Transforming desperation and a cruel reality into humorous songs

Michael row de boat ashore, Halleluja!

Michael boat a gospel boat, Halleluja!

Jordan stream is wide and deep, Halleluja!

Jesus stand on t’oder side, Halleluja!

The American folksong, “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” is well-known even in Japan, but how many Japanese know its lyrics in the language of its origin? And how many people truly understand its meaning? Its slow melody gives the sense of an idyllic atmosphere, but the truth may be quite different. As Wells Keiko explains, “in fact, this is a song where one is praying to the archangel Michael to row the boat and take the singer’s soul to heaven (ashore). It is a song about wishing for life after death in the face of harsh realities.”

Wells became attracted to the power of the vernacular and focused her research on American lyrical poetry, songs, and stories within the broader context of vernacular literature and culture. Yet, the range of content she covers in her studies is vast and includes literature from the work songs sung by African Americans during the era of slavery to modern-day pop music. She deeply analyzes the lyrics of the songs and the stories told throughout history and attempts to understand the meaning hidden within the words, unravelling the society and culture underlying them.

Slavery was abolished in the United States, including its southern states, in 1865, but discrimination continued against African Americans.

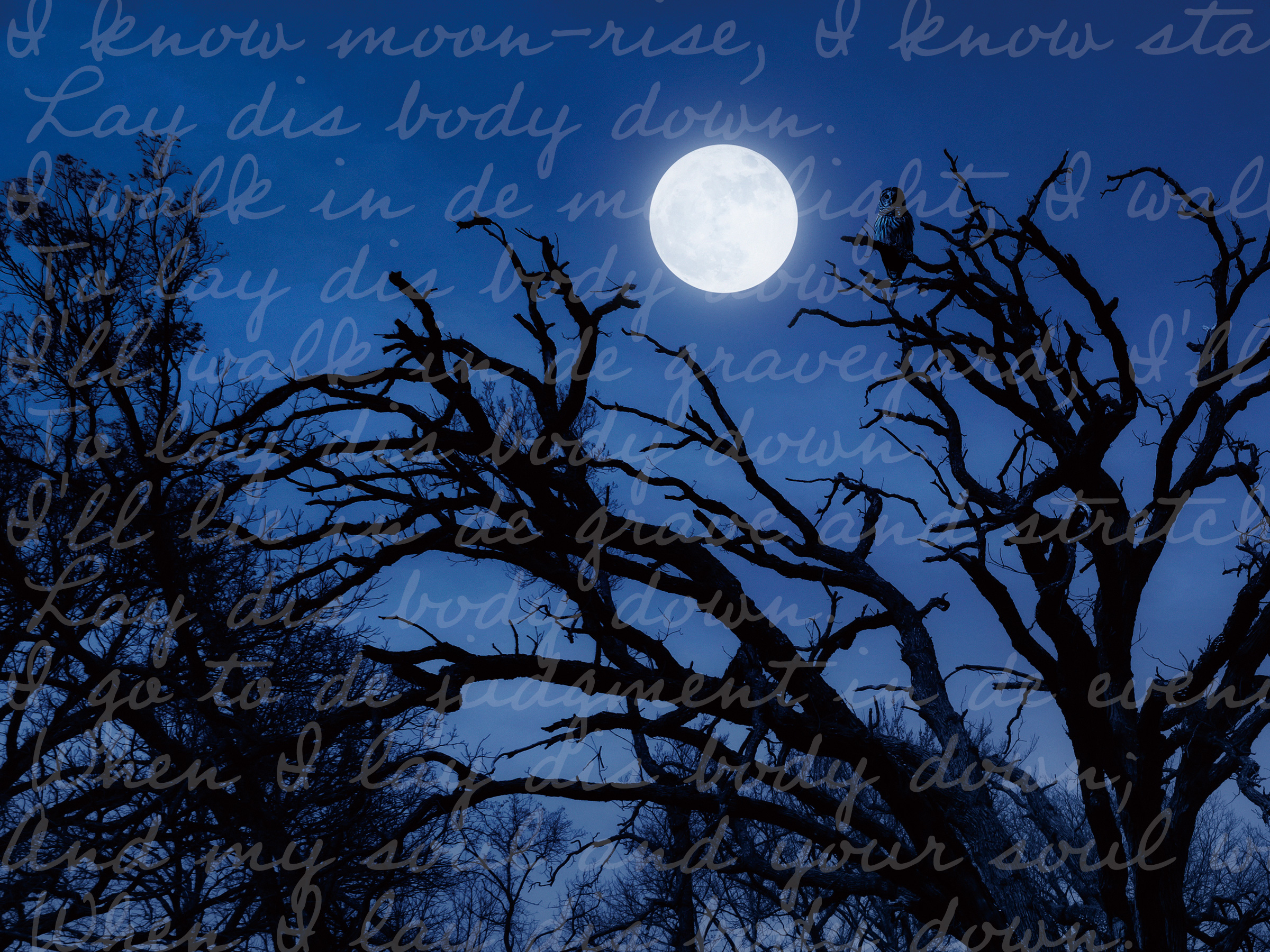

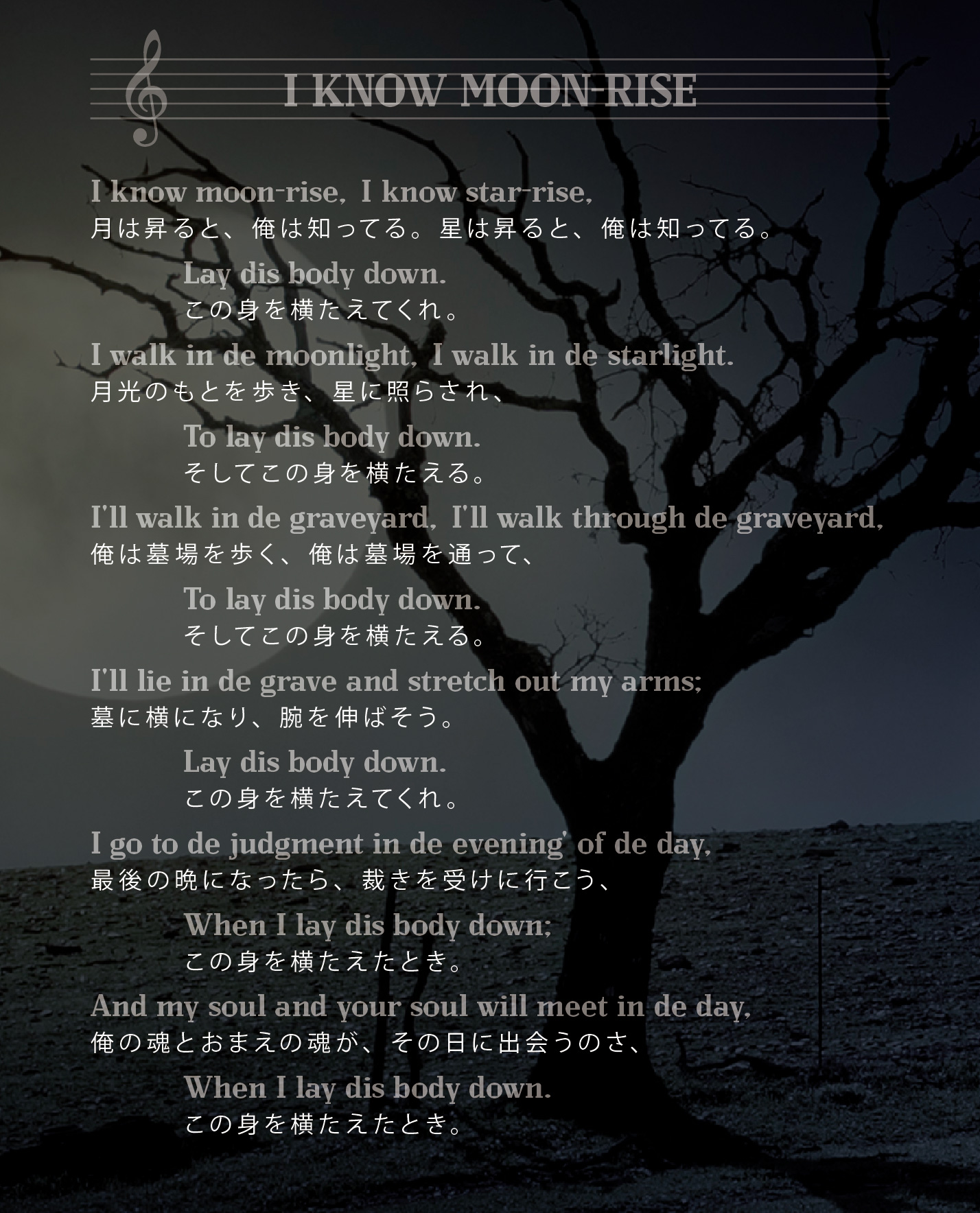

“Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” is also an African American work song from the slavery era. A major characteristic of these songs is what is known as call and response, a traditional communication style used in cultures of African origin. The monotonous but powerful phrases repeated in these work songs deeply moved Wells. She says, “one of the means by which people endure their difficult lives is by vocalizing it. Listening to other people’s voices can give us great relief.” Many of the work songs created during the era of slavery touch listeners’ hearts. For instance, “I know moonlight, I know starlight, I lay this body down,” is a repetitive line from a song about the feeling that one gets when one has lain under the light of the moon and the stars; the singer is too weary to get up, and finds peace in death. “Instead of vividly expressing their