STORY #1

Protecting historical city from disaster with cultural tradition and life

Takeyuki Okubo

Professor, College of Science and Engineering

Dowon Kim

Associate Professor, Kinugasa Research Organization

Lata Shakya

Visiting Researcher, Institute of Disaster Mitigation for Urban Cultural Heritage, Ritsumeikan University

JSPS Postdoctoral fellow, The University of Tokyo Graduate School of Engineering

A study of disaster mitigation is effective only when the outcomes are implemented into the real society.

On April 25 2015, an earthquake of magnitude 7.8 (Gorkha Earthquake) occurred in mid-western Nepal, with the news stunning the world. Seeing media reports stating that a lot of buildings had collapsed and that a large number of casualties had resulted, Takeyuki Okubo felt frustrated when gathering fragmentary information about the earthquake.

Okubo’s research theme so far is about how to protect cultural heritage and historic city, mainly in Kyoto, from disasters. When he thought to development his knowledge globally, he focused on Nepal, as a World Heritage site. As a part of Education, Research and Development of Strategy on “Disaster Mitigation of Cultural Heritage and Historic Cities” adopted by Ritsumeikan University in 2008, one of the Global COE Programs adopted by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), he began disaster mitigation study in Patan, one of the seven groups of monuments and buildings of Kathmandu Valley World Heritage site. The Global COE Program research resulted in disaster mitigation plans to protect historic townscapes and cultural heritage in Patan from disasters compiled by his team in 2011. He then continued the research, identified disaster-related problems through workshops and disaster drills for local community, and completed a “Disaster Mitigation Map” that shows countermeasures for related issues. The earthquake occurred right when he was about to hand over and feed back this map to local community.

A study of disaster mitigation is effective only when the outcomes are implemented as actual practice to improve actual situations—this is Okubo’s belief. Paying quick attention to Nepal’s risk of disaster, he was disappointed at “missing his responsibility by a second.” However, his study was not in vain; as a result, the earthquake ironically evidenced Okubo’s eight-year research achievements.

