STORY #5

What are the Policies for Preserving Kyoto’s Townscape for the Next Generation?

Tomohiko Yoshida

Professor, College of Policy Science

Currently, Kyo-machiyas are hot in the previously owned residential housing market.

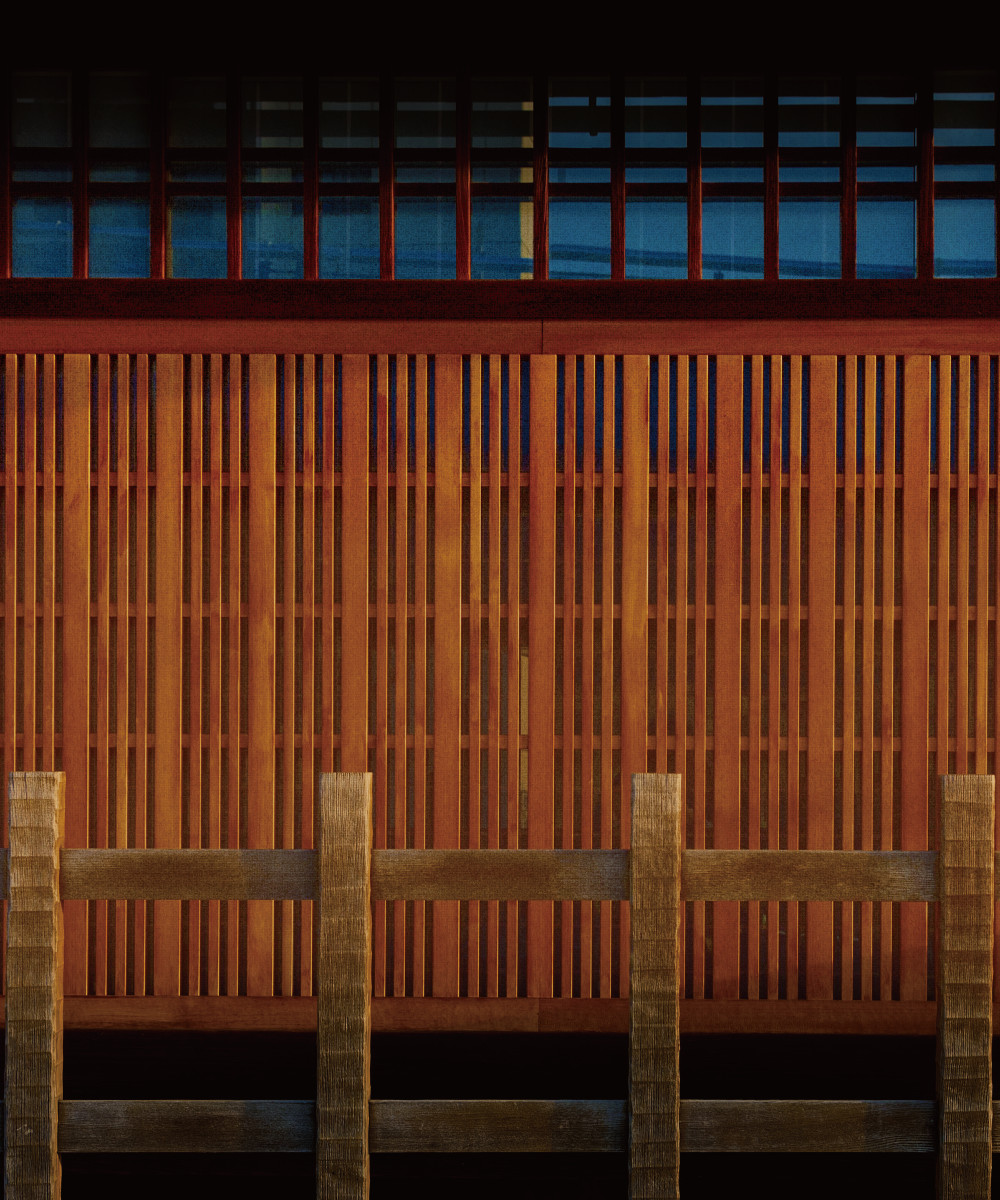

Streets that connect a grid of shops, the Machiya (townhouses) that extend deep into the back and their narrow entryways, the narrow alleys—in addition to the historical buildings, Buddhist temples, and Shinto shrines, the living environment of historical city Kyoto comprises such elements in its residential areas. Tomohiko Yoshida, who specializes in urban and living environment policy, is fascinated by Kyoto as a city and is keeping track of the transition of its urban form.