difficulties and cruel reality, they transform their desperation into beautiful or humorous lyrics. From these songs, I feel the strength of the singers and see a spiritual way of living in which one has detached oneself from their physical reality,” says Wells. She feels the mission of a researcher must be to extract the meanings hidden deep in these lyrics, which one may not notice at first glance, and carefully listen to the pleas of these song-writers.

I know Moon-rise (excerpt)

From the Negro Spirituals, an article that contains songs that Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823-1911)—the colonel who led the first black troop in the Union Army during the Civil War in the U.S. (1861-65), and a staunch abolitionist—had collected while he lived among African Americans.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson. “Negro Spirituals,” The Atlantic Monthly, XIX (June) 1867.

Wells points out that metaphors, double entendres, the reversal of values, innuendos, and allusions can be found not only in these work songs but across all African American literature. The folktale, The Hare and the Tortoise, as told by African Americans, is one example.

This story is well known in Japan as well, but its contents are quite different. In the African American version, the tortoise collaborates with his family to forestall the hare, who is running hard, so that he may win the race; the tortoise cheats, so to speak. As Wells explains, “morality and rules have meaning when they are shared among a community who agree that following those rules profits the community. The morals and rules of the hare do not profit the tortoise, who is forced to compete under overwhelmingly unfavorable conditions. Therefore, it is understandable that the tortoise turns the hare’s morals and rules on their head, considering them to be ‘bad.’ This is what is meant by the reversal of values.” Instead of pity or grief, Wells finds, in such stories, the art of survival under oppression, trauma and despair, and the ability to create joy that one can be engrossed in under desperate conditions.

In the stories of the African Americans, who at times felt that God had abandoned them, one often finds words that indicate they had the devil, and not God, on their side. “If God is not saving them from their suffering, then in a sense, it is natural for them to feel closer to the devil. Such feelings must have been the reality for some African Americans.”