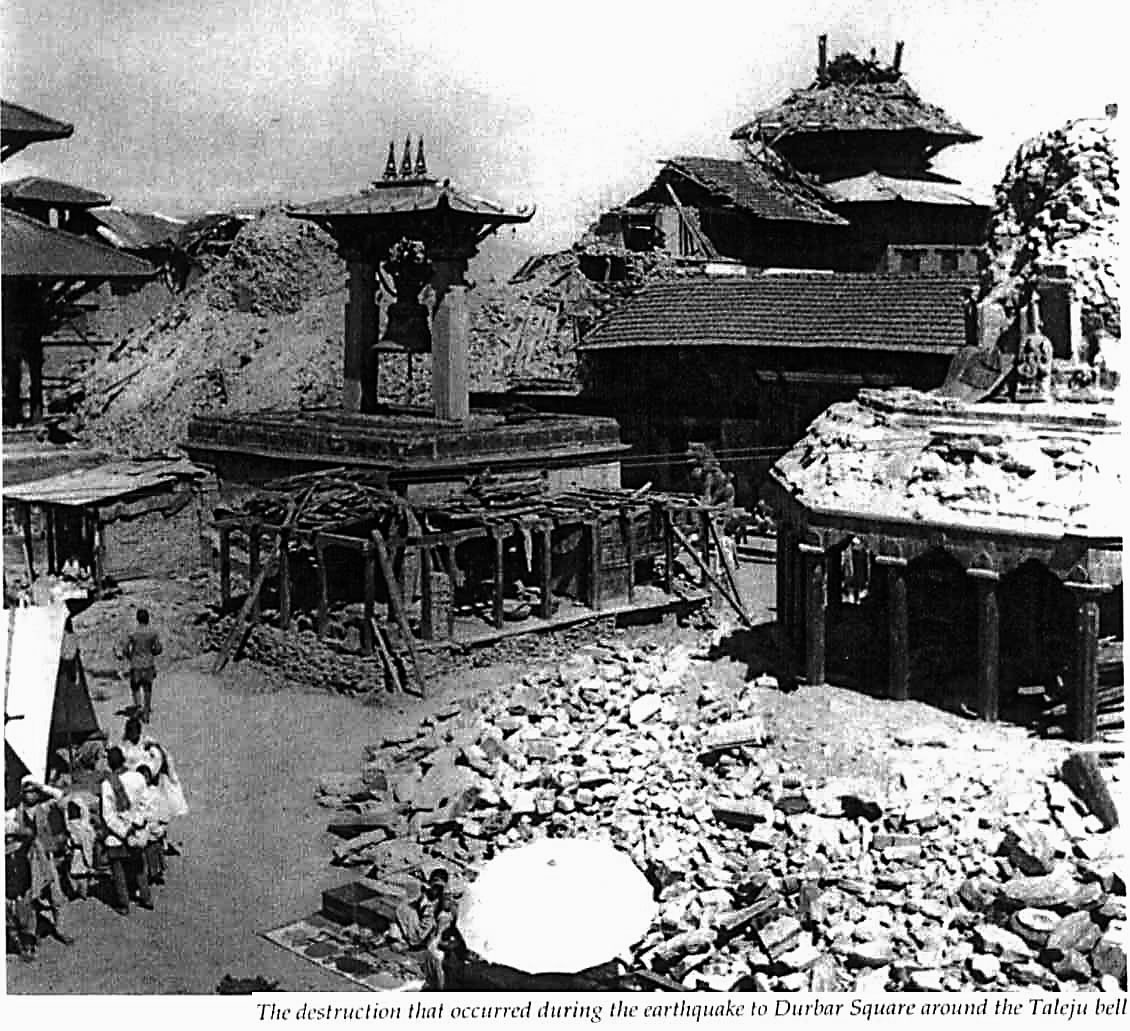

Mangal Bazar (former) in the Patan region, destroyed by the earthquake in 1934

Reference: The Bihar-Nepal Earthquake of 1934, Geological Survey of India, Calcutta, 1981

Durbar Square in the Patan region, which suffered from the Gorkha Earthquake; brick walls came tumbling down, exposing the wooden frames. Emergency responses for aftershocks were taken.

How is society to protect the cultural heritage sites that human civilization has constructed throughout history? Amid the backdrop of increased global disaster occurrence, to protect cultural property is an important challenge. In relation, Okubo puts emphasis on protecting not only historical townscapes and buildings as cultural assets, but also the traditional life, business, and culture on which cultural assets are based. “Townscapes and buildings are the representation of human’s traditional lives and cultures. If all of these are not protected, a building is just an empty box however rare it is,” Okubo says.

Nepal, located on the boundary of the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate, has a high concentration of active faults, which makes Nepal a country with extremely high risk of earthquakes, similar to Japan. According to Okubo, records indicate that the last big earthquake was in 1934 and was of magnitude 8.4, killing over 8,500 people and completely destroying more than 80,000 buildings. Kathmandu, the capital, has also lost historical and cultural buildings due to earthquakes. Recently, the Nepalese government has been paying attention to the protection of cultural heritage, but “It’s not enough,” Okubo points out.

