STORY #6

Exploring the Landscape and Spectacles of Kyoto Reflected in Drawings and Old Photographs

Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zu-e, Shijogawara (Collection of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies)

Masahiro Kato

Professor, College of Letters

Finding the footprints of Kyoto’s spatial culturein literary works and drawings to weave a story

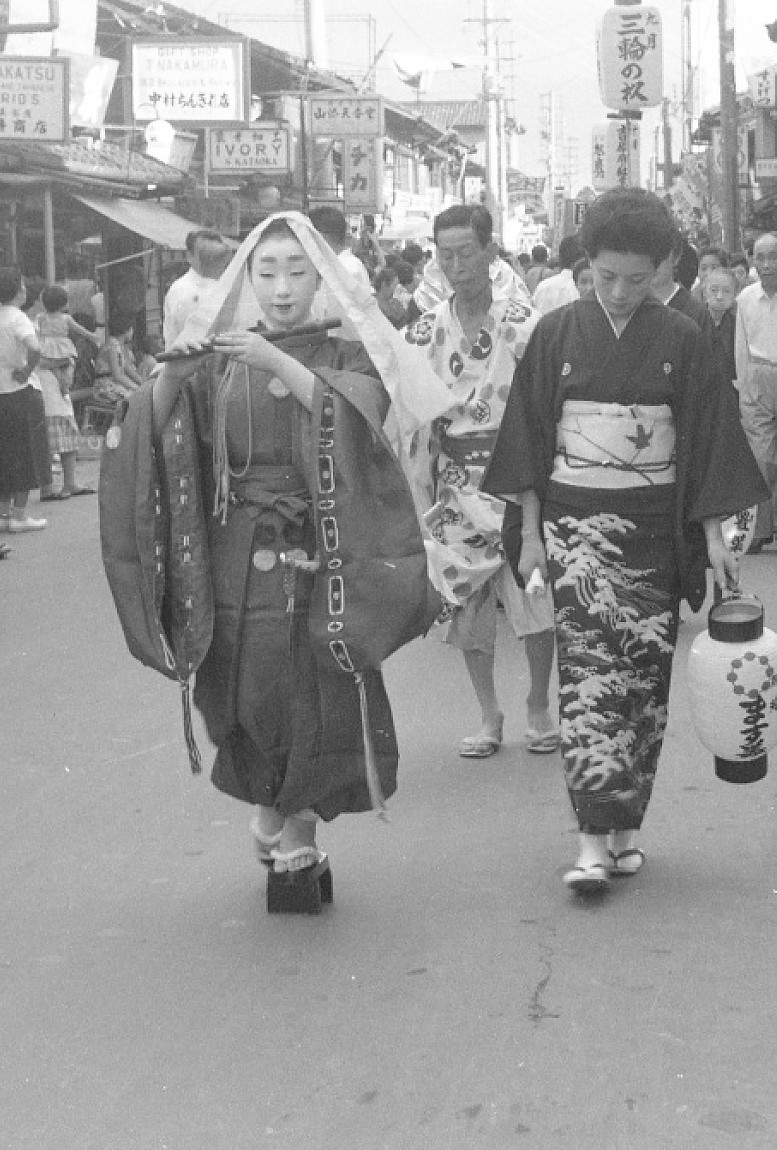

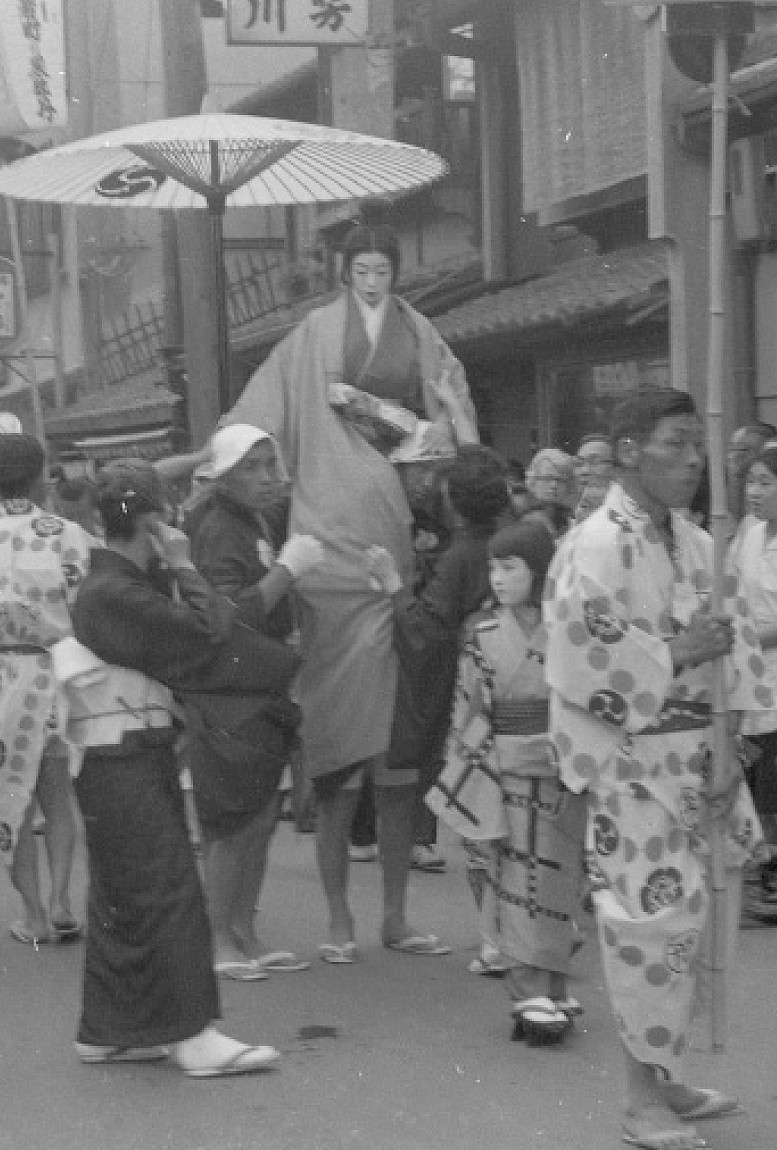

Recently, a large cache of 35-mm film was discovered in a secondhand bookstore. They contained scenery of Kyoto City, including festival scenes, in the Showa 30s (between 1955 and 1964). The photographs were taken by Tokichi Kato, a private researcher of geisha districts which are called Kagai. It was indeed fortunate, both for the film and the photographer, that they happened to be discovered by Masahiro Kato (hereinafter Kato), a researcher investigating the processes of modern city formation via cultural and social geography. Kato had been focusing his attention for a long time on Kagai, which arose naturally in urban areas, and he noticed, among the vast number of negatives, a photograph taken in 1960 that was an image of Nerimono. Kato explained, “During the Gion Festival, Nerimono was an event in which geikos (Kyoto’s local term for geishas) from the Kagai in Gion lined up in a procession to visit the Yasaka Shrine and to parade in and out of the district. Although the form changed after the first half of the 18th century, it continued but intermittently. However, this tradition ended in 1960, which is exactly when this photograph was taken.”

What fired up Kato’s spirit of inquiry was not just the fact that he discovered historically valuable photographs, but also the fact that he found one of the geikos that was captured in a photograph. “My imagination as a researcher was stirred by listening to the living voice of a geiko who had experienced an event that currently is not being carried out.” Kato analyzed the photograph in detail with students interested in his research, and he revealed, “I was surprised that many of the roadside shops and signboards appearing behind the procession still exist exactly as they were.” Continuing with his research, Kato then turned his attention away from the scenery and began instead to develop his interest in the Nerimono itself.

