STORY #1

Digital Archives Preserving Japanese Art and Culture and Making Best Use of It

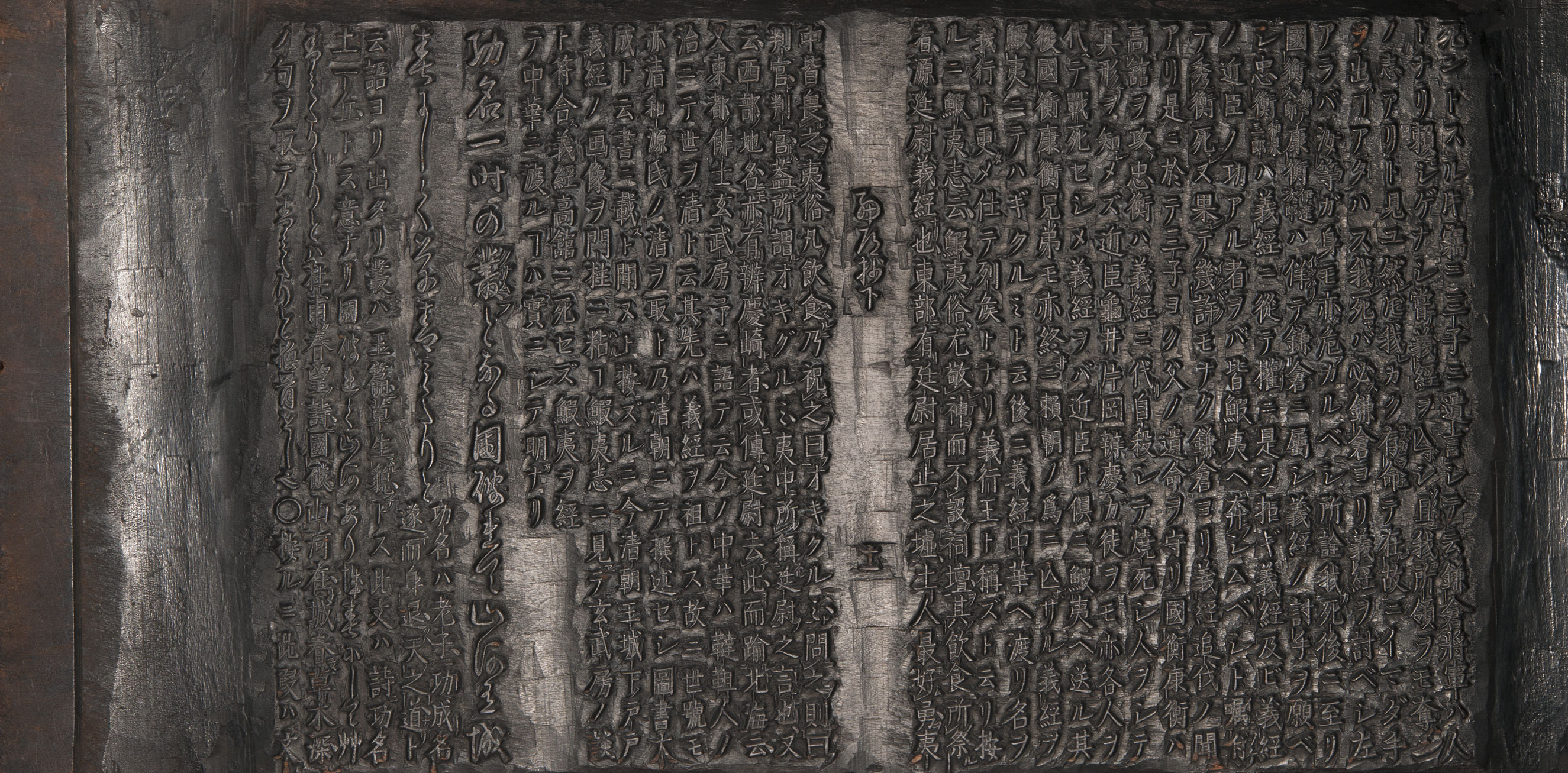

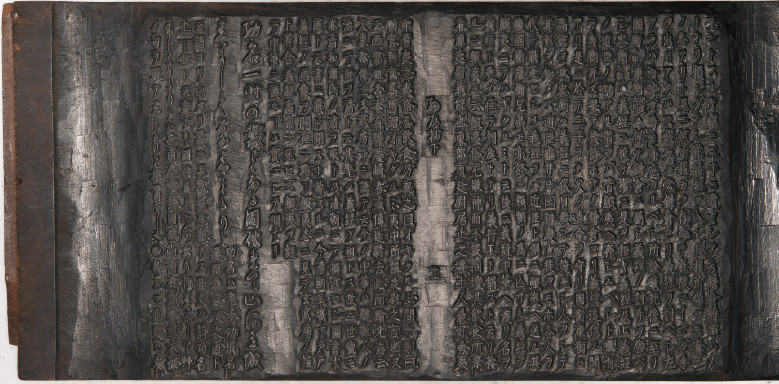

Oku no Hosomichi Sugagomoshō hangi (ARC collection, arcMD01-0714, partial, mirror image); the part posted is from page 11.

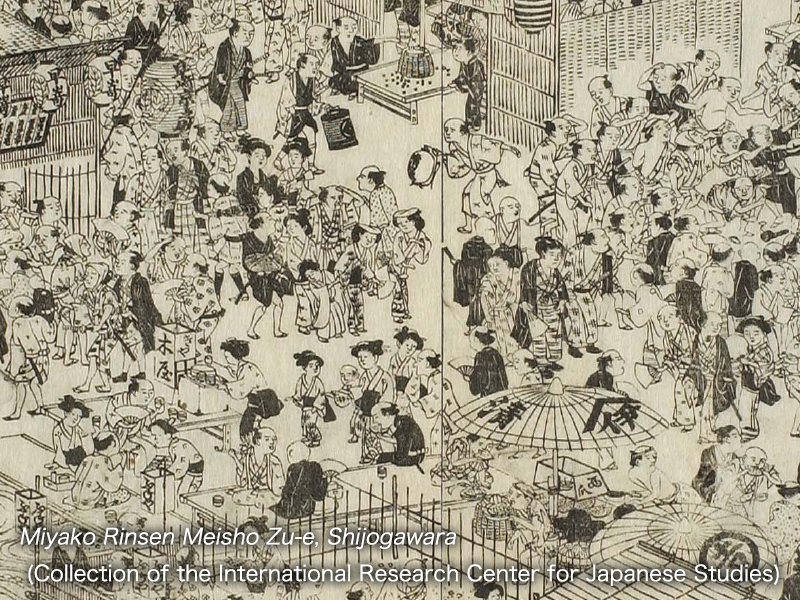

Tracing the footprints of printing blocks to discover the publishing industry of the Edo Period

Takaaki Kaneko

Associate Professor, Kinugasa Research Organization

The invention of printing technology dramatically changed the amount and spread of information transmission. What is known as the oldest printed material in Japan is the 8th century Hyakumantō Darani (“One Million Pagodas and Dharani Prayers”). It is the oldest printed material in the world as an object with a verified production period.

What was mainstream in Japan until the Edo Period was no means of movable types printing but woodblock printing, which consisted of carving letters and illustrations on a wooden block (hangi), put the black ink (sumi) on it, and then placed paper on top of a block, printing it onto paper by rubbing. “Thanks to woodblock printing, which made possible the printing of a large number of repetitions, publishing became commercially viable, and the publishing industry expanded instantly. It can be said that cultural matters in the Edo Period, such as thought, religion, academic studies, and entertainment, as well as literature, could not be described without the hanpon (books printed from woodblocks) made by woodblock printing. The majority of ukiyo-e (prints or painting which reflect the popular culture in the Edo Period) that Japan boasts to the world are multicolor prints using woodblocks.” Takaaki Kaneko, who said this, is an unusual researcher who focuses not only on hanpon itself but also on hangi for printing.

“Hanpon bibliography and study on publishing, which focused on physical ‘things,’ are indispensable for research on early modern art and literature. Nevertheless, there is definitely a lack of information about hangi, which have a prominent part of it,” Kaneko said. One of the reasons is the difficulty in handling hangi materials. They are not widely used for research because the original number of hangi is overwhelmingly lesser compared with hanpon, and there are almost no reproduced materials. Kaneko is trying to solve this problem by using digital archives.

“[Between] Edo (Tokyo) and Kamigata (Osaka and Kyoto), which were the center of the publishing industry during the Edo Period, Kyoto, which escaped fatal damage from earthquakes and wars, is the only one where many hangi still exist. One cannot expect to enhance the archive without the location of Kyoto.” Kaneko, who said this, digitalized about 5,800 hangi materials managed by Nara University as part of an ARC project and released the digital archives on a website.