He says, “The advantage of Kyoto is that it was not bombed during the Second World War, and the city’s renewal has steadily continued from the modern era to this present day.” There are quite a few townhouses in the city that were constructed more than 100 years ago. On the other hand, the aging of residents has progressed, and about 10% of the townhouses are vacant. It is not that the government is looking on with folded arms. In Kyoto City, the “Ordinance on Preservation and Utilization of Historical Buildings in Kyoto City,”—which utilizes the exclusion from application of provisions in the Building Standard Law—was put into place for the purpose of “preserving historical buildings in good condition, such as Kyo-machiya that have scenic and cultural value, and putting them in use, as well as passing them down to the next generation.” Yoshida also advocates a political direction for these old buildings based on the results of studies on the urban structure and living environment of the Kyo-machiya.

For example, there is a study that details the supply situation of previously owned residential houses in Kyoto City as one of the indicators for evaluating the characteristics of the urban structure of the city. Yoshida analyzed the geographical distribution of Kyoto City, focusing not only on Kyo-machiya but also on the location, specifications, and price of all detached houses, including older detached houses and apartment buildings. He brought to light the price differences, as well as tendencies in total floor area and number of rooms using districts, such as Higashiyama and Kita Ward, and also locations and selling prices that are often available in the market. He has also identified a characteristic referring to the “undersupply of used detached houses,” which is especially prominent in the downtown area.

More recently, Yoshida has also conducted a new study focusing on used residential houses that are “prohibited from rebuilding” (residences where only renovations are permitted because they are not connected directly to roads) in Kyoto City. He investigated the market conditions of various used residential houses, from Kyo-machiya that are considered to have a long and distinguished history to relatively new terraced houses of residences constructed about 50 years ago.

“There are currently two types of properties that are ‘prohibited from rebuilding’ that still remain in Kyoto City. Old Kyo-machiya, which were built between the modern era before the Second World War to immediately after the end of the war, and relatively new terraced houses that were built during the period of high economic growth around the 1960s,” Yoshida says. Regarding the site arrangement of Kyo-machiya, they are generally located deep in the sites of the so-called “bed of the eel,” which is said to be a narrow entrance facing a street where the building is split into the landlord’s house on the front and a rental house on the back facing an alley. Many of the rental houses in the alley are buildings in a row-house format with three or four connected houses. Regarding the site’s arrangement, the entrance that is in front is the original landlord’s house facing the street, while toward the interior, it goes through a private path called Fukuroji (cul-de-sac street), which is less than one-meter wide. While they are both called Kyo-machiya in recent days, in the case of such Fukuroji, the residential building in the back does not meet the requirements of the Building Standard Law that stipulates that “the building must be in contact with a road by two (or) three meters or more.” Therefore, rebuilding is prohibited at such places that have “inadequate connections,” and the building is classified as property “prohibited from rebuilding.”

Yoshida explains the actual situation, saying, “as for properties that cannot be rebuilt since the market price is set a little lower, those locations that are considered Kyo-machiya sell relatively smoothly.” Because renovation is allowed (though rebuilding is not), these buildings are being renovated as houses or as accommodation facilities; they enter the market one after another. The tasteful atmosphere is popular among foreign tourists as well.

On the other hand, some buildings prohibited from rebuilding, which were constructed 50 years ago, also have a row-house format. However, because they are relatively new and are not located in the downtown area of Kyoto City, it is difficult to sell them as Kyo-machiya, and thus they do not sell well. “In order to continuously maintain the urban landscape, it is necessary to take an extensive view of the entire, previously owned residential housing market, grasp its characteristics, such as locations and specifications, and make use of this when formulating policies,” says Yoshida.

Kyo-machiya, another world which can be found at the back of cul-de-sac streets.

In considering a sustainable city, the people who live there and the way they live are also important variables. Yoshida says, “What is ideal for maintaining residential areas is the presence of men and women of all ages, and residents of various generations.” From this point of view, he focused on the importance of households with young families living near their parents, and by targeting areas of detached houses in the suburbs of Kyoto City, he analyzed the difference between households that managed to live near their parents by moving into the area, in contrast with those that did not. “Living nearby” as used here carries more of a psychological meaning, which is to say, to live in a range where it is possible to come and go between the parent’s and child’s households within 30 minutes, irrespective of the means of transportation.

Yoshida says, “In the suburbs of Kyoto City that I surveyed, there were many of the children’s generation who lived close to the husband’s parents, and in particular, there were many households in which both the husband and wife worked.” He analyzed the results to mean that “the determining factor in moving closer was that the children were worried about their parents, rather than them wanting the parents ‘to take care of their grandchildren.’” Meanwhile, in the downtown area of Kyoto City, it seems that “the mix of residents is completed, so to speak.” While there are many suburban housing complexes in which most residents are elderly people, the downtown area of Kyoto City, where the residents as well as the city landscape continues to be renewed, can be considered an ideal format. How can such a city be preserved for the future? The importance of Yoshida’s research will further increase in the future.

- Tomohiko Yoshida

- Professor, College of Policy Science

- Subject of Research: urban and regional planning, housing policy

- Research Keywords: town planning/ architectural planning