Since the Edo Period, Nerimono continued as a tradition for about 200 years, although it was periodically interrupted and restored. Kato investigated the status of performing the Nerimono and found that its form significantly changed with the times. Initially, it was a celebration, in which geikos visited the shrine, wearing their most elegant clothing, during the night of the Mikoshi arai (purification of a portable shrine with water), one of the rituals of the Gion Festival. However, during the Meiji Era, it developed into an entertainment event, in which geikos marched in a procession dressed similar to what we refer to today as “cosplay.” Furthermore, in 1936 (Showa 11), Nerimono greatly deviated from its conventional form. A concept was introduced to create themes based on the months of the year from January to December using the historical investigations of Kanpo Yoshikawa, who was a historian of manners and customs. Based on that, geikos and maikos wore costumes portraying historical figures matching the monthly themes and walked in a parade. Kato stated, “This would have been a major spectacle in modern Kyoto.”

Apparently, this production was also performed in the last Nerimono in 1960, and the photograph depicts geikos who had dressed up to match the themes of each of the months, such as Momo no Sekku (Peach Festival, also known as Hinamatsuri (doll’s festival)) for March and Gojobashi no Tsuki (the Moon of Gojo Bridge) for August. Kato explained, “So-called traditions have both what was passed down through the generations and innovation. In other words, by means of a constant process of renewal, traditions continue without becoming stuck in an era.”

The last Nerimono of the Showa Period

March: Momo no Sekku (Joro)

April: Nakanomachi no Hanagumo (Sukeroku)

August: Gojobashi no Tsuki (Ushiwakamaru)

September: Miwa no Sugi (Omiwa)

October: Yoshiwara Kuruwa no Momiji (Tayu Takao)

November: Saruwakachou no Kanbotan (Shibaraku)

(Photographed by Tokichi Kato and the property of the Masahiro Kato Laboratory)

Kato also studies Nouryo-Yukas (raised platforms on a riverbank used to enjoy the cool of a summer evening) at the Kamo River as an example of a tradition that changed as it was transmitted to the present. The current Nouryo-Yuka is an event that occurs from early May until the end of September, during which period the restaurants on the western bank of the Kamo River from Nijo to Gojo install raised platforms to be used as sitting rooms along the riverside. Kato and his seminar student have traced the transformation of the Nouryo-Yuka by exploring remnants in literary works, drawings, and old photographs.

