STORY #4

The Unknown History of Buraku in Kyoto from the Perspective of Public Bathhouses

Miki Kawabata

Senior Researcher, Kinugasa Research Organization

Public Bath Movementthat influenced Sentos of Japan

Kyoto is renowned as a “city with many sentos (public bathhouses)” in Japan. When walking in the city, you can see buildings here and there with Norens (entrance curtains) that read Yu, meaning hot water—a sign for public bathhouses. Some have been in business since before the Second World War.

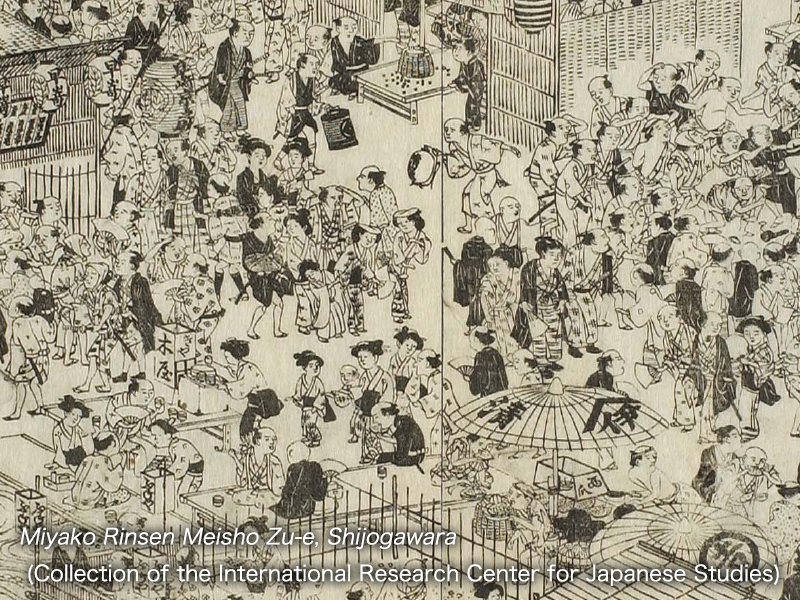

In Japan, bathing habits have existed for a long time, and there are many records and drawings showing that public bathhouses were popular in the Edo Period as places for socializing and recreation for the common people. Historical studies on public baths have often discussed the subject by focusing on aspects of customs and culture, but Miki Kawabata examines “public baths” from an original point of view, and has gathered attention both in Japan and abroad. Currently, she is interested in the formation of the national characteristics of the Japanese people around “cleanliness.” “It is often said that Japanese people are a clean nation, but when was this discourse born and how has it been nurtured?” Kawabata questions. She is trying to clarify how physical and spiritual norms related to “cleanliness” in modern Japan were born and had changed. What was especially striking was that she spoke from the vantage point of public baths regarding the change in the Japanese norms on cleanliness in relation to the Public Bath Movement, which was a global movement that primarily took hold in the West.

“It is said that in ancient Japan there were customs and rituals called misogi (purification ceremony), and ‘cleanliness’ included not only physical things but also had spiritual and moral meanings,” Kawabata says. It has been pointed out that frequent bathing in the Edo Period meant cleansing the filth off of one’s heart, such as sexual desires and greed for money, and keeping one’s self morally pure. Once entering the Meiji and Taisho periods, new meaning, such as sanitation, were given to the bathing and use of public baths. It is said that these developments were influenced by the Public Bath Movement that spread throughout Europe and the U.S. since the middle of the 19th century.

According to Kawabata, the Public Bath Movement started in England in the 1820s and was a movement that established bathhouses in areas where poor people, such as immigrants and laborers, lived. The importance of “sanitation” was discovered due to the development of medicine and hygieiology, and people realized that bathing was good for preventing infectious diseases and conserving health. In addition, it was believed that “physical cleanliness was a proof of being ‘a citizen’ and it functioned as a social work to educate people as ‘members of civil society.’”

“Since the missions Japan sent to Europe and the U.S. during the Meiji Period witnessed this, the recognition that bathing and public baths are meaningful in terms of hygiene was shared in Japan too. As a result, public baths were built by the government,” Kawabata explains. In his book Visit to the West – the Poor and Relief, the social worker Takayuki Namae talks about the necessity of inexpensive public baths where laborers, as well as their families, could take baths. In the Taisho Period, public baths were discussed under the framework of social projects under the new purpose, sanitation.

Furthermore, Kawabata focuses on municipal public bathhouses from the Taisho Period, which were established by the government mainly in cities, and she takes a close examination at their establishment processes. One part of her research is on such establishment process of municipal public baths by Kyoto and their operations after establishment.