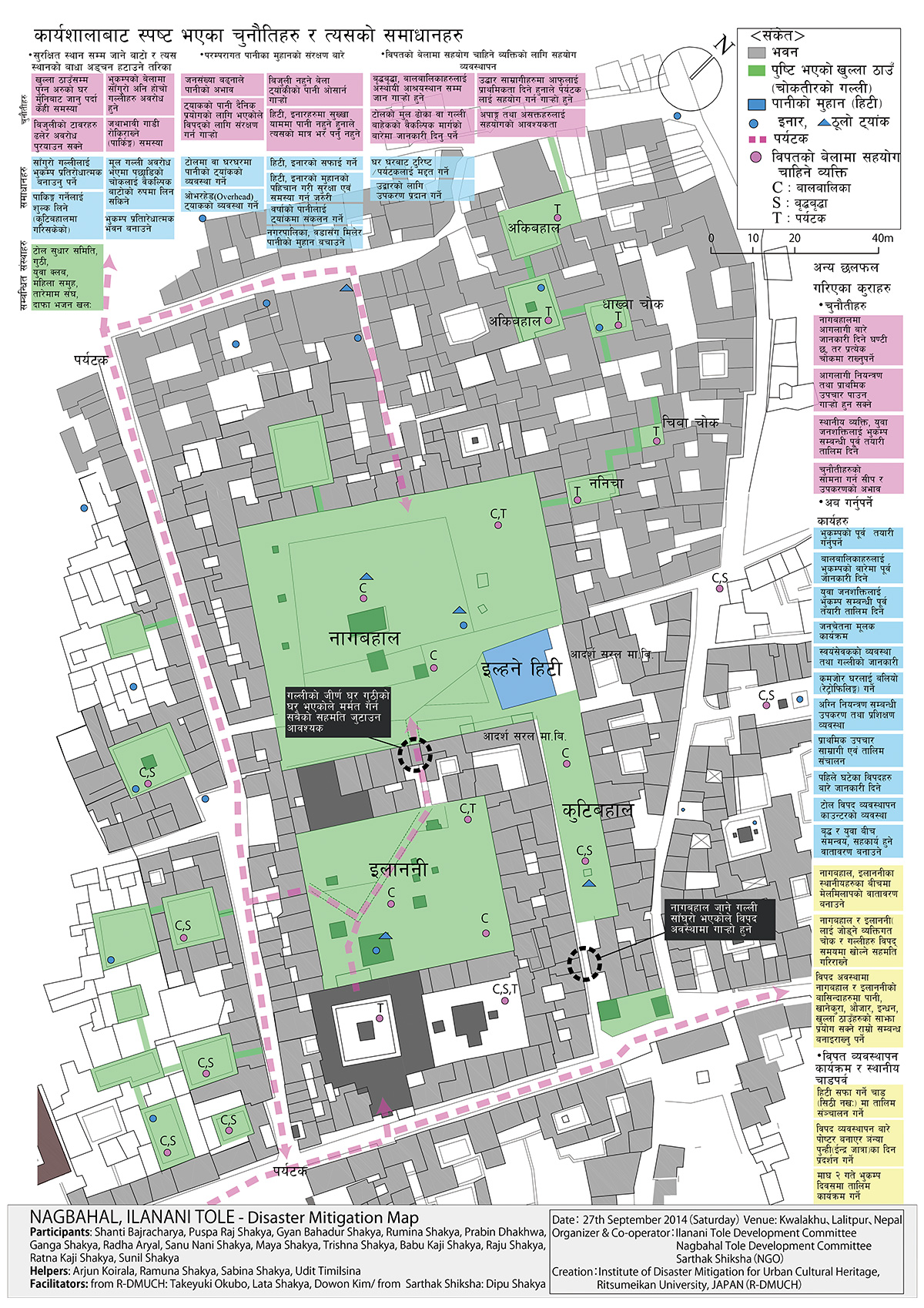

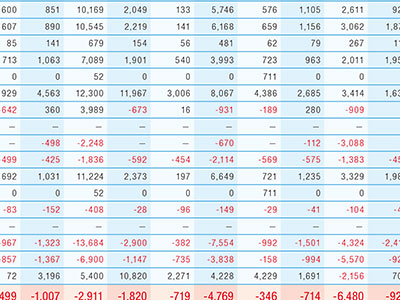

[Ilanani, Nagbahal District Disaster Mitigation Map]

A disaster mitigation map (September 2014) devised from the information gained through repeated workshops with local people, as an application for a district disaster mitigation plan drafted in 2012; this covers detailed items, including the identification of all the problems assumed to occur during a disaster, a review of traditional disaster mitigation situations, and daily countermeasures. This is the disaster mitigation map designed by local people and used by local people. From now on, the researchers are planning to disseminate information through workshops with local people, etc.

In the research of the Global COE Program, Okubo organized a team that included professors of local universities, and set out to analyze structures, conduct social surveys in regional communities, and assess earthquake risk, focusing on historical buildings that are used for residences even today. First, he focused on Patan, Nepal’s third largest city, located in the southwest of the Kathmandu valley.

The historical townscape of Patan features a building style known as “facing to courtyard” style. The district that Okubo surveyed consists of about 90 tightly-dense buildings and many courtyards as semi-public living spaces, which are linked with each other by narrow paths that connect to main streets. Element analysis revealed that most of the buildings are not only fragile three-story buildings simply made of bricks, but that, in modern period, extended stories have also been added on top. As a result, the buildings were in a dangerous state due to excessive weight being shouldered, even in non-disaster times. If an earthquake affected such buildings, rubble would immediately block the narrow paths, interrupting escape to the outside and interrupting rescue within the district.

Although the structure of this city, based on traditional life and culture, has high historical and cultural value, aseismic reinforcement using modern technology is not always the best measure, due to aspects regarding the protection of rare historical heritage and due to cost. In addition, Okubo considers that “The buildings cannot be protected without the effort of residents. It’s important to carefully work out disaster mitigation plans that consist of both building reinforcement and an improvement of the mindsets of the local community involved regarding disasters.”