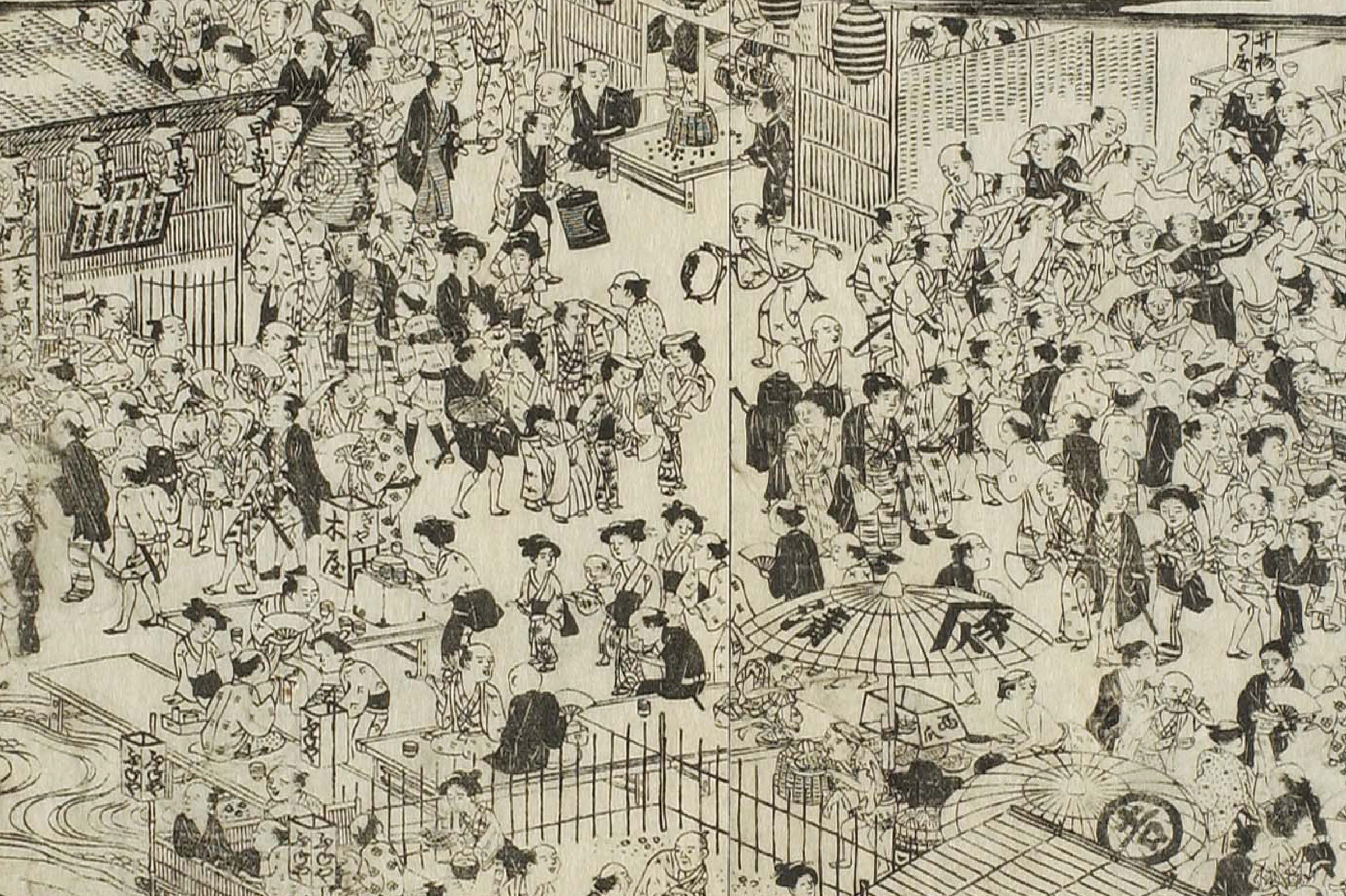

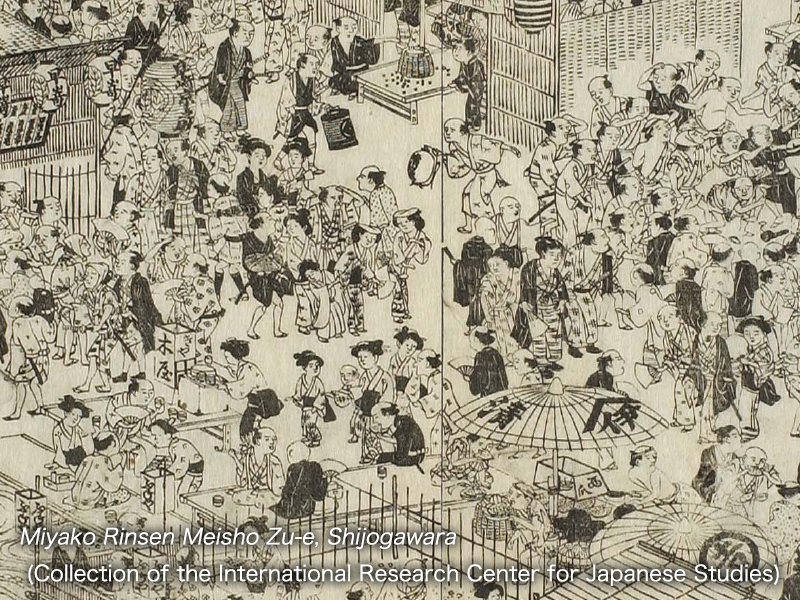

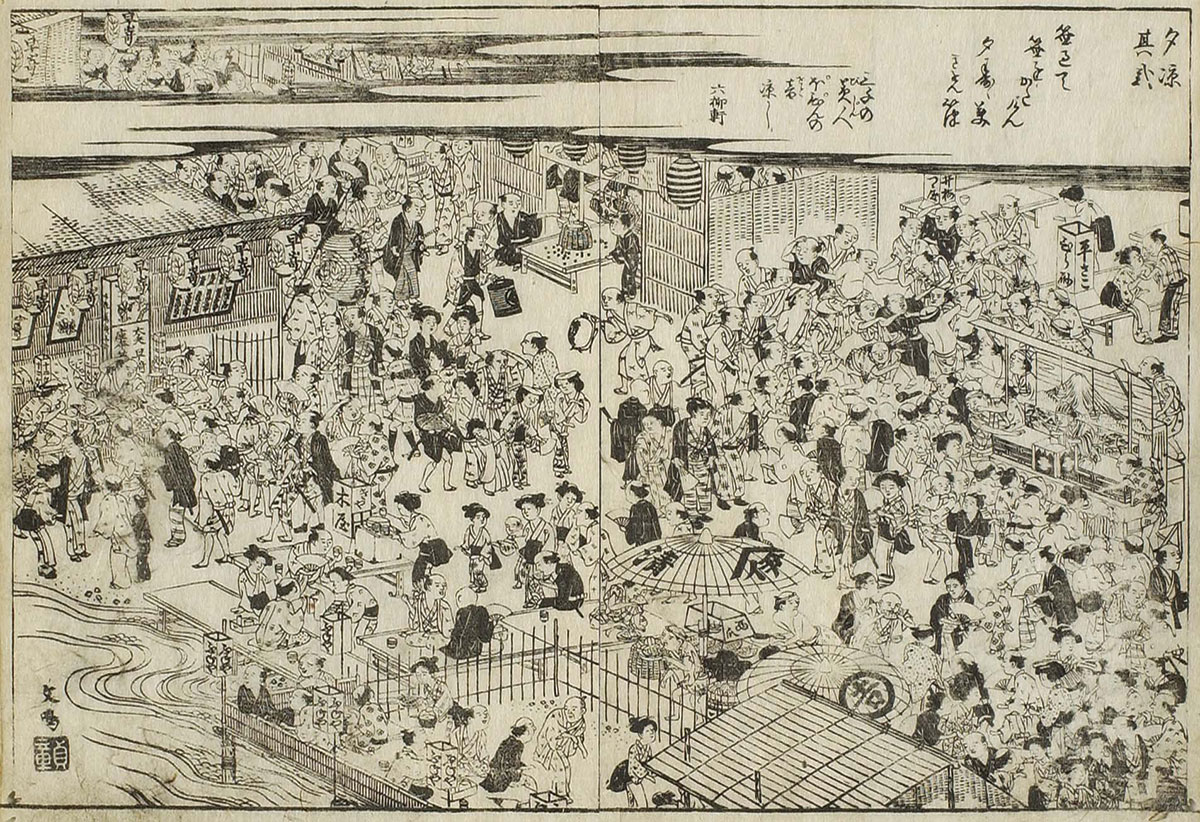

For example, in the Miyako Meisho Zu-e (Images of Famous Places in Kyoto) by Rito Akisato (1780), the picture of people enjoying the cool evening is titled Shijo-Kawara Yusuzumi no Tei (Enjoying the Cool of Evening at Shijo Gawara). Also, in Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zu-e (Illustrated Guide to the Famous Gardens and Sites of Kyoto), published in 1799, two drawings show the theme of cool evenings on the dry riverbed by Shijo. A close examination of these drawings reveals vivid illustrations of men and women of all ages enjoying the summer nights. We can observe an exhibition tent of a troupe of acrobats on the sandbank of the Kamo River (which no longer exists), a man eating a watermelon bought at a stall, men rolling up their sleeves and fighting, and so on. As Kato described it, “You can see from this picture that, during the Edo Period, Kamogawa Nouryo (cool evenings at the Kamo River) was a place rich in pleasures and open to ordinary people.”