Lighting is crucial in digitalizing hangi with a surface covered with sumi. After three digitization trials, Kaneko and others adopted a bird’s eye imaging method using a digital single-lens reflex camera. In addition to shooting with flash from the front of the photographic subject, they captured the three-dimensional unevenness of the surface of the hangi from four directions using oblique lighting. They took a total of 20 cut images per hangi. After building an archive of images totaling 90,000 cuts, they are currently promoting the digital preservation of hangi owned by publishing houses that used woodblock printing in Kyoto from the old times, such as Hōzōkan and Unsōdō.

Picture by Toyokuni III, Nijūshi-kō imayō bijin chanoe zuki

(“Twenty-four Enjoyments of Beauties of the Present Day, Fond of Tea Ceremony”)

(1863, ARC collection, arcUP6633)

The same hangi

(ARC collection, arcMD01-0657, mirror image)

“A trace of the thought of publishing houses and craftsmen appear on hangi, from which the existence of the early modern publishing industry has come to be understood to a great extent.” Kaneko discussed the necessity of research on hangi. For example, it has been known for a long time that ireki (wood piece inlay) was put on woodblocks when it was necessary to modify the content of the hanpon. Ireki is a technique of carving out parts of a character that should be modified and incorporating the newly carved piece. Even in the bibliography for hanpon, ireki has long been regarded as a technique for making corrections, but research by Kaneko reveals that this is a misunderstanding. Kaneko said, “It turned out that ireki was not necessarily carried out only for corrections; it was also used in situations such as when there were wood knots on the board and it was difficult to carve it, such knots were removed and replaced with ireki in advance; or in case of difficult characters and kunten (guiding marks for rendering Chinese into Japanese).” Such things cannot be understood only by looking at the hanpon. Facts that overthrow the common knowledge of the bibliography have been revealed by examining the hangi in detail.

ARC possesses the hangi for Oku no Hosomichi Sugagomoshō, which is the oldest one that published as an annotated edition of Oku no Hosomichi (“The Narrow Road to the Interior”) by Matsuo Bashō. Kaneko comprehensively examined this hangi, hanpon, and also the records of publishing, and subsequently revealed the history concerning the publishing, which had not been clarified in previous research, along with facts on commercial publication in the Edo Period.

There are publishing records showing that profits were distributed by the ownership ratio of sharing the hangi, when conducting a joint publication. The hangi used were divided for safekeeping so that the counterpart publisher could not reprint without permission. In another case, hangi was taken as hostage, so to speak, by the holder of the publication rights, so that the book could not be completed without the participation of that person. By following the footprints of hangi, it is possible to see the several-fold information obtained from hanpon, such as the process of printing hanpon, who owned the hangi, to whom the hangi were sold, and how publication rights were transferred. Researchers are extremely few compared with the attractiveness of the research on hangi. Kaneko hopes that “the digital archive of ARC will spread research on hangi.”

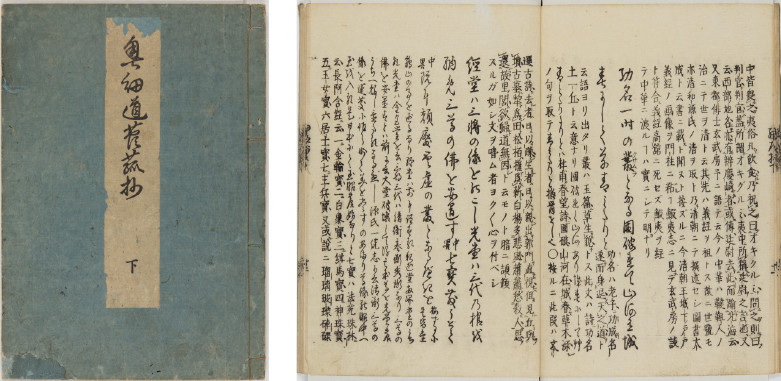

Oku no Hosomichi Sugagomoshō (1778, ARC Collection, arcBK02-0256).

Parts posted are the cover of the last volume, namely, the back-side of page 11 and the front-side of page 12,

the two facing pages of the last volume.

The same hangi (ARC collection, arcMD01-0714, partial, mirror image); the part posted is from page 11.