“A movement for establishing public baths as a social work occurred in Japan with the influence of information from the West, and in Kyoto during the Taisho Period, public baths were built for the Buraku (a settlement of people discriminated lower class people),” Kawabata said. She explained that the establishment of public baths started as a social work aimed at improving the lives of the Buraku in Kyoto, such as using the revenue from bathhouses as a financial resource for the Buraku in order to relieve people suffering from their poverty-stricken lives.

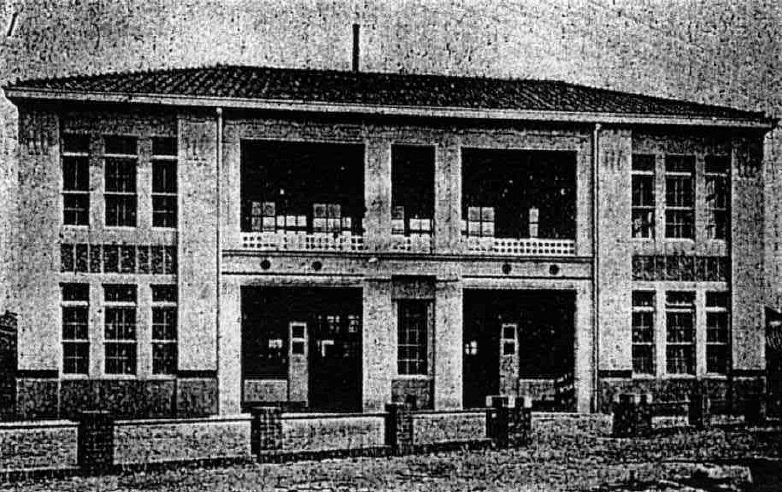

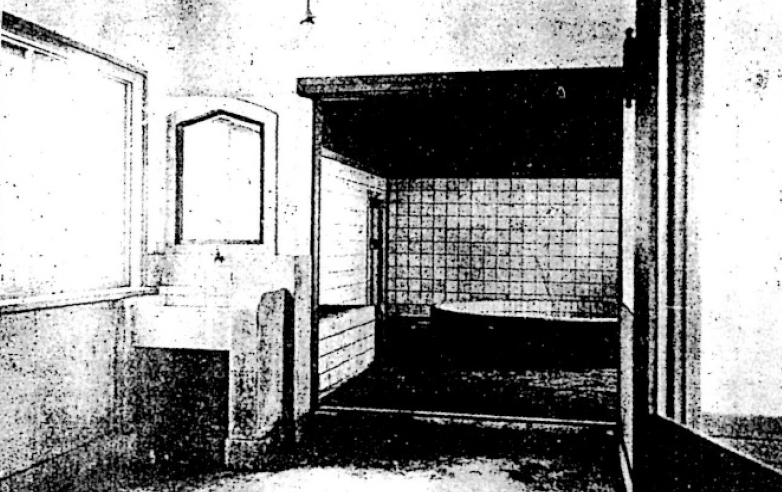

Public baths in the Taisho Period*. Some were equipped to be meeting places and vocational training facilities, and they also served as a center where people of an area gathered.

* Social Department of Kyoto City, “13th Publication Series of the Social Department of Kyoto City, Public Bathhouses of Kyoto,” Social Department of Kyoto City, 1924. Reprinted (Modern Era Documents Publishing Association ed. “Japanese Modern Urban Social Research Data Collection 4, Social Research Report I on Kyoto City and Kyoto Prefecture, 11 1924 (1)” Modern Era Documents Publishing Association, published in 2001.)

According to Kawabata, who thoroughly examined documents such as the Buraku history in Kyoto and the Hinode newspaper of that time, the first municipal public bath built in Higashi-Sanjo in September 1921 contained a barbershop on the first floor, along with a hall, a Buddhist altar, and a library box among other installations.

“Later, among the municipal public baths that were built one after another in Kyoto City, some were equipped with meeting places and vocational training facilities for those with special needs. These municipal public baths were not only providing a place for people to bathe and improve sanitation, but they are thought to have functioned as a place for improving the living environment of the communities and as a center for people in the area to gather,” Kawabata argues.

Also, establishing the water supplies was an essential prerequisite to install municipal public bathhouses. Until then, some Buraku communities had inadequate water supplies, and water pipes had not been maintained. The establishment of municipal public baths also led to the acquisition of infrastructure, such as that of water supply systems.

With Buraku history and municipal government history alone, it is difficult to grasp this tough and graceful attitude of the people who lived through their experience as the discriminated Buraku community. “Some things come into view precisely because we are focusing on the public baths,” Kawabata says.

The world that can be seen by looking at the sentos is quite a diverse one, including the Public Bath Movements around the world and the national characteristics of the Japanese people.

- Miki Kawabata

- Senior Researcher, Kinugasa Research Organization

- Subject of Research: the beginning of nationality for cleanliness in modern Japan; public bath and “Kokumin-Doutokuron”

- Research Keywords: history of sanitation, medical history, scientific sociology / history of science and technology