Scenery of Kamogawa Nouryo in the Edo Period. People are depicted as enjoying various activities.

The Kamo Rriver appears to have been a place rich in pleasures, which is different from today.

Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zu-e, Shijogawara

(Collection of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies)

According to Kato, when the period changed from Meiji to Taisho, the tradition of enjoying the cool of evenings on the dry riverbed or sandbank disappeared. During the early Showa Period, the main stage of the Kamogawa Nouryo changed to Nouryo Dai (platform stands for enjoying the cool of evening), which are similar to those used today. After the Second World War, Yukas away from the riverbed became common. However, the Nouryo did not revive as a fun activity for ordinary people. Kato pointed out, “When the Nouryo of the Kamo River is understood as part of the spatio-cultural history, it could be said that it underwent a process of gradually losing its original diversity. In other words, it is the history of spatio-cultural impoverishment.”

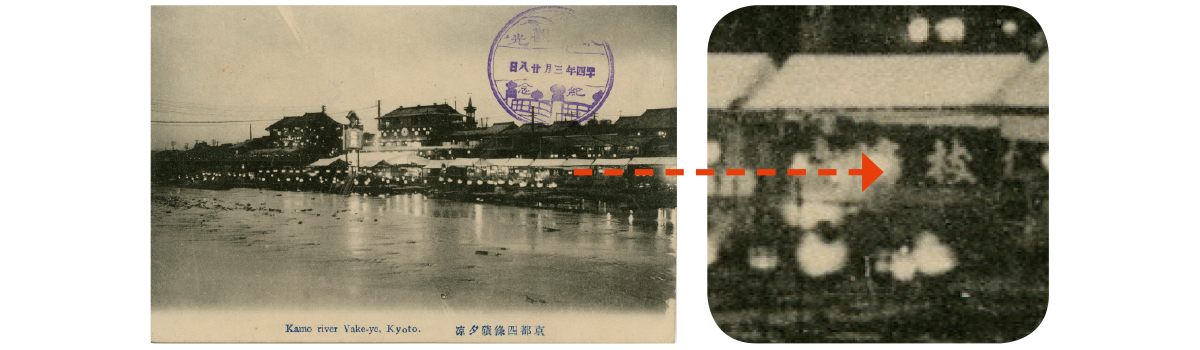

Kato presented a photograph of the western side of the Shijo Bridge in the Meiji Period, which is another piece related to the Kamogawa Nouryo. Written on it are the words Kyoto Shijo Gawara Yusuzumi (cool of the evening on the dry riverbed by Shijo Bridge); and it has been marked by a memorial ink stamp, with the date 1911. Kato and his student, who enlarged the photograph also discovered a shop’s doorway curtain in the photograph, which seems to be printed with the words Mina Tsuki Barae (summer purification rites). This small piece of information has given rise to a new branch of research, since the character Harae (purification) or Barae, depending on the context, “infers a relationship between the Nouryo-Yuka of that time and the Gion Festivals.” Referring to the unfolding nature of his research, Kato enthused, “If I find clues related to the spatial culture of Kyoto in literary works or documents, I feel the need to uncover the hidden story and write about what is there.” Such curiosity underpins his research.

The shop curtains with the character Harae located at the tents lined up on the sandbank under the floor of Ponto-cho (Kyoto Shijo Gawara YuryoYusuzumi, 1911).(The property of the Masahiro Kato Laboratory)

- Masahiro Kato

- Professor, College of Letters

- Subject of Research: study on city-space formation in postwar Japan

- Research Keywords: urban theory, human geography