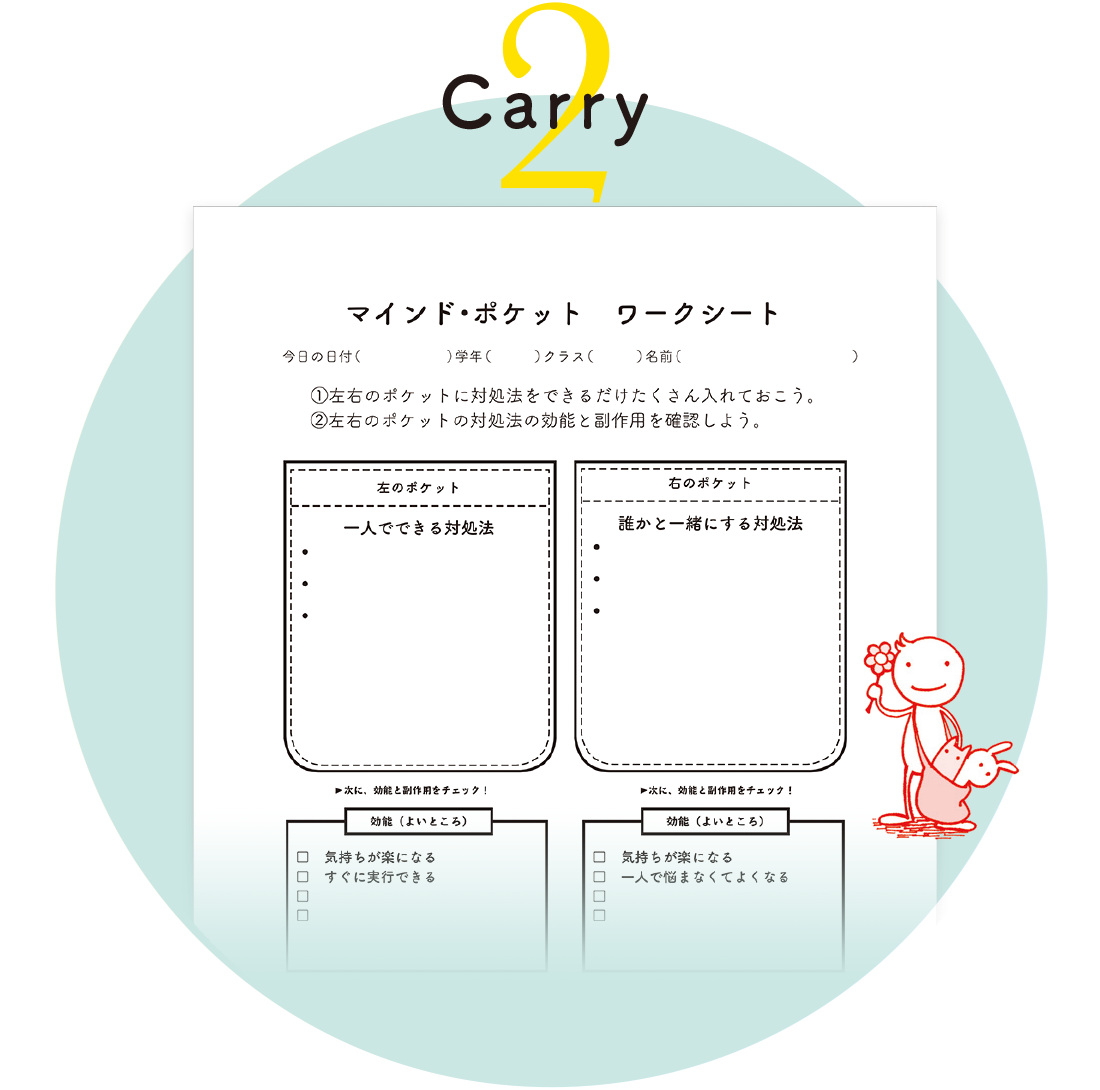

Mind Pocket

Here, you will learn coping methods through which unpleasant feelings are transformed. You will find your favorite method to be used when you are feeling down and place it in the pocket of your heart.

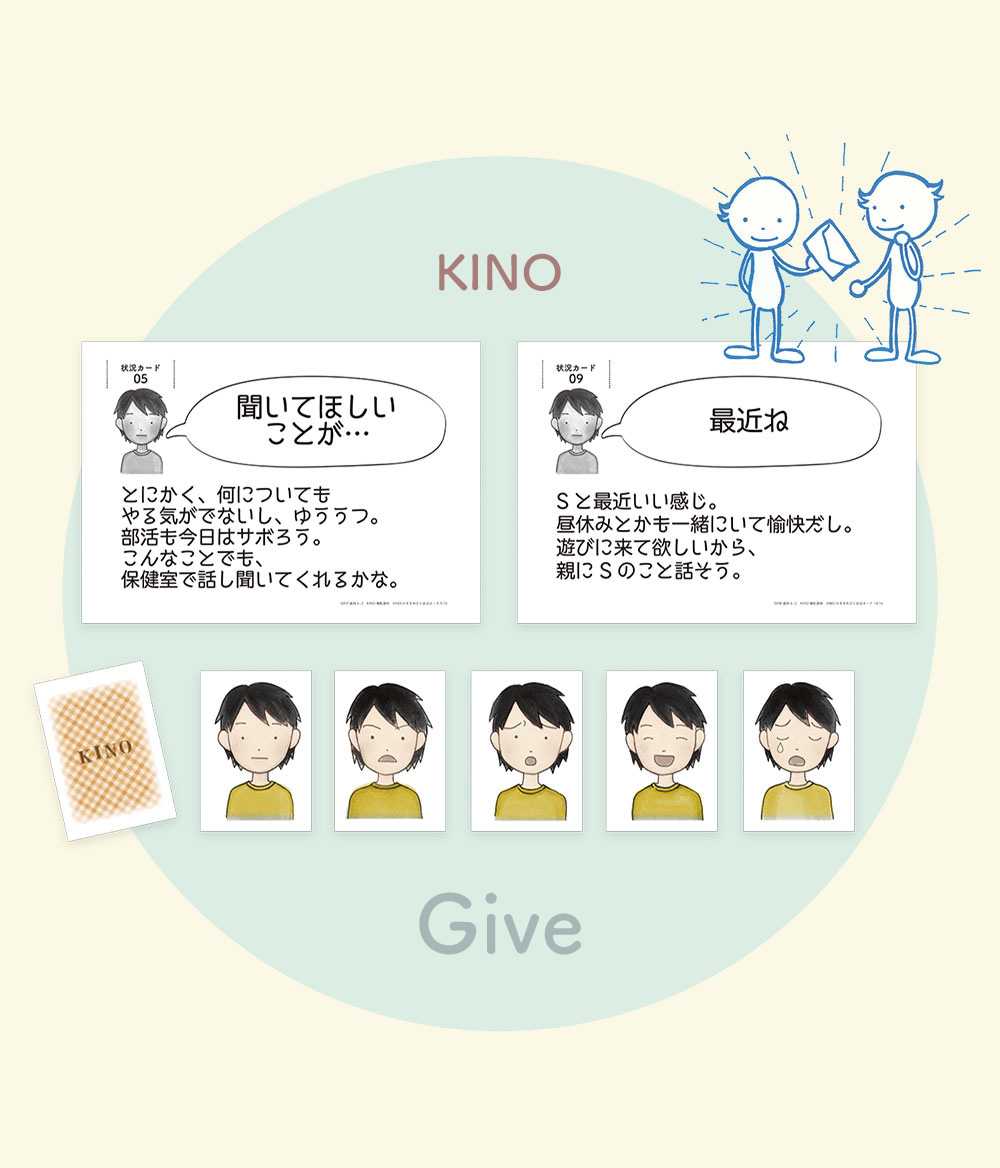

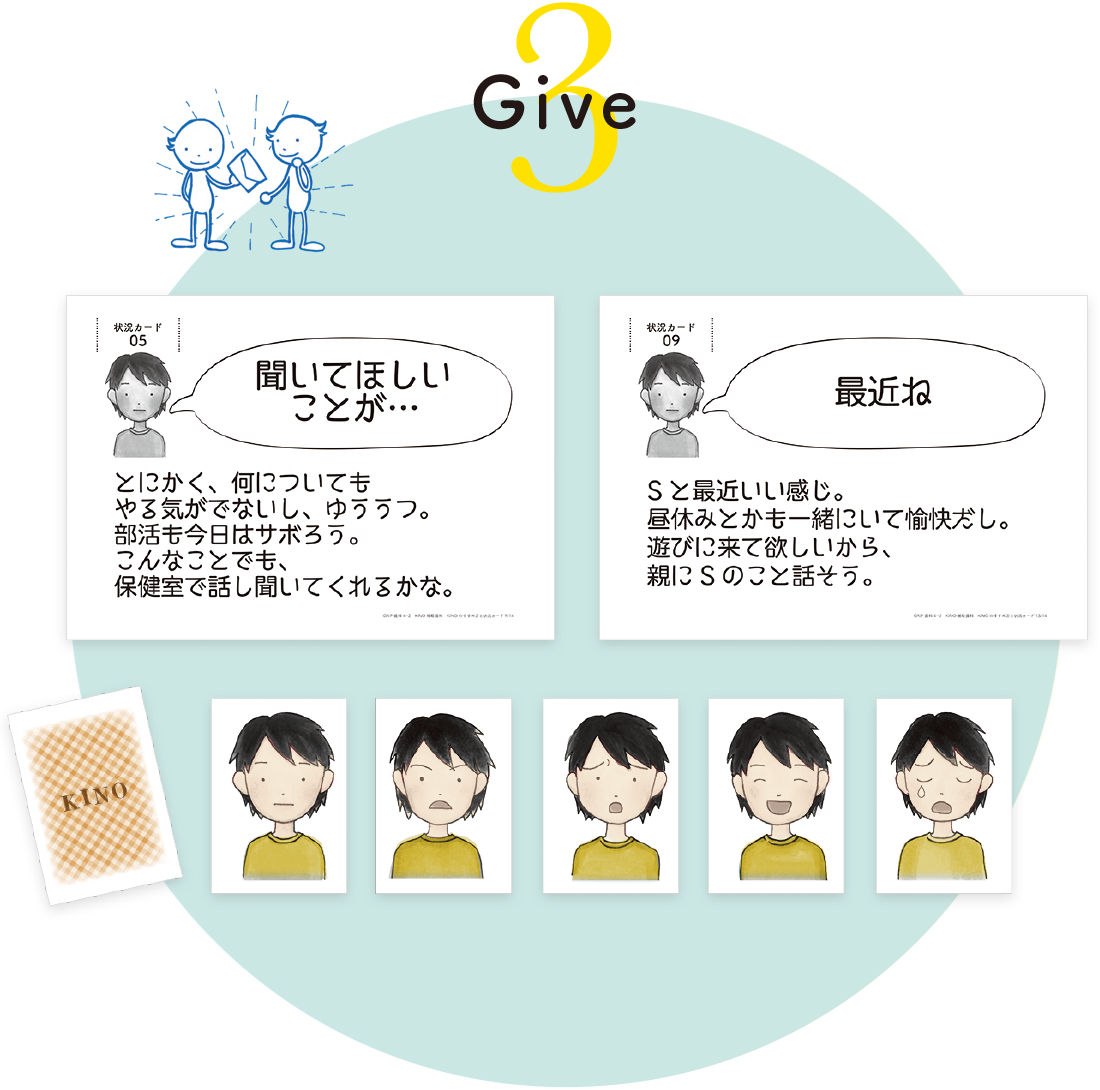

KINO

Here, you will think about how to convey your feelings. When you experience something that makes you happy, you want to tell others. When you go through a difficult experience, having someone to listen to you makes your feelings a bit lighter. Let us learn about the various ways to express your feelings.

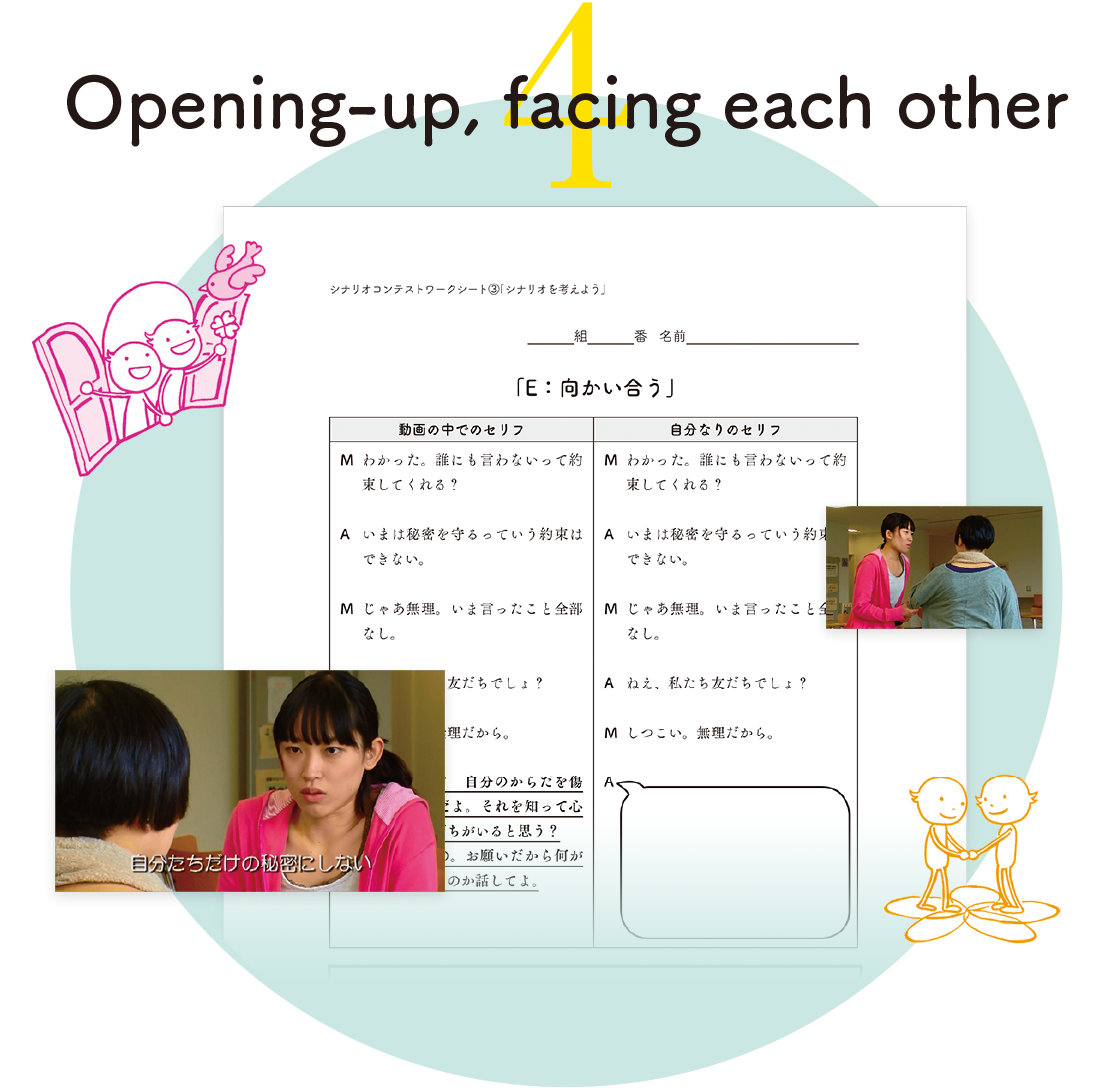

Scenario Contest

This is where you think about making responsible decisions. Trying to strive alone (or along with other friends) and being able to open up your thoughts and feelings to many people are two powers that you have to cope with difficulties. Let us understand how to use them.

“A necessary step in conducting suicide prevention education for students is to provide training for teachers as gatekeepers. After that, as a first step, we work on ‘mind profiling,’ which aims to ‘discover one’s feelings.’ In this step, they think about ‘their own feelings’ in different situations and, by expressing them in words, they gain the ability to organize and analyze their own thoughts,” says Kawano. In the second stage, they learn about “mind pockets,” which gives them skills to deal with negative feelings in order to recover a healthy state of mind. “You would write down on a picture of a pocket a coping mechanism of your liking, and then when you remember it, you go through the motion of tapping your pocket to check on it. Through a metaphor and physical imagery, one acquires the ability to deal with difficult situations.” In the third stage, an emotional expression game called “KINO” is used to consider our expressions when we share our feelings with others; the aim is to learn that different people have different ways of expressing and feeling their own emotions. Then, in the fourth stage, a “scenario contest” is conducted. Aided by video-based teaching materials, they learn through practice to ask and listen when they notice that their friends are suffering or in distress. Then, in the final closing session, they look back at each stage of learning and, once it becomes their own, the program comes to an end.

Kawano and his collaborators have made the GRIP program available online (https://www.shin-yo-sha.co.jp/grip.htm) so anyone can download the curriculum. A concrete guide on how to implement the program is provided in the book Suicide Prevention Educational Program in School Settings—GRIP. “Suicide prevention education does not end after undertaking the program,” Kawano explains. “Going forward, we need to practice by implementing the GRIP program, accumulate evidence, and polish the program into a highly relevant and reliable program by repeatedly examining the effect.” Kawano’s group is looking 10 years ahead as they continue to engage in suicide prevention education.

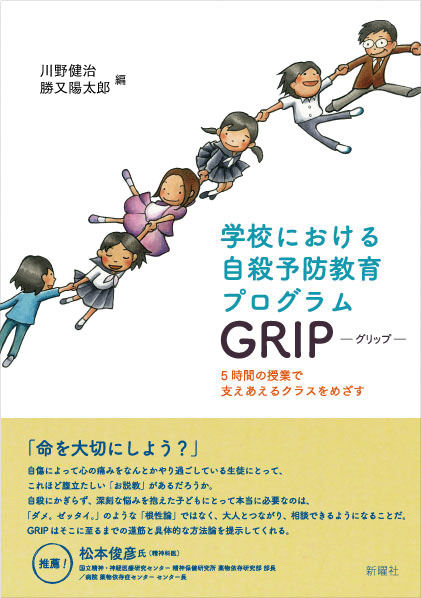

Suicide Prevention Educational Program in School Settings—GRIP—

A Five-hour Lesson Aiming to Create a Supportive Classroom

Kenji Kawano, Yotaro Katsumata (eds.)

Shin-yo-sha

- Kenji Kawano

- Professor, College of Comprehensive Psychology

- Research Themes: Awareness about suicide and suicide prevention; The gap between speaking and communicating; Community health and community design.

- Fields of Specialty: Community Psychology, Social Psychology, Suicide Prevention Studies