STORY #2

The Potential for New Kimono Businesses in Kyoto

Mari Yoshida

Associate Professor, College of Business Administration

Revisiting the Kyoto kimono industry’shigh-end/high-value-added survival strategy

Very few people in contemporary Japan still wear a kimono every day. Nevertheless, a researcher at Ritsumeikan University, Mari Yoshida, has investigated the potential for new business models for Kyoto’s allegedly outmoded kimono industry. Yoshida is interested in corporate innovation and value creation for customers, and has been exploring the “value of the kimono from the consumer perspective,” an approach that has not yet been adopted within the kimono industry.

In examining the reasons for the decreased size of the kimono market, Yoshida notes that, to begin with, there is a common misunderstanding. While many kimono-related businesses believe that consumers’ loss of interest in kimonos is related to the clothing being incompatible with modern lifestyles, she found that this trend was already evident in the latter half of the 1970s. Kimono production peaked during Japan’s period of high economic growth, but then decreased rapidly in the 1970s. However, manufacturers’ prices of kimonos continued to increase, despite the drop in production, until the collapse of Japan’s asset price bubble economy in the early 1990s. According to Yoshida, what is notable is that, with the downturn in production, kimono-related businesses began to base their business models on the sale of “high-end/high-value-added” merchandise. She explains that such models were successful principally because both production and distribution were centered in Kyoto.

Kyoto had established the necessary brand power on which the production of high-value-added merchandise could be based, and was home to the techniques and production systems used for Kyo-Yuzen dyeing and Nishijin textiles. In addition, Kyoto’s Muromachi district, with its experts in wholesale and retail sales, was the center for trading in kimono-related products. The industry adopted a survival strategy of shifting from Kyo-Yuzen dyeing and Nishijin textile production to hand-painted dyeing on pure silk and lavish obi sash textiles, made with gold and silver thread. Owing to the price increases, kimonos came to be considered as formal attire for special occasions only, and were treated as “assets.” In addition, prices rose even higher as a result of the industry’s peculiarly complex modes of distribution.

Thus, a new business model developed, in which added-value was based on the perception that kimonos are “formal attire,” which changed the structure of the industry. According to Yoshida, while the managerial ability within the Kyoto kimono industry deserves recognition, the condition of today’s kimono market is the result of the collapse of the aforementioned business model. This collapse began when the asset price bubble burst, reducing the number of high-income earners who purchased kimonos.

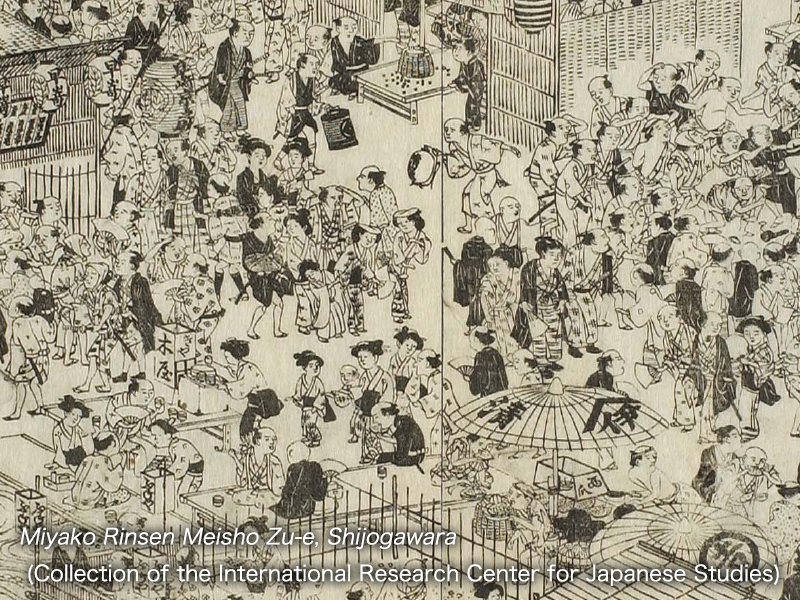

Homongi (semi-formal kimono for women), white silk with Ritsumeikan’s “R” background pattern, and “Snow, Reeds and Mandarin Ducks” by Jakuchu Ito in Yuzen dyeing

Production/photography: ZONE Kimono Design Institute (Collection of the Art Research Center (ARC) of Ritsumeikan University);

original painting: “Snow, Reeds, and Mandarin Ducks” by Jakuchu Ito, Etsuko & Joe Price Collection

In FY2013, the ARC, which conducts digital archiving of Kyo-Yuzen designs and research on actual conditions of Kyo-Yuzen,

ordered and produced hand-painted Yuzen and stencil-printed Yuzen kimonos, and recorded the process using videos, photos, and interviews

in order to investigate and record the current Kyo-Yuzen situation (see STORY #1).

In terms of why businesses have not yet been able to identify a strategy that could drive a recovery in the kimono market, in addition to their lack of understanding of the market, she notes that these businesses have not been able to identify the “value of kimonos for consumers.” Without understanding consumers’ needs, it is not possible to provide products that will sell. Thus, she conducted a survey research of today’s kimono users and identified six factors related to consumers’ opinions on the “appeal of kimonos” and the “value of kimonos.” Then, she performed multiple regression analyses on variables related to these factors and consumer behavior. Her results show that the “value of a kimono” differs for kimono wearers (indicated by a high frequency of wearing kimonos) and kimono buyers (indicated by a high annual expenditure on kimonos), who purchased them for formal occasions.

Kimono wearers find value and enjoyment in relatively cheap antique or ready-to-wear kimonos, made from synthetic fabrics by mixing and matching colors and designs. In contrast, kimono buyers find value in the “sense of specialness” they obtain from ordering from a reputable kimono maker and choosing the materials and colors of the threads. Based on her analysis, Yoshida notes that businesses have not recognized these different types of consumers and, thus, are all competing for the same consumer market. She believes that the overall kimono market should grow if businesses recognize each consumer market and pay attention to each other’s markets.

According to Yoshida, the main requirement for halting the decline of the kimono industry is a clear understanding of the different markets and consumers. As a successful example, she cites one of Kyoto’s largest wholesale producers of dyed kimonos, Chiso Co., Ltd., which has been in business for more than 450 years. While high-end Yuzen kimono accounts for 90% of wholesale sales of Chiso, it opened its own retail store, called Sohya, in 2006. By selling merchandise at prices well below the usual Chiso prices, the company succeeded in reaching the kimono wearer market, who enjoy kimonos as fashion items. She believes that Chiso has been successful because it has been able to differentiate the value of kimonos for different customers, thus adapting flexibly to that market.

According to Yoshida, the key to reviving the kimono industry is actively marketing to different markets and customers, something that has been lacking in the industry to date. In this regard, she is of the opinion that solutions can be generated by combining Kyoto’s location and craftsmanship. As an example, she cites a new entrant to the market that will be partnering with a maker of Nishijin textiles to identify a target market. She believes this is probably the “biggest and last chance for the kimono trade.” In addition, demonstrating her enthusiasm for the topic, she says, “As a researcher, I’d like to contribute to the support and cultivation of entrepreneurs who will build new businesses that will inject momentum into the kimono trade.”

Mari Yoshida

Associate Professor, College of Business Administration

Subject of Research: value co-creation, market formation process analysis, effectuation (logic of entrepreneurial decision-making)

Research Keywords: marketing, strategy