The African American Spirituals influenced modern-day music all over the world. For instance, Blues has had significant influence worldwide. According to Wells, a type of song popular among the African Americans as entertainment, likely in the late 19th and 20th centuries, was commercialized when recording devices such as records and radios were developed. It then achieved widespread distribution, and eventually began to be categorized as a genre called the Blues.

The literary features of the Blues are found in its lyrics, which comprise motifs depicting anxiety, melancholy, loss of homeland, self-pity, loneliness, and difficulties. The Blues also vividly reflects sensibilities and techniques passed down from the era of slavery, such as a teasing tone to represent a dire situation, as if the cruelty was not being faced by the singers themselves; begging the devil, not God, for help; and looking to death as an escape from loneliness. The call and response form is also retained in the singer’s interaction with the guitar. “Those oppressed to the extreme had their will and freedom to share feelings crushed. Yet, through lyrics that were open to interpretation, they obscured ideas that could put them in danger. By making the lyrics absurd, they could expose their true feelings to others,” Wells elaborates. She also says that another unique style of singing, in which the singer appears to be muttering, is a manifestation of this.

Wells traveled across the United States to collect the songs and stories that remain in each region. She says that getting to experience local weathers and climates helps her understand the backdrops of the songs much better. Above all, she finds joy in meeting people through songs, and each encounter serves to strengthen her feeling that “people never fail to sing, and that really is amazing.”

- Wells Keiko

- Professor, College of Letters

- Research Themes: Systematic research of the vernacular culture with a global perspective. In particular, research on the propagation and transformation of migrants’ experiential memories; songs and stories; music-related culture; a comparative study of cultures in relation to lyrics in English; and the comparative study of Japanese legends, stories, and the performing arts. Her focus is on folksongs, folktales (fairy tales and folklore), and oral traditions.

- Specialties: Anglo-American and English literature, literature and folklore, comparative